Voices of Summer: Ranking Baseball's 101 All-Time Best Announcers (56 page)

Read Voices of Summer: Ranking Baseball's 101 All-Time Best Announcers Online

Authors: Curt Smith

Kiner seemed a post-9/11 piece of New York's DNA "as decent a

man as you'll meet in your life," mused Murphy, softly, thoughtfully. "And

a survivor."

Courage shouts in any tongue.

RALPH MINER

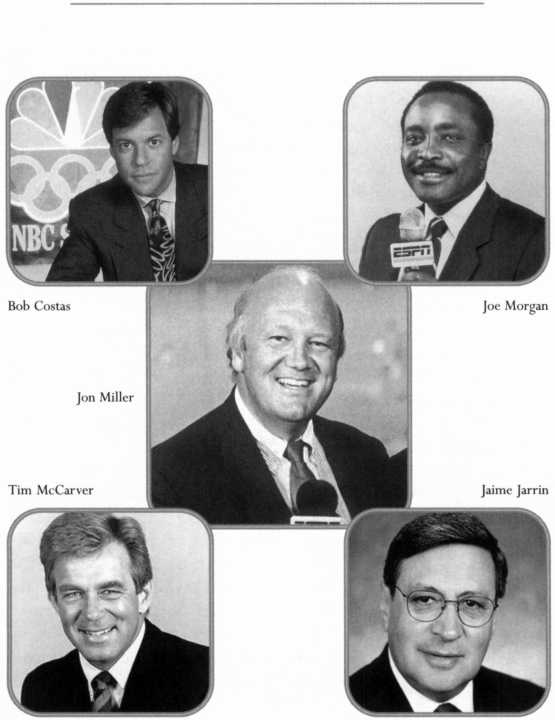

The Smithsonian Institution, June 1993: "I thought Howard Cosell was history's most successful sportscaster," Jack Buck said, "but Bob Costas has surpassed them all." Many in the crowd nodded. "And at his age [411, brother.

I've got older neckties." Growing up, Bob lived for baseball. "It's not a laser

show, not a spectacle. It's just tonight's game."Today he does not announce

his once-Arcadia.

"I'd have given anything to do the Cardinals," Costas said in the 1980s.

Instead, he settled for being among the USA's top-what?-25 celebrities.

Life turned when, in late 1988, NBC TV lost baseball. "Whatever else I did,

I'd never have left `Game of the Week."' On the night of its demise Bob

seemed 36, nearing 63.

His postlogue shows the law of unintended consequences. "Game"'s end

crushed, then freed, him. "Dateline," "Later With Bob Costas," and the

Olympics: what might Bob have missed? Once pining to be Mel Allen, he

may retire owning NBC.

In 1957, John Costas, a Greek electrical engineer, fan, and gambler, took his

five-year-old son to Ebbets Field and the Polo Grounds. Baseball had meant

radio, or black and white TV. "I walk in," said Bob, "and see this green diamond, like the Emerald City." Two years later, the Long Islander sat with a

cousin at Yankee Stadium. Each inning they crept closer, like Dorothy spying

Oz. "Soon we're in left-center's front row and sure a ball'd be hit there: 500

feet, no chance, but 457 a cinch."

The Stadium was renovated in 1974-75. Until then, you could leave via

bullpens on the field. At seven, Costas flanked right field's 344-foot sign. "I

pretend I'm Hank Bauer, jumping up to steal a homer." Next: right-center's

407, glowing on TV. Up-close "Sam Loves Sally" marred the sheen. "I didn't

care what Sam and Sally did on their own time," Bob fumed, "but I couldn't

grasp why they'd desecrate a shrine."

Finally, the Costases stopped at center-field monuments of Babe Ruth, Lou

Gehrig, and Miller Huggins. "[Pre-'74] they were in play [461 feet]. With the

pitcher's mound rising, a kid couldn't see the plate." He could, however, fear.

Bob started crying. Pop asked why.

"Whaddaya mean? The Bambino, Iron Horse, and Little Skipper are

here!" Surely, DiMag and Mick would follow.

Junior heard dad explain being laid to rest. He wasn't buying it: solemnity overwhelmed. "Then he put me on his shoulders for the rest of the walk

around the track. Dad wore a yellow shirt, and smelled like Old Spice. I liked

him a lot that day."

In 1960, the clan left for California. Radio baseball made it bearable. "In

Ohio, we'd pick up Waite Hoyt, later the Braves' Earl Gillespie, Buck and

Caray." Nevada spawned Vin Scully. "Dad said, `That's the Dodgers. We're

almost there."' A Yanks Series made L.A. seem like home. At home, Bob said

he planned to watch each game. "You can send me to school, but you'll never

see me again because I'll run away."

New York trailed, 4-0, led, 7-4, fell, 9-7, and tied Game Seven, 9-all.

Bill Mazeroski retired Costas to his room. "I'm sitting there, eyes welling, as

I take a vow of silence. My initial vow was not to speak until opening day

1961. That impracticality dawned on me quickly. But I kept mute for 24

hours protesting this injustice."

A greater bug was dad, betting up to $10,000 daily: "a terrific storyteller, would meet his bookie on a street, under a lamp," a Philip Marlowe

figure returning East in 1961. Bob got nightly scores in pop's car by turning

the dial: "calibrating it like a safecracker." Phils-Braves could lose their house:

Cubs-Cards, reclaim it. "If his teams were losing, I'd stay outside. Winning,

I'd race inside to tell Dad what was happening." Happening, was love.

"Listening to these announcers, they became the game," he mused. "Its

mythology drew me in. I fell asleep with a transistor under the pillow." Scully

enticed. Saam and Prince seemed voice pals. Allen spellbound: "So much

warmth that a fan relates to readily." His colleague seemed interior: "By now

Barber was bitter, dry, not nearly as good as in Brooklyn." Like Red or Mel,

Bob could have given an hour lecture on each member of the Stripes.

His idol, of course, was No. 7. His company was the world.

Teresa Brewer's "I Love Mickey" spoke to Costas and other Boomers. If you

couldn't fantasize about being Mantle, you were out of it, a nerd. He was

three-time MVP, made 20 All-Star teams, and won the 1956 Triple Crown.

The Switcher could reach first base in 3.1 seconds, but swung to go yard. For

a long time, Bob carried a dog-eared 1958 Mantle All-Star card in his wallet.

"I believe you should carry a religious artifact with you at all times."

On May 22, 1963, Mick's drive hit "[The Stadium facade] like a plane

taking off," said Costas. "Nobody else could do that [literally], or two-strike

drag bunt with the infield back." In 1991, he entered a restaurant to find Mantle and Billy Crystal. For four hours they rehashed his career. "Billy had

grown up on Long Island, idolized Mantle. The whole time Mickey's saying,

`I don't remember that, damn, did that happen, holy sh ... , 'ya know. He

did it. Billy and I remembered it. Tells you something there."

Costas played infield for the Little League Farmington, Connecticut,

Giants, near Hartford. A photo at 10 tells why he chose television. Bob eyes

the lens--eager, intense, and small. "I was good-field, no-hit, and you know

about guys who can't even hit their weight. That was true of me, and I

weighed 1 18 pounds."

At Syracuse University, Bob began working on the campus FM station and

shedding his New York accent. In 1973, he moonlit as WSYRTV fill-in sports

anchor, weatherman, and "Bowling for Dollars" host. Next year the journalism

major trekked to KMOX St. Louis. "You could see," said sports director Buck,

"Bob had the assets"--except for on occasion working on Costas StandardTime.

Bob's first gig was the ABA Spirits of St. Louis. Buck found him in the office

one afternoon. "What are you doing? You've got a game in Providence

tonight." He shrugged. "I got a late-afternoon flight." Delayed, he arrived

near halftime. Next day Jack huffed, "This will not happen again." What did:

the rookie's ability to "talk about anything without a script."

Costas did Missouri and Chicago Bulls basketball and CBS bits and

pieces. In 1979, joining NBC, he swapped barbs with analyst Bob Trumpy.

One week the jets' Richard Todd grabbed a New York Post writer. "You can only

take so much criticism,"Trumpy warned. "After that a reaction is justifiable."

Horsefeathers, said Costas.

"You don't understand the pressures of playing in the NFL," said Trumpy.

"Disproportionate pressures, disproportionate rewards."

Another Sunday Trumpy called Todd's delivery "tragic."

Costas balked: "Ah, Bob, maybe tragic overstates it."

"It is tragic."

"Does that leave any room for a famine, air crash, earthquake, or tornado?"

Trumpy sulked: "I don't care what you say-it's tragic."

A Todd incompletion bared Costas's lance. "And now, tragically, the jets

must punt."

Pundits glowed: What style! What economy of language! Bob's thenspouse was football; his mistress, an old flame. "Baseball's the best sport for an

announcer because of the history and context and it allows for storytelling and

exchange of opinion." Baseball was made for talking: the bar, hotel, or cage.

In 1982, the wonder child turned 30. The Peacocks kindly gave him

"Game." Costas's partner was his childhood shortstop: "I'd grown up

watching Kubek." Looking in a rear-view mirror, he saw the future in its face.

"`Game' was a clearing house. Didn't matter where you were, tune in to

share a baseball feel." Wrigley Field: June 23, 1984. Chicago cabbies still

lower a window: "`Hey, Bob, the [Ryne] Sandberg Game.' That's what they

call it-and it's two decades ago."

At one point St. Louis led, 9-3. Bruce Sutter hurls the ninth. Sandberg

dings to left-center: 9-all. Next inning the Cards refront, 11-9. Chicago's

Bob Dernier walks with two out. Ryne again goes deep-"identical spot, his

fifth hit. The same fan could have caught it." Thousands of Redbirders gasped.

"Game" and Wrigley shook.

"That's the real Roy Hobbs because this can't be happening!" Bob cried.

"We're sitting here, and it doesn't make any difference if it's 1984 or '54-just freeze this and don't change a thing!" It became "a telephone game

[Cubs, 12-111 where you say, `Who likes baseball as much as me?' and call

around the country. `Are you watching? Channel 4, quick.' Absent `Game,'

that can't happen outside post-season. You don't have the stage."

Costas's favorite stage was County Stadium, tending pizza, Polish

sausage, and "secret stadium" bratwurst sauce. "The formula's in a vault. It

tastes like another planet." Brats's arrival signaled an official game. "Tony and

I had to alternate talking because one of us always had a mouthful. This

became [so] legendary" that the Brewers sent him industrial-size brat vats.

"I'd get jars of secret sauce and letters from Cub fans saying Wrigley had

better hot dogs." One Brewman, Ma Pesh, of Stevens Point, Wisconsin,

demanded a brat-eating duel. "In his picture, Ma wears bib overalls, looks 430

pounds, and claims he holds the record for County bratwurst consumption"

-O's-Brewers, August 1972-shocking, Pesh said, since he had never eaten

well vs. Baltimore. "I wrote back, he wrote back, and now we're pals."

County's feel denoted 1956, like Bob's favorite photo from Don Larsen's

perfect game. "Mantle's catching a fly. You've got the bleachers, auxiliary

scoreboard, and shadows October in the Bronx. Could this he any place

but Yankee Stadium? Could Fenway Park be anything but itself?" Another

soulmate: Tiger Stadium: "It's like when I grew up. You couldn't confuse one

park with another."

One "Game," Reggie Jackson cleared the roof. Next up, whistling to

Costas, he pantomimed tying a shoe. "Reggie says that when we're back on the air, he'll enter the box, call time to pretend to tie his shoe, and let us discuss the homer and show his replay."

Jackson singled, touched his helmet, and pointed to the booth. "`Hey,' as

if to say, `it's all a great show."'

All in the family. In the mid-eighties, Bob lost his Mantle card. Tony issued an

SOS. "Game"ers sent fifty Micks. Another week Costas, expecting a child,

lunched with Kirby Puckett, who asked about its sex. Daddy didn't know.

"How about Kirby?" Puckett said. "That works either way."

"Tell you what," Bob posed. "If you're at .350 when he's born, we'll name

him after you." Having never hit .300, Puckett "was above .360" the day Keith

Michael Kirby Costas was born.

At 33, the youngest-ever National Sportscaster of the Year hosted radio's

"Costas Coast to Coast," NBC's Summer Olympiad XXIV, NBA, Super Bowl

XX, XXIII, and XXVII, and pre-game "NFL Live." In 1987, he introduced

Dick Enberg at Cleveland Stadium. "Who needs domes? Who needs artificial

turf? It's cold. It's dark. It feels right. And it's for the championship of the

AFC. Next."