Vimy (30 page)

Authors: Pierre Berton

All in all, the reserve troops who fought the final stages of the 1st Division’s battle had had an easier task than the first wave that jumped off at Zero Hour. In spite of the threat to its flank, the 2nd Battalion, being in reserve, lost only 108 men killed, wounded or missing. By contrast, the 7th from British Columbia, which was in the vanguard of the forward brigades, lost 364-more than three times as many. And yet in the neighbouring 2nd Division, the opposite proved true. There it was the reserve battalions that suffered most, the leading waves that escaped. War, like life, is as random as a roulette wheel.

CHAPTER ELEVEN

The 2nd Division

1

On the 2nd Division front that dawn- to the immediate left of the 1st-William Pecover had a ringside view of the opening stages of the battle. His battalion was in reserve; it wouldn’t go over the top until nine o’clock. Standing in the trenches with the other Winnipeggers, Pecover watched the forward elements of his division – the Ontario regiments, the New Brunswickers, and the Victoria Rifles from Montreal – launch the attack.

In front of him the sea of mud seemed to stir into life. Out of the maze of dark shell holes and bits of jumping-off trenches, thousands of khaki-clad figures suddenly emerged, some leaping, some crawling in the mud, some stumbling and lurching forward against a lurid background of flame from the belching guns. Pecover could not contain his awe at the spectacle unfolding before him: the desert of No Man’s Land lit by the stark flashes of red; the wet, grey dawn beginning to streak across the sky; and, later, the lines of prisoners stumbling back toward him, a scattered few at first, then greater and greater numbers. How, he wondered, could they have survived? It seemed that no inch of ground held by the enemy could have escaped that rain of death.

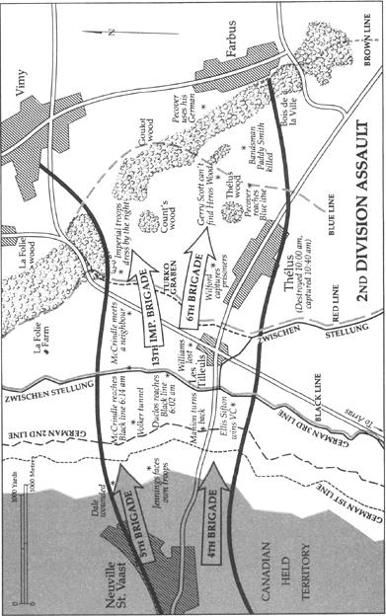

Unlike the 1st Division, the 2nd had only two miles to go to reach its final objective, the belt of woods that ran for a mile and a quarter along the base of the ridge on the German side, concealing more of their guns and reserves.

If the momentum of the attack could be maintained, the division would roll over what was left of the hamlet of Les Tilleuls and the ruins of Thélus, from whose cellars and dugouts on the ridge’s crest the Germans were harassing the attackers. Then, at the half-way point, fresh troops would sweep down the far side of the escarpment, through the stumps of Thélus Wood and Heros Wood to reach the gun positions hidden in the long forested belt at the base-the Brown Line on the maps.

Tactical and logistical considerations dictated the strange wedge shapes of the two divisional sections. The 2nd Division’s front was narrow at the outset-about half a mile wide, or less than a third of the breadth of the 1st Division’s front. It conformed almost exactly to the contours of Neuville St. Vaast, directly in the rear, from whose caves and subways the attackers would emerge. But, unlike the 1st Division’s attacking sector, which narrowed as it reached the ridge, that of the 2nd Division broadened out to a mile and a quarter at the Brown Line, to conform to the shape of the slender belt of trees-Bois de la Ville and Goulot Wood-that ran between the captured villages of Farbus and Vimy flanking the divisional boundaries.

Obviously, an extra brigade would be needed at the halfway point-the Red Line near Les Tilleuls- to fill the widening gap. The additional troops would be British – supplied from the 5th Imperial Division, now seconded to the Corps reserve.

As Pecover watched and waited for his turn, he could see that a weird kind of shuffle was taking place up ahead. Into the ghastly limbo of exploding debris, the clumps of attacking Canadians advanced and vanished. Out of it, moments later, straggled other clumps of men-endless groups of shaken Germans.

One of the first Canadians into the maelstrom was a young New Bruns wicker, Charles Norman Dale. He stumbled forward behind his sergeant with two others filing after him. None made the German line. Almost immediately a shell hit the ground two yards away, buried itself four feet in the mud, and exploded, knocking Dale off his feet and breaking his right leg at the top of the thigh. Dale stuck his rifle in the ground, shucked off his equipment, crawled to a dugout, and waited more than six hours before a German prisoner came along and carried him to a dressing station. It was his first time in action – and his last.

As Private Dale slumped into the mud, an unforeseen problem arose at the mouth of the sap that Duncan Macintyre had discovered leading into the Phillips Crater in the heart of the battlefield. Macintyre had his signals crew installing telephone lines and rolls of surface cable in the sap ready to jump out of the crater and keep up contact with the rear as the assault rolled forward. Now, as the attack began, the Divisional Signals Officer, Major D.C. Jennings, climbed to the surface facing his own lines only to see his own troops advancing upon him, hurling grenades. As far as they were concerned, anyone that far forward had to be a German. Jennings popped quickly back into shelter. After the first wave passed over their hideaway, the Pioneer section sprang out and began to dig a six-foot trench to hold the cable while the signallers, moving right behind the advancing troops, unrolled the telephone wire.

Meanwhile, Andrew McCrindle, the baby-faced nineteen-year-old with the reserve platoon, Victoria Rifles, waited his turn to go over the top. Already McCrindle could see men falling-not in the dramatic way they did in illustrations or in the silent films of the day, flinging their hands in the air or clutching their hearts before toppling forward; here on the slopes of Vimy they just seemed to sink disconsolately into the earth. The dead did not distress McCrindle as much as the wounded who were left groaning and bleeding in the mud without help while the battle swept on past.

Almost as soon as McCrindle went over the top he fell into a shell hole, up to his knees in mud and water. He felt like crying: there he was, floundering helplessly in the muck while everybody else shuffled past him. At that moment another youngster spotted him, leaned over, and with his rifle pulled McCrindle out. The smell of cordite was strong in his nostrils as he hurried to catch up. Shells were bursting all around him; but it seemed to Andrew McCrindle that some good fairy had equipped him with an invisible shield, for while others fell, he survived.

A machine gun opened up on the left. McCrindle’s platoon sergeant deployed his men, just as in training, to attack from three sides with rifle grenades. One lone German survived the tactic; they sent him back on his own to the Canadian lines.

Ahead lay the great Volker Tunnel, too deep within the ridge to be damaged by the Canadian artillery. It was packed with Germans armed with machine guns, waiting for the first waves to go by before attacking the second waves from the rear. But McCrindle’s company didn’t stop-the task of clearing the tunnel would be left for others. Up ahead they spotted a German officer leading a group of men, firing his pistol directly at them. One of McCrindle’s platoon mates, Arthur Abbey, rushed at him, knocked him down, took his pistol, forced the others to surrender and, for that deed, won the Distinguished Conduct Medal.

The objective lay dead ahead. Not far away the troops could see the captain of a neighbouring company, V.E. Duclos, turning about and throwing open his overcoat so that the men of his company could spot the white lining and keep their alignment. Duclos was already wounded but kept going until his men had punched their way through the enemy’s forward defences to reach the Zwischen Stellung trench. This was the Black Line. Duclos’s men reached it at exactly 6:02, ahead of schedule. McCrindle’s company arrived twelve minutes later. Behind them a furious fight was taking place for the Volker Tunnel, which had been mined. Fortunately, the Canadians discovered the trap in time and cut the leads before they were all blown up. At 6:25 the soldiers, digging in, heard the sound of a klaxon above them as a British biplane swept past to see by the flag signals that the objective had been reached.

In this first advance, the casualties had been remarkably low. Again the fury of the barrage had unnerved and surprised the Germans. McCrindle and his section rounded up one astonished officer still in his pyjamas. Piqued at having to surrender to mere private soldiers, he vainly demanded the presence of an officer. McCrindle stole his epaulettes as a souvenir and hustled him back to the Canadian lines.

Over on the right, Sergeant Ellis Sifton’s platoon was digging in with their fellow units, all from Ontario. During the advance Sifton had performed an act of conspicuous gallantry, hurling himself at a machine gun that was mowing down his men, charging directly at its crew, clubbing some with his rifle and slashing at others with his bayonet. He didn’t know it, but that act would win him the Victoria Cross. Nor would he ever know it. As he supervised the capture of the prisoners, a wounded German managed to reach for his rifle, point it at the sergeant, and squeeze the trigger. Sifton was dead before he hit the ground.

The enemy casualties were catastrophic. Entire battalions were wiped out. One of the battalions of the 79th Reserve Division, directly across from the Canadian 2nd, was so badly cut up that only one man escaped. This was Musketeer Hagemann, a quiet and sober farmer from the Lüneburg area of Germany. At first, Hagemann’s battalion held fast and Hagemann was reassured to see rows of the Canadian attackers felled by his machine gunners on the flanks. But the German artillery proved useless, firing over the heads of the Canadians and falling on empty areas in the rear. On the other hand, Hagemann noted, the Canadians directed their own artillery to points of resistance by means of Very light signals from their aircraft. Soon men began to topple all around him. The machine gun next to him, which had created such devastation, was put out of action, the entire crew dead. As the Canadians committed fresh troops to the attack, the Germans moved back from crater to crater, dying and bleeding as they retreated. It seemed to the stolid Hagemann that there wasn’t anybody left on his side who wasn’t hit. He himself was bleeding from three wounds. His right arm was paralysed. He could fight no longer and so fell back, the only man in his entire battalion to reach safety.

2

On the 2nd Division’s Black Line, the troops were being shuffled, the rear waves moving forward to take over from the leading waves in order to continue the next stage of the assault, following the creeping barrage to another great German trench known as the Turko Graben, just below the crest of the ridge. This was the Red Line; some of the troops would have to travel a mile to reach it. But the German resistance continued to crumble, and in a little less than half an hour the Turko Graben was in Canadian hands. Here, in a large shell hole, the troops were treated to a sight that might have been affecting had it not seemed so ludicrous: a dozen Germans, every man jack of them on his knees praying.

The Germans, meanwhile, were shelling the ground just ahead of the Canadian trenches, long since vacated by all but the staff officers moving their battle headquarters forward over captured territory.

Stranded in No Man’s Land, half-way between the old Canadian front and the Zwischen Stellung trench, Captain Robert Manion, the future politician, thought his last hour had come: his wife, back in Ottawa, would receive his pocket diary, but she would never know the details of how he, the Medical Officer of the 21st, had met his end, huddled in a trench with shells exploding all about him, a wounded colonel clinging to him and a padre on his knees beside him.

For that was all that was left of the thirty officers and men who had set out that morning at 7:30 to establish a forward headquarters in the captured Zwischen Stellung trench. Shrapnel had sent all but this trio scuttling back to safety, and now the colonel was bleeding from wounds in the arm and the leg.

To Manion it made more sense to go forward than back. It wasn’t easy. His wounded C.O. stumbled and fell to his waist in the mud. Manion pulled him clear. As they blundered forward again, the wounded man toppled into a shell hole. Clearly he couldn’t go on; they would have to turn back. Manion tried to carry the C.O. When that didn’t work, he dragged him for 250 yards to the shelter of another shell hole. They threw away their equipment and began crawling from hole to hole in a zigzag pattern toward their own lines. Miraculously, they made it.

Captain Manion, who won a Military Cross for his efforts, finally reached the Zwischen Stellung by another route, passing on his way a group of tanks bogged down in the mud. They were supposed to support the advance of the division in its attack on Thélus, but they hadn’t even reached the Black Line. The mud was too thick, the shell holes too deep, the ground too treacherous, and the High Command too uncertain that these devices should be used. They looked awesome enough with their great snouts heaving over the lips of the craters, their engines snorting, and their treads rattling. But now, as Manion passed them, all were immobilized.

Up ahead, on the Red Line-the Turko Graben-the barrage lifted and came down on the German positions two hundred yards farther on. The troops dug in, the moppers-up did their work, and fresh units of the 6th Brigade – “The Iron Sixth” – held in reserve until this moment, moved out of their positions and prepared to push through to the next objective.