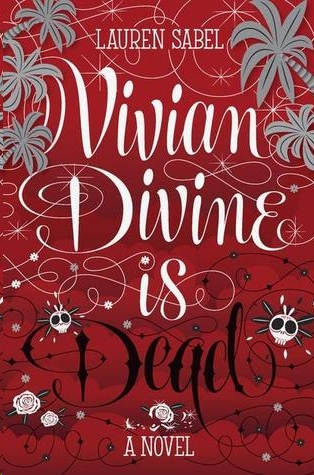

Vivian Divine Is Dead

Read Vivian Divine Is Dead Online

Authors: Lauren Sabel

To my husband, my sword, and my family, my shield

Contents

M

Y NAME IS

V

IVIAN

D

IVINE

. I have a secret. I know how I’m going to die.

No one would believe me if I told them. Not that I would. Or could. Someone’s always watching. Sometimes I see the tip of a gray head in my window, or an eye behind a fish tank. They’re always there: a silver sedan pulling out of my driveway, a glimmer of gold in a dark room.

My dad says he doesn’t see anything. I know he doesn’t. He doesn’t see me.

Since my mother died six months ago, he’s lost himself in his work. Now the only time I see him is behind a camera. He’s the most famous director in Hollywood, and that means he’s busy all the time—too busy for me. But he still finds time to go to all the right parties, make all the right appearances. Last month, he skipped my sixteenth birthday party to go to

another

honorary memorial for Mom. We’re talking caviar and champagne, everyone forgetting to be sad in their designer dresses. When he got home, I said, “You missed my birthday again.” I almost added,

like the last five years

, but I stopped myself.

“I was working,” he said, as if he’s ever not working. At least, in the Before, he had a reason to come home, a reason he cared about. Now he’s out every night, drunk on his own misery.

In my life, there’s always a Before and an After. In the Before, when I was an Oscar nominee for best actress, as one of the youngest stars in history, Mom and I wore matching heart necklaces to the ceremony. In the After, when I was voted Etv!’s Teen Actor of the Year, my mom was dead and my heart was broken.

I don’t remember much about the morning my mom was kidnapped, but I do remember that she wasn’t wearing makeup. For a woman who’d been voted Hollywood’s most beautiful woman three years running by

Celebrity

magazine, that’s a big deal. She didn’t even go to bed without putting on lipstick first. But that day, she dropped her lipstick and didn’t pick it up. We all forgot about it. Dark red melted into the carpet by my room.

Three days later, when the police found her facedown, a knife through her back, an

Etv!

Memorial Special

was broadcast on her life—and every gruesome detail of her death. I saw it only once, but Dad watched it over and over, whiskey glass in one hand, gun in the other.

So when I found a DVD of Mom’s

Etv!

Memorial Special

in my fan mail this morning, I couldn’t bring myself to watch it, but I saw the note. It wasn’t typed on a typewriter, or in cutout newspaper letters, like you see in movies. It was just Times New Roman font, like a business letter. It said:

This is how you die.

Dad wouldn’t believe me if I told him. He thinks I’m imagining all of it: the glimmer of gold, the silver sedan, the eye that is sometimes blue, sometimes brown. But Dad doesn’t notice anything anymore, especially me. Ever since his suicide attempt was splashed across the news, he’s stayed as far away from me as possible. He doesn’t want to remember the way I found him, blood winding down his neck from where the bullet nicked him as he pulled the gun away from his head, just in time; how the news said he’d

attempted

to commit suicide, like it was the only thing he’d ever failed at. Dad doesn’t like to fail, and since he can’t “fix” me, I haven’t told him about the nightmares that wake me up screaming, or about the memories I’ve had of Mom since she died. They always come when I least expect them, and leave me quivering in terror, obsessed with the guilty feeling that somehow, it must have been my fault.

Mary’s the only one who knows about my guilt. Since Dad hired her two years ago, Mary and I have been together seven days a week, twenty-four hours a day. We’re so close, we finish each other’s sentences; we practically breathe at the same time. And she’s not only my bodyguard; she’s the closest thing I have to a mother now that Mom’s gone. Mary knows things about me that no one else does, like the way I haven’t felt happy since Mom died, or the ice that’s frozen inside of me that keeps getting thicker, separating me from the rest of the world.

The ice I’m afraid will crack and tear me apart.

Mary says it’s important to continue working to keep my mind busy. “You’ll

r

emember when you’re

r

eady,” she says, rolling her

r

’s in a thick Latin purr. “Don’t dwell on it.”

I don’t have time to dwell anyway: I always have to be on guard. At home, the paparazzi climb over the fence and pop up in my windows, trying to get shots of me to sell to the papers. At work, I have to watch every step. Sets are dangerous places, according to Mary, and at Star Studios, there are whole sets built to blow up small buildings, light fires, reenact a flood. Some mornings I’m running from wild mechanical beasts, or dodging a hurricane.

You don’t want to be in the wrong place at the wrong time

, Mom used to say, refusing to let me go out with my boyfriend Pierre another Saturday night. Mary used to tell Mom she should let me be a normal teenager. But Mom said I wasn’t a teenager; I was a teen star.

A teen star has a list of rules a mile long: Don’t drink. Don’t do drugs. Don’t curse. Don’t get caught on camera without makeup. Don’t leave the house without a bodyguard. Don’t cry in public. I’ve followed all these rules except one. And Mom was right: tears smear mascara, even the waterproof kind.

Before Mom died, she was always trying to protect me by reading my future in her tarot cards’ inky depths. But she’s not around to tell me what I need to know now, like why someone would want to kill her, or why I’d get a death threat in my fan mail. Or even why, when the police found Mom’s dead body six months ago, she wasn’t wearing her trademark earrings, the ones she was wearing the morning she was kidnapped. The ones Etv! called “the jewels in Hollywood’s crown” when they were being nice, and “the four-million-dollar mistake” when they weren’t. Two five-carat pink diamonds, carved into the shape of roses.

When I get back to my room, Mom’s

Etv!

Memorial Special

DVD in my hand, Mary is already screaming into the phone. “I don’t want Vivian near that scaffolding,” she’s yelling, her black hair popping out of the tight bun on top of her head.

After two years of being together day and night, I know Mary’s expressions like I know my own. When she wakes me up from a nightmare, there are three lines etched into her forehead, freakishly parallel; when she’s nervous that the news cameras are too close, her right eye twitches at two-second intervals; and when Mary’s scared for my safety, or is tightening the security on my set, a blue vein pulses in her left temple. Since directors don’t like changes, and Mary doesn’t like to see me get hurt, the two clash, badly and often. “Or I’m pulling her off set,” Mary threatens into the phone, her lips pursed under her large brown eyes.

Mary’s right to be worried. Last month, when I ditched work to be with my boyfriend Pierre, my body double stepped in for me. That afternoon, while rehearsing one of my scenes, the girl was almost killed when the scaffolding crumpled beneath her.

Of course, it’s not unheard of for people to die on set. A helicopter decapitates an oblivious extra, blanks get replaced with real bullets, a harness rope breaks and an actor plunges to her death. But when an actor who looks identical to you ends up in the hospital, it’s terrifying. And a little voice in your head keeps repeating:

That should have been me.

“And I don’t want that boy near her,” Mary continues, her voice hoarse from yelling. “After what he did last night . . .”

Last night.

Shame and hurt wash over me again, making my head ache and tears spring to my eyes. Pierre, the only boy I’ve ever loved, and ever will, was caught on national TV kissing my best friend. Mary says I need to move on, how there are “lots of fish in the sea” or something, but I don’t think I can.

If he doesn’t want me, why would anyone else?

Not that I blame him for liking my best friend better. Sparrow is gorgeous. She’s got this crazy mane of red hair and she’s so skinny I can practically wrap two hands around her waist, unlike me. I have plain, curly brown hair, and what Mom used to call

curves.

As if baby fat

curves.

Mary slams the phone down and turns to me, the vein slowly fading back into her temple. “You okay, honey?”

Am I okay? How do I answer that?

My mom was stabbed to death, my dad tried to kill himself, my body double was almost crushed by scaffolding, and my only love cheated on me. And I got a death threat for breakfast. So how am I?

Shitty.

“Okay,” I lie.

Mary cracks all the knuckles on her right hand, our symbol for

Just say the word, and I’ll kill him.

It makes me feel a little better.

“Your dad’s looking for you,” she says. “Want me to call him?”

I shake my head and hand her Mom’s

Etv! Memorial

Special

DVD I found in my fan mail. “Just check this out,” I say. “I’ll find Dad.”

I don’t have to look hard; If Dad’s not at work, there’s only one place he’ll be. Every night, I see Dad’s shadow crawling the hallways, looking for something. I don’t know what. But I see where he ends up:

Mom’s dressing room.

Dad goes into Mom’s dressing room every night now. Sometimes I hear his phone ring, sometimes he talks in hushed tones, sometimes the door’s locked when I turn the handle.

Mom’s dressing room used to be my sanctuary, the place where my future was built, because she never left the house without reading my tarot cards first.

The Empress

, she’d say, turning over a willowy, blond beauty that I always thought looked like her. I look more like the Holy Fool: with my square cheekbones, pouty lips, and curly brown hair, I always look startled, like I’m about to fall off a cliff. I usually feel that way too.

But Mom saw more in me than I did. She always said I was stronger than I knew, and she always believed in me, no matter what the reviews said or which of my flaws were pointed out by the press. Dad called her “new age” because she believed in things he didn’t, magical things, like the wisdom of the tarot and zodiac signs and yoga. She used to wake me up by whispering, “The universe is smiling on you today,” and with her around, it seemed true.

Now I’ll never hear that whisper again. It’s been replaced by the caustic beeping of my alarm clock, and a huge, crushing feeling of emptiness. I can’t even look at the cards anymore, because Mom was supposed to teach me the tarot. She was supposed to teach me a lot of things.

Now I feel a drop in my stomach every time I turn the locked handle on her dressing room door at home, the one with the sparkly

P

on it.

P for Pearl, the biggest movie star in decades. My dead mom.

But Dad must have forgotten to lock the door today, because when I turn the handle, it opens. I step into her dressing room, and a shiver prickles up my neck.

Dad’s kept everything

identical

since Mom died: the framed movie poster of

Medusa’s Revenge

, her first starring role, tilted at an angle on her closet door; the crystals strung across the four corners of the room; her tarot cards spread over her dressing table.

Empress

, she called me,

the creature of light.

I shuffle through the deck, glancing at every gold-encrusted card, but I can’t find the Empress.

Where is she?

I open each of the drawers in Mom’s dressing table, but no Empress. I shuffle through the cards again, and then I open her jewelry case. Her emerald collection is still lined up from dark to light, and the diamonds of her necklaces glow like secrets in the plush black velvet. It’s exactly like she left it. That’s why, before I shut the jewelry box, I’m surprised to find something I thought I would never see again:

A pale pink rose, cut from a single pink diamond.

I hate when I don’t remember something about my mom. Anything. Every card in her tarot deck. Her favorite crystal. The famous heart-shaped mole above her lips. But an earring she was wearing the day she disappeared? Impossible.

So as soon as I get to the studio, I go to Dad’s shoot on the main soundstage. He never misses work, so I know I’ll find him there. Dad’s proud of the fact that he’s only missed one day of work in forty years, from his child actor days to his rise to renowned director, but it just makes him seem old to me. Not that his gray mustache isn’t a giveaway that he’s

fifty

, over ten years older than my mom was when she died.

Dad’s got his back to me, but I can picture perfectly what he’s wearing: an angel T-shirt and cowboy boots, his gray ponytail hanging down his back. He thinks it makes him look cool, but it totally doesn’t. Especially since he wears the same clothes

every day

. But Dad can get away with it; he’s got what Hollywood calls “the touch”: everything he touches turns to money.