Vimy (9 page)

Authors: Pierre Berton

BOOK TWO

The Build-Up

What I want is the discipline of a well-trained pack of hounds. You find your own holes through the hedges. I’m not going to tell you where they are. But never lose sight of your objective. Reach it in your own way.

Lieutenant-General Sir Julian Byng to his officers,

Vimy sector, 1917

CHAPTER THREE

Marking Time

1

By mid-November 1916, the Somme offensive had petered out and the British Army in northern France, shivering in the coldest winter in half a century, was marking time. The shattered battalions of the Canadian 4th Division, which had fought so hard to capture the Regina Trench, had moved north to join their compatriots. By December, the exhausted Corps was united again, strung out thinly for ten miles along the Artois sector between Arras to the south and Loos to the north.

Change was in the wind. The French commander, Joffre, had been cast aside in favour of the more aggressive Nivelle. The vigorous Welshman, David Lloyd George, had replaced the lethargic Herbert Asquith as Prime Minister of Great Britain. In spite of Haig’s doubts, these new and powerful personalities were determined to transform the war of attrition into a decisive war of movement. But before the great breakthrough could be achieved, one obstacle had to be eliminated. The Vimy bastion must be captured and held.

Tactically, the ridge was one of the most important features on the Western Front, the anchor point for the new defence system that the Germans were carefully and secretly preparing to thwart the expected Allied hammer-blow.

There it lay, facing the Canadian lines-a low, seven-mile escarpment of sullen grey, rising softly from the plain below, a monotonous spine of mud, churned into a froth by shellfire, devoid of grass or foliage, lacking in colour or detail, every inch of its slippery surface pitted or pulverized by two years of constant pounding. At first glance it didn’t seem very imposing, but to those who knew its history and who looked ahead to that moment when they must plough forward and upward toward that ragged crest aflame with gunfire, it took on an aura both dark and sinister.

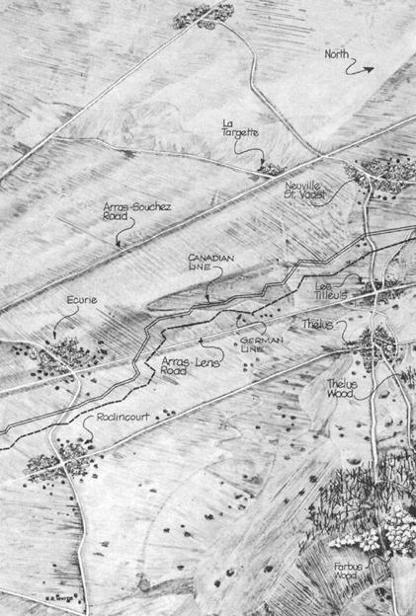

The high crest of the ridge-the part that counted tactically-lay between two river valleys, the Souchez to the north and the Scarpe four miles to the south. This would be the Canadian objective, but that wasn’t yet clear in December and wouldn’t be until early February, when the entire corps was squeezed into this four-mile sector. The ground between was shaped like a great pie section because the Canadian lines didn’t parallel the ridge but veered away from it at an angle. At the southern boundary, the Canadians were four thousand yards from the crest, at the north, a mere seven hundred. Between lay No Man’s Land, a spectral world of shell holes and old bones. Down its midriff a ragged line of gigantic craters marked the sites of earlier mine explosions in the failed struggles to capture the ridge. Some were so vast that Canadian sentries and snipers held one lip while the Germans squatted on the opposite rim.

Beyond the crater line-in places no more than a few dozen yards away-three parallel rows of German trenches zigzagged along the lower slopes of the ridge, protected by forty-foot rolls of heavy steel wire with razor-sharp barbs and machine-gun nests in steel and concrete pillboxes.

Behind these forward defences rose the dark bulk of the escarpment, which more than one new arrival likened to that of a gigantic whale. Its highest point, Hill 145, rose 470 feet above the plain to form the mammal’s hump. A mile to the north, on the edge of the Canadian sector, was a small knoll, poking up like a pimple on the whale’s snout and called, naturally enough, the Pimple.

A mile south of Hill 145 was another hill near whose slopes was sprawled a farm that was no longer a farm – La Folie. Two miles south of that, straddling the crest near the right of the corps boundary, was a village that was no longer a village-Thélus. Directly in front of these ruins, high on the forward slope, stood the fragments of Les Tilleuls (the Linden Trees), a hamlet that was no longer a hamlet, clustered in a grove that was no longer a grove. These dead communities added to the starkness of the scene and hinted at the intensity of the struggles that had gone before. Veined by trenches, honeycombed with tunnels, bristling with gun emplacements, crawling with snipers, this formidable rampart had been in German hands since October 1914. The Germans intended it to stay that way.

From their vantage points on the crest, they had an uninterrupted view for miles in every direction. Behind them, among the forests that still cloaked the steeper eastern slopes and hid their big guns, lay small, red-roofed villages not yet entirely shattered by shellfire: Givenchy-en-Gohelle, in the shadow of the Pimple, Vimy and Petit Vimy directly to the east, and, to the south, the village of Farbus, sheltered by Farbus Wood. Far to the rear lay the spires and slag heaps of Lens, the heart of France’s coal mining region, now denied to the Allies. Here was life, movement, and colour: carts and lorries clattering along the Lens-Arras road, freight trains snorting past on a rail line that once was French, peasants toiling in the fields, troops moving about in broad daylight, smoke pouring from the big stacks at Lens- and all this spectacle shielded from the soldiers of the King, observable only by a handful of brave men in captive balloons and by the young knights of the Royal Flying Corps.

To the west, the Germans looked down on a dead world, stretching back for more than six miles, in striking contrast to the scene behind. Back of the line of craters they could see the blurred contours of the Canadian forward trenches and behind these two more lines-the support and reserve trenches. Farther back, parallel with the trench lines, were three deeply sunk roads, and beyond these the Arras-Souchez highway.

Bisecting this lifeless, underground domain were the great communication trenches, which sheltered the troops moving up to the front at night; one was four miles long. For nothing moved above ground by day, and even the nights were hazardous, especially when the German flares banished the covering gloom. The swampy Zouave Valley on the northern edge of the Canadian sector was a hunting ground for German snipers and gunners. The Canadians called it Death Valley; every man who crossed it did so in full view of the enemy. There were trenches there, too, but these were generally so full of liquid mud that many preferred to chance a quick nocturnal dash above ground. That was a court-martial offence, but many accepted it: anything-an enemy bullet, an army trial – was better than strangling in a river of running slime.

The Canadians had one advantage. The German defences on the forward slopes of the ridge were also exposed, and the time would come when the Canadian guns would blast them into rubble. But for the moment the Germans had the upper hand. For six and a half miles, every piece of Canadian equipment, every gun, every ammunition dump, every lorry pool, every ration depot-everything that could be blown apart or could give the Germans some inkling of what was to come-had to be concealed in pits or camouflaged or hidden behind folds of ground or copses of foliage.

The safest places of all were the big subways that went as far back as Neuville St. Vaast and as far forward as the front lines. The Germans knew they were there but had no clear idea of what was going on below ground. The presence of those subways – a dozen of them – some nosing forward inch by inch, foot by foot, dozens of feet below the surface, was the hole card in the game of poker being played out that winter in the shadow of the ridge.

In this ravaged world, the French villages were little more than heaps of rubble. Arras, three miles to the south, which would give its name to the great spring offensive of which the Vimy attack was a part, was a shell. Restaurants, stores, cafés were battered to bits; the cathedral was a wreck, the railway station a ruin. Ecurie, on the southern border of the Canadian sector, once a haven for French farmers, was no more than a name on a signpost, a flattened expanse of brick dust, bisected by roads that could be used only at night. Neuville St. Vaast, once the White City of Flanders, was a desert of rubbled chalk, its inhabitants long since fled. Someone had erected a bitter sign: THIS

WAS

NEUVILLE ST. VAAST. Only in the cellars, tunnels, and caves below the surface, which concealed railway terminals, gun positions, and troop facilities, did life go on. The town cemetery was devastated, every monument knocked down, the vaults smashed, the coffins shattered. Beneath the broken trees, skeletons of Frenchmen long gone lay contorted among the clumps of rank grass.

Souchez and its neighbour, Carency, had been blown away to their foundations by the dreadful struggle of 1915. One foggy morning Bob Brown, a Scottish immigrant from Regina, explored the ruins of Souchez with two others. The town was out of bounds, and Brown was curious to know why. He soon found out: Souchez was a human abattoir. Skeletons lay everywhere. At one point he found a spot where a Frenchman had been standing, rifle in hand, at the moment a building was hit. The man’s skeleton, still clutching the rifle, lay under a heavy beam. A trench dug across the main street and filled with skeletons had yet to be covered over. But the most affecting symbol was the schoolhouse, its roof gone, its walls blown in, but the teacher’s desk still standing with the roll book marking the day the school had been forced to close. Brown tore out the page, pocketed it, and left Souchez to its ghouls and ghosts.

The ridge and its environs stank of death, and the trenches were sour with it. One of the first things that hit the newly arrived Canadians was the evidence of old and monumental struggles. At the ridge’s northern end, above the Souchez River, a promontory named for the Abbey of Notre Dame de Lorette butted out at right angles. Here the French had managed at fearful cost to wrest the plateau from the Germans, and the evidence of that struggle for what they then called La Butte de la Mort (the Hill of Death) was everywhere. When Will Bird, with his sensitive writer’s perception, first saw the carnage on the Lorette Spur, it made his flesh crawl: he had never before seen so many grinning skulls. Here was a maze of old trenches and ditches littered with the garbage of war-broken rifles, frayed equipment, rusting bayonets, hundreds of bombs, tangles of barbed wire, puddles of filth, and everywhere rotting uniforms, some French blue, others German grey, tattered sacks now, holding their own consignments of bones.

Farther south lay the Labyrinth, another city of the dead, a bewildering network of caves, tunnels, trenches, and dugouts, circulating and radiating in all directions. Here again French and Germans burrowing beneath the ground had blown each other up and fought hand to hand with knives and clubs. French equipment, human bones, wire, and scores of homemade bombs-jam tins filled with scrap-iron, nails, and stones-lay everywhere. In the Aux Ruitz cave, it was said, there were so many dead that one tunnel had to be walled up.

Through this tangle of decaying artifacts the souvenir hunters picked their way, insensible to the heart-breaking evidence of human waste. As Private Donald Fraser, a six-foot Scot from Calgary, confided to his journal, “rifling the dead used to be considered in pre-war times a ghoulish business but over here the dead are of no account, they are scattered all over the battle area.” An inveterate collector, Fraser spent many of his spare hours cutting the buttons off the tunics of corpses.

There were subtler hints, however, of those earlier battles, certain nocturnal sounds-mere whispers between the crump of the guns – that could send a shiver up the spine of those who had been hardened by a long acquaintance with the dead. In the French cemetery at Villers-au-Bois, thousands of temporary crosses marked the resting places of those bodies that had been awarded a formal burial. On each of these crosses, the French had placed a small tri-coloured metal triangle as makeshift identification. In the night, when a chill breeze sighed through this city of the dead, the men in the trenches could hear the eerie clink-clink-clink of these thousands of tin triangles, a reminder of the vast and ghostly army that had preceded them.