Voyage of the Beagle (47 page)

Read Voyage of the Beagle Online

Authors: Charles Darwin

The puma, after eating its fill, covers the carcass with many large bushes, and lies down to watch it. This habit is often the cause of its being discovered; for the condors wheeling in the air, every now and then descend to partake of the feast, and being angrily driven away, rise all together on the wing. The Chileno Guaso then knows there is a lion watching his prey—the word is given—and men and dogs hurry to the chase. Sir F. Head says that a Gaucho in the Pampas, upon merely seeing some condors wheeling in the air, cried "A lion!" I could never myself meet with any one who pretended to such powers of discrimination. It is asserted that if a puma has once been betrayed by thus watching the carcass, and has then been hunted, it never resumes this habit; but that having gorged itself, it wanders far away. The puma is easily killed. In an open country it is first entangled with the bolas, then lazoed, and dragged along the ground till rendered insensible. At Tandeel (south of the Plata), I was told that within three months one hundred were thus destroyed. In Chile they are generally driven up bushes or trees, and are then either shot, or baited to death by dogs. The dogs employed in this chase

287

belong to a particular breed, called Leoneros: they are weak, slight animals, like long-legged terriers, but are born with a particular instinct for this sport. The puma is described as being very crafty: when pursued, it often returns on its former track, and then suddenly making a spring on one side, waits there till the dogs have passed by. It is a very silent animal, uttering no cry even when wounded, and only rarely during the breeding season.

Of birds, two species of the genus Pteroptochos (megapodius and albicollis of Kittlitz) are perhaps the most conspicuous. The former, called by the Chilenos "el Turco," is as large as a fieldfare, to which bird it has some alliance; but its legs are much longer, tail shorter, and beak stronger: its colour is a reddish brown. The Turco is not uncommon. It lives on the ground, sheltered among the thickets which are scattered over the dry and sterile hills. With its tail erect, and stilt-like legs, it may be seen every now and then popping from one bush to another with uncommon quickness. It really requires little imagination to believe that the bird is ashamed of itself, and is aware of its most ridiculous figure. On first seeing it, one is tempted to exclaim, "A vilely stuffed specimen has escaped from some museum, and has come to life again!" It cannot be made to take flight without the greatest trouble, nor does it run, but only hops. The various loud cries which it utters when concealed amongst the bushes are as strange as its appearance. It is said to build its nest in a deep hole beneath the ground. I dissected several specimens: the gizzard, which was very muscular, contained beetles, vegetable fibres, and pebbles. From this character, from the length of its legs, scratching feet, membranous covering to the nostrils, short and arched wings, this bird seems in a certain degree to connect the thrushes with the gallinaceous order.

The second species (or P. albicollis) is allied to the first in its general form. It is called Tapacolo, or "cover your posterior;" and well does the shameless little bird deserve its name; for it carries its tail more than erect, that is, inclined backwards towards its head. It is very common, and frequents the bottoms of hedgerows, and the bushes scattered over the barren hills, where scarcely another bird can exist. In its general manner of feeding, of quickly hopping out of the thickets

288

and back again, in its desire of concealment, unwillingness to take flight, and nidification, it bears a close resemblance to the Turco; but its appearance is not quite so ridiculous. The Tapacolo is very crafty: when frightened by any person, it will remain motionless at the bottom of a bush, and will then, after a little while, try with much address to crawl away on the opposite side. It is also an active bird, and continually making a noise: these noises are various and strangely odd; some are like the cooing of doves, others like the bubbling of water, and many defy all similes. The country people say it changes its cry five times in the year—according to some change of season, I suppose.

1

1. It is a remarkable fact that Molina, though describing in detail all the birds and animals of Chile, never once mentions this genus, the species of which are so common, and so remarkable in their habits. Was he at a loss how to classify them, and did he consequently think that silence was the more prudent course? It is one more instance of the frequency of omissions by authors on those very subjects where it might have been least expected.

Two species of humming-birds are common; Trochilus forficatus is found over a space of 2500 miles on the west coast, from the hot dry country of Lima to the forests of Tierra del Fuego—where it may be seen flitting about in snow-storms. In the wooded island of Chiloe, which has an extremely humid climate, this little bird, skipping from side to side amidst the dripping foliage, is perhaps more abundant than almost any other kind. I opened the stomachs of several specimens, shot in different parts of the continent, and in all, remains of insects were as numerous as in the stomach of a creeper. When this species migrates in the summer southward, it is replaced by the arrival of another species coming from the north. This second kind (Trochilus gigas) is a very large bird for the delicate family to which it belongs: when on the wing its appearance is singular. Like others of the genus, it moves from place to place with a rapidity which may be compared to that of Syrphus amongst flies, and Sphinx among moths; but whilst hovering over a flower, it flaps its wings with a very slow and powerful movement, totally different from that vibratory one common to most of the species, which produces the humming noise. I never saw any other bird where the force of its wings appeared (as in a butterfly) so powerful in proportion to the weight of its body. When hovering by a flower, its tail is constantly expanded and shut like a fan, the

289

body being kept in a nearly vertical position. This action appears to steady and support the bird, between the slow movements of its wings. Although flying from flower to flower in search of food, its stomach generally contained abundant remains of insects, which I suspect are much more the object of its search than honey. The note of this species, like that of nearly the whole family, is extremely shrill.

Chiloe—General Aspect—Boat excursion—Native Indians—Castro—Tame fox—Ascend San Pedro—Chonos Archipelago—Peninsula of Tres Montes—Granitic range—Boat-wrecked sailors—Low's Harbour—Wild potato—Formation of peat—Myopotamus, otter and mice—Cheucau and Barking-bird—Opetiorhynchus—Singular character of ornithology—Petrels.

November 10th.

—The

Beagle

sailed from Valparaiso to the south, for the purpose of surveying the southern part of Chile, the island of Chiloe, and the broken land called the Chonos Archipelago, as far south as the Peninsula of Tres Montes. On the 21st we anchored in the bay of S. Carlos, the capital of Chiloe.

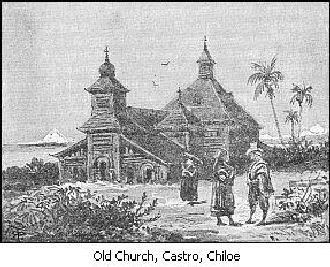

This island is about ninety miles long, with a breadth of rather less than thirty. The land is hilly, but not mountainous, and is covered by one great forest, except where a few green patches have been cleared round the thatched cottages. From

291

a distance the view somewhat resembles that of Tierra del Fuego; but the woods, when seen nearer, are incomparably more beautiful. Many kinds of fine evergreen trees, and plants with a tropical character, here take the place of the gloomy beech of the southern shores. In winter the climate is detestable, and in summer it is only a little better. I should think there are few parts of the world, within the temperate regions, where so much rain falls. The winds are very boisterous, and the sky almost always clouded: to have a week of fine weather is something wonderful. It is even difficult to get a single glimpse of the Cordillera: during our first visit, once only the volcano of Osorno stood out in bold relief, and that was before sunrise; it was curious to watch, as the sun rose, the outline gradually fading away in the glare of the eastern sky.

The inhabitants, from their complexion and low stature, appear to have three-fourths of Indian blood in their veins. They are an humble, quiet, industrious set of men. Although the fertile soil, resulting from the decomposition of the volcanic rocks, supports a rank vegetation, yet the climate is not favourable to any production which requires much sunshine to ripen it. There is very little pasture for the larger quadrupeds; and in consequence, the staple articles of food are pigs, potatoes, and fish. The people all dress in strong woollen garments, which each family makes for itself, and dyes with indigo of a dark blue colour. The arts, however, are in the rudest state;—as may be seen in their strange fashion of ploughing, their method of spinning, grinding corn, and in the construction of their boats. The forests are so impenetrable that the land is nowhere cultivated except near the coast and on the adjoining islets. Even where paths exist, they are scarcely passable from the soft and swampy state of the soil. The inhabitants, like those of Tierra del Fuego, move about chiefly on the beach or in boats. Although with plenty to eat, the people are very poor: there is no demand for labour, and consequently the lower orders cannot scrape together money sufficient to purchase even the smallest luxuries. There is also a great deficiency of a circulating medium. I have seen a man bringing on his back a bag of charcoal, with which to buy some trifle, and another carrying a plank to exchange for a bottle of wine. Hence every tradesman must also be

292

a merchant, and again sell the goods which he takes in exchange.

November 24th.

—The yawl and whale-boat were sent under the command of Mr. (now Captain) Sulivan to survey the eastern or inland coast of Chiloe; and with orders to meet the

Beagle

at the southern extremity of the island; to which point she would proceed by the outside, so as thus to circumnavigate the whole. I accompanied this expedition, but instead of going in the boats the first day, I hired horses to take me to Chacao, at the northern extremity of the island. The road followed the coast; every now and then crossing promontories covered by fine forests. In these shaded paths it is absolutely necessary that the whole road should be made of logs of wood, which are squared and placed by the side of each other. From the rays of the sun never penetrating the evergreen foliage, the ground is so damp and soft, that except by this means neither man nor horse would be able to pass along. I arrived at the village of Chacao shortly after the tents belonging to the boats were pitched for the night.

The land in this neighbourhood has been extensively cleared, and there were many quiet and most picturesque nooks in the forest. Chacao was formerly the principal port in the island; but many vessels having been lost, owing to the dangerous currents and rocks in the straits, the Spanish government burnt the church, and thus arbitrarily compelled the greater number of inhabitants to migrate to S. Carlos. We had not long bivouacked, before the barefooted son of the governor came down to reconnoitre us. Seeing the English flag hoisted at the yawl's masthead, he asked with the utmost indifference, whether it was always to fly at Chacao. In several places the inhabitants were much astonished at the appearance of men-of-war's boats, and hoped and believed it was the forerunner of a Spanish fleet, coming to recover the island from the patriot government of Chile. All the men in power, however, had been informed of our intended visit, and were exceedingly civil. While we were eating our supper, the governor paid us a visit. He had been a lieutenant-colonel in the Spanish service, but now was miserably poor. He gave us two sheep, and accepted in return two cotton handkerchiefs, some brass trinkets, and a little tobacco.

25th.

—Torrents of rain: we managed, however, to run down the coast as far as Huapi-lenou. The whole of this eastern side of Chiloe has one aspect; it is a plain, broken by valleys and divided into little islands, and the whole thickly covered with one impervious blackish-green forest. On the margins there are some cleared spaces, surrounding the high-roofed cottages.