Voyage of the Beagle (19 page)

Read Voyage of the Beagle Online

Authors: Charles Darwin

I heard also some account of an engagement which took place, a few weeks previously to the one mentioned, at Cholechel. This is a very important station on account of being a pass for horses; and it was, in consequence, for some time the head-quarters of a division of the army. When the troops first arrived there they found a tribe of Indians, of whom they killed twenty or thirty. The cacique escaped in a manner which astonished every one. The chief Indians always have one or two picked horses, which they keep ready for any urgent occasion. On one of these, an old white horse, the cacique sprung, taking with him his little son. The horse had neither saddle nor bridle. To avoid the shots, the Indian rode in the peculiar method of his nation; namely, with an arm round the horse's neck, and one leg only on its back. Thus hanging on one side, he was seen patting the horse's head, and talking to him. The pursuers urged every effort in the chase; the Commandant three times changed his horse, but all in vain. The old Indian father and his son escaped, and were free. What a fine picture one can form in one's mind,—the naked, bronze-like figure of the old man with his little boy, riding like a Mazeppa on the white horse, thus leaving far behind him the host of his pursuers!

I saw one day a soldier striking fire with a piece of flint, which I immediately recognised as having been a part of the head of an arrow. He told me it was found near the island of Cholechel, and that they are frequently picked up there. It was between two and three inches long, and therefore twice as large as those now used in Tierra del Fuego: it was made of opaque cream-coloured flint, but the point and barbs had been intentionally broken off. It is well known that no Pampas Indians now use bows and arrows. I believe a small tribe in Banda Oriental must be excepted; but

109

they are widely separated from the Pampas Indians, and border close on those tribes that inhabit the forest, and live on foot. It appears, therefore, that these arrow-heads are antiquarian

1

relics of the Indians, before the great change in habits consequent on the introduction of the horse into South America.

1. Azara has even doubted whether the Pampas Indians ever used bows.

[Several similar agate arrow-heads have since been dug up at Chupat, and two were given to me, on the occasion of my visit there, by the Governor.—R. T. Pritchett, 1880.]

Set out for Buenos Ayres—Rio Sauce—Sierra Ventana—Third Posta—Driving Horses—Bolas—Partridges and Foxes—Features of the Country—Long-legged Plover—Teru-tero—Hail-storm—Natural Enclosures in the Sierra Tapalguen—Flesh of Puma—Meat Diet—Guardia del Monte—Effects of Cattle on the Vegetation—Cardoon—Buenos Ayres—Corral where Cattle are slaughtered.

September 8th.

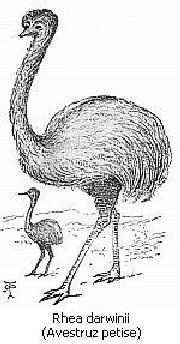

—I hired a Gaucho to accompany me on my ride to Buenos Ayres, though with some difficulty, as the father of one man was afraid to let him go, and another who seemed willing, was described to me as so fearful that I was afraid to take him, for I was told that even if he saw an ostrich at a distance, he would mistake it for an Indian, and would fly like the wind away. The distance to Buenos Ayres is about four hundred miles, and nearly the whole way through an uninhabited country. We started early in the morning; ascending a few hundred feet from the basin of green turf on which Bahia Blanca stands, we entered on a wide desolate plain. It consists of a

111

crumbling argillaceo-calcareous rock, which, from the dry nature of the climate, supports only scattered tufts of withered grass, without a single bush or tree to break the monotonous uniformity. The weather was fine, but the atmosphere remarkably hazy; I thought the appearance foreboded a gale, but the Gauchos said it was owing to the plain, at some great distance in the interior, being on fire. After a long gallop, having changed horses twice, we reached the Rio Sauce: it is a deep, rapid, little stream, not above twenty-five feet wide. The second posta on the road to Buenos Ayres stands on its banks, a little above there is a ford for horses, where the water does not reach to the horses' belly; but from that point, in its course to the sea, it is quite impassable, and hence makes a most useful barrier against the Indians.

Insignificant as this stream is, the Jesuit Falconer, whose information is generally so very correct, figures it as a considerable river, rising at the foot of the Cordillera. With respect to its source, I do not doubt that this is the case; for the Gauchos assured me, that in the middle of the dry summer this stream, at the same time with the Colorado, has periodical floods, which can only originate in the snow melting on the Andes. It is extremely improbable that a stream so small as the Sauce then was should traverse the entire width of the continent; and indeed, if it were the residue of a large river, its waters, as in other ascertained cases, would be saline. During the winter we must look to the springs round the Sierra Ventana as the source of its pure and limpid stream. I suspect the plains of Patagonia, like those of Australia, are traversed by many watercourses, which only perform their proper parts at certain periods. Probably this is the case with the water which flows into the head of Port Desire, and likewise with the Rio Chupat, on the banks of which masses of highly cellular scoriae were found by the officers employed in the survey.

As it was early in the afternoon when we arrived, we took fresh horses and a soldier for a guide, and started for the Sierra de la Ventana. This mountain is visible from the anchorage at Bahia Blanca; and Captain Fitz Roy calculates its height to be 3340 feet—an altitude very remarkable on this eastern side of the continent. I am not aware that any

112

foreigner, previous to my visit, had ascended this mountain; and indeed very few of the soldiers at Bahia Blanca knew anything about it. Hence we heard of beds of coal, of gold and silver, of caves, and of forests, all of which inflamed my curiosity, only to disappoint it. The distance from the posta was about six leagues, over a level plain of the same character as before. The ride was, however, interesting, as the mountain began to show its true form. When we reached the foot of the main ridge, we had much difficulty in finding any water, and we thought we should have been obliged to have passed the night without any. At last we discovered some by looking close to the mountain, for at the distance even of a few hundred yards, the streamlets were buried and entirely lost in the friable calcareous stone and loose detritus. I do not think Nature ever made a more solitary, desolate pile of rock;—it well deserves its name of

Hurtado

, or separated. The mountain is steep, extremely rugged, and broken, and so entirely destitute of trees, and even bushes, that we actually could not make a skewer to stretch out our meat over the fire of thistle-stalks.

1

The strange aspect of this mountain is contrasted by the sea-like plain, which not only abuts against its steep sides, but likewise separates the parallel ranges. The uniformity of the colouring gives an extreme quietness to the view;—the whitish grey of the quartz rock, and the light brown of the withered grass of the plain, being unrelieved by any brighter tint. From custom one expects to see in the neighbourhood of a lofty and bold mountain a broken country strewed over with huge fragments. Here Nature shows that the last movement before the bed of the sea is changed into dry land may sometimes be one of tranquillity. Under these circumstances I was curious to observe how far from the parent rock any pebbles could be found. On the shores of Bahia Blanca, and near the settlement, there were some of quartz, which certainly must have come from this source: the distance is forty-five miles.

1. I call these thistle-stalks for the want of a more correct name. I believe it is a species of Eryngium.

The dew, which in the early part of the night wetted the saddle-cloths under which we slept, was in the morning frozen. The plain, though appearing horizontal, had insensibly sloped

113

up to a height of between 800 and 900 feet above the sea. In the morning (9th of September) the guide told me to ascend the nearest ridge, which he thought would lead me to the four peaks that crown the summit. The climbing up such rough rocks was very fatiguing; the sides were so indented, that what was gained in one five minutes was often lost in the next. At last, when I reached the ridge, my disappointment was extreme in finding a precipitous valley as deep as the plain, which cut the chain traversely in two, and separated me from the four points. This valley is very narrow, but flat-bottomed, and it forms a fine horse-pass for the Indians, as it connects the plains on the northern and southern sides of the range. Having descended, and while crossing it, I saw two horses grazing: I immediately hid myself in the long grass, and began to reconnoitre; but as I could see no signs of Indians I proceeded cautiously on my second ascent. It was late in the day, and this part of the mountain, like the other, was steep and rugged. I was on the top of the second peak by two o'clock, but got there with extreme difficulty; every twenty yards I had the cramp in the upper part of both thighs, so that I was afraid I should not have been able to have got down again. It was also necessary to return by another road, as it was out of the question to pass over the saddle-back. I was therefore obliged to give up the two higher peaks. Their altitude was but little greater, and every purpose of geology had been answered; so that the attempt was not worth the hazard of any further exertion. I presume the cause of the cramp was the great change in the kind of muscular action, from that of hard riding to that of still harder climbing. It is a lesson worth remembering, as in some cases it might cause much difficulty.

I have already said the mountain is composed of white quartz rock, and with it a little glossy clay-slate is associated. At the height of a few hundred feet above the plain, patches of conglomerate adhered in several places to the solid rock. They resembled in hardness, and in the nature of the cement, the masses which may be seen daily forming on some coasts. I do not doubt these pebbles were in a similar manner aggregated, at a period when the great calcareous formation was depositing beneath the surrounding sea. We may believe

114

that the jagged and battered forms of the hard quartz yet show the effects of the waves of an open ocean.

I was, on the whole, disappointed with this ascent. Even the view was insignificant;—a plain like the sea, but without its beautiful colour and defined outline. The scene, however, was novel, and a little danger, like salt to meat, gave it a relish. That the danger was very little was certain, for my two companions made a good fire—a thing which is never done when it is suspected that Indians are near. I reached the place of our bivouac by sunset, and drinking much maté, and smoking several cigaritos, soon made up my bed for the night. The wind was very strong and cold, but I never slept more comfortably.

September 10th.

—In the morning, having fairly scudded before the gale, we arrived by the middle of the day at the Sauce posta. On the road we saw great numbers of deer, and near the mountain a guanaco. The plain, which abuts against the Sierra, is traversed by some curious gulleys, of which one was about twenty feet wide, and at least thirty deep; we were obliged in consequence to make a considerable circuit before we could find a pass. We stayed the night at the posta, the conversation, as was generally the case, being about the Indians. The Sierra Ventana was formerly a great place of resort; and three or four years ago there was much fighting there. My guide had been present when many Indians were killed: the women escaped to the top of the ridge, and fought most desperately with great stones; many thus saving themselves.

September 11th.

—Proceeded to the third posta in company with the lieutenant who commanded it. The distance is called fifteen leagues; but it is only guess-work, and is generally overstated. The road was uninteresting, over a dry grassy plain; and on our left hand at a greater or less distance there were some low hills; a continuation of which we crossed close to the posta. Before our arrival we met a large herd of cattle and horses, guarded by fifteen soldiers; but we were told many had been lost. It is very difficult to drive animals across the plains; for if in the night a puma, or even a fox, approaches,

115

nothing can prevent the horses dispersing in every direction; and a storm will have the same effect. A short time since, an officer left Buenos Ayres with five hundred horses, and when he arrived at the army he had under twenty.