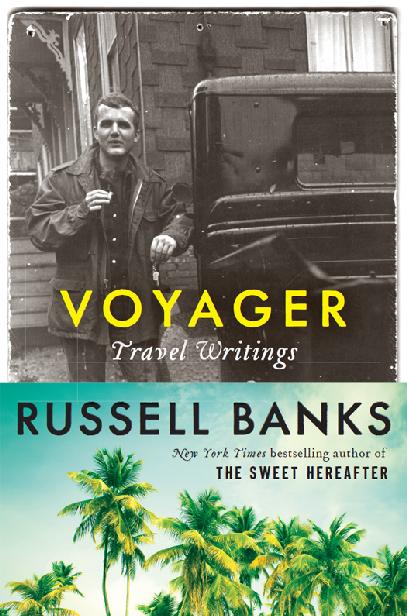

Voyager: Travel Writings

Read Voyager: Travel Writings Online

Authors: Russell Banks

Tags: #Travel, #Essays & Travelogues, #Biography & Autobiography, #Literary, #Caribbean & West Indies

Voyager: Travel Writings

Russell Banks

Ecco (2016)

Rating: ★★★☆☆

Tags: Travel, Essays & Travelogues, Biography & Autobiography, Literary, Caribbean & West Indies

Travelttt Essays & Traveloguesttt Biography & Autobiographyttt Literaryttt Caribbean & West Indiesttt

The acclaimed, award-winning novelist takes us on some of his most memorable journeys in this revelatory collection of travel essays that spans the globe, from the Caribbean to Scotland to the Himalayas.

Now in his mid-seventies, Russell Banks has indulged his wanderlust for more than half a century. “Since childhood, I’ve longed for escape, for rejuvenation, for wealth untold, for erotic and narcotic and sybaritic fresh starts, for high romance, mystery, and intrigue,” he writes in this compelling anthology. The longing for escape has taken him from the “bright green islands and turquoise seas” of the Caribbean islands to peaks in the Himalayas, the Andes, and beyond.

In

Voyager,

Russell Banks, a lifelong explorer, shares highlights from his travels: interviewing Fidel Castro in Cuba; motoring to a hippie reunion with college friends in Chapel Hill, North Carolina; eloping to Edinburgh, with his fourth wife, Chase; driving a sunset orange metallic Hummer down Alaska’s Seward Highway.

In each of these remarkable essays, Banks considers his life and the world. In Everglades National Park this “perfect place to time-travel,” he traces his own timeline. “I keep going back, and with increasingly clarity I see more of the place and more of my past selves. And more of the past of the planet as well.” Recalling his trips to the Caribbean in the title essay, “Voyager,” Banks dissects his relationships with the four women who would become his wives. In the Himalayas, he embarks on a different quest of self-discovery. “One climbs a mountain not to conquer it, but to be lifted like this away from the earth up into the sky,” he explains.

Pensive, frank, beautiful, and engaging,

Voyager

brings together the social, the personal, and the historical, opening a path into the heart and soul of this revered writer.

**

To Chase, the beloved,

and in memory of Ann Hendrie, James Tate,

and C. K. Williams,

Fellow Travelers

As the voyager navigating among the isles of the Archipelago sees the luminous mist lift toward evening and slowly detects the outline of the shore, I begin to make out the profile of my death.

—Marguerite Yourcenar,

Memoirs of Hadrian

CONTENTS

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- Acknowledgments

- PART ONE

- Voyager

- PART TWO

- Pilgrim’s Regress

- Primal Dreams

- House of Slaves

- The Last Birds of Paradise

- Innocents Abroad

- Last Days Feeding Frenzy

- The Wrong Stuff

- Fox and Whale, Priest and Angel

- Old Goat

- Author’s Note

- About the Author

- Also by Russell Banks

- Credits

- Copyright

- About the Publisher

Early versions of some of these writings were previously published in the following magazines and journals:

Brick, Condé Nast Traveler, Conjunctions, Esquire, Men’s Journal, National Geographic,

and

Natural History

. The author is grateful to the editors of these publications, especially to Klara Glowczewska of

Condé Nast Traveler.

A

man who’s been married four times has a lot of explaining to do. Perhaps especially a man in his mid-seventies from northern New England who has longed since boyhood for escape, for rejuvenation, for wealth untold, for erotic and narcotic and sybaritic fresh starts, for high romance, mystery, and intrigue, and who so often has turned those longings toward the Caribbean.

Why the Caribbean? Who can reliably say? Whether arriving as conquistador or castaway, as fugitive financier or packaged tourist or backpacking lonely planeteer, whether costumed as Ponce de León or Robinson Crusoe or Errol Flynn or Robert Vesco or the little-known American writer bearing the name of Russell Banks, early on I got yanked by the bright green islands and turquoise seas of the Caribbean out of myself and home into high-definition dreams that I projected onto my larger world like a hologram. And while some of my dreams were innocent enough or merely naive, like Crusoe’s, and some reckless, like Flynn’s, all of them got broken and re-formed by the reality of the place and the people who lived there: Ponce got slain by the natives on a south Florida beach; Crusoe, meeting Friday, learned humanity and went home a better man; Flynn, sailing to Jamaica, stepped ashore as Captain Blood;

Vesco, conning Fidel, died in jail for it. And Russell Banks, that little-known writer from New England—it’s still unclear what broke and re-formed him there.

It’s certain that something about the Caribbean draws Europeans and, especially, North Americans out of their accustomed lives. One rarely goes there solely to satisfy one’s curiosity. It’s not the semitropical winter climate and the white sands, either—although that’s the usual explanation. That’s what’s advertised. And it’s not the myth of long-delayed, long-desired release from puritanical inhibitions. Also much promoted. One travels to the Antilles driven by vague desires, mostly unexamined, rarely named, never advertised. One goes like a bee to a blossom, as if drawn by some powerful image of prelapsarian beauty and innocence, where life as one has grown used to it at home—polluted and corrupt and cold and erotically constricted and dark—has somehow been kept from the garden. One likes to believe that in the Caribbean there are no snakes. The few found there surely came from elsewhere,

isolatos,

outliers from the north carried by tourists in their luggage.

I was no different. For years I, too, traveled to the Caribbean drawn by unexamined, unnamed desires, until in the late 1970s, still a young man, disillusioned by the poverty and corruption, and embarrassed and angered by what I viewed as my government’s unwillingness to accept responsibility for both, and chagrined by my fellow American tourists, who were arriving in growing numbers in packaged and cruise-shipped hordes, and humbled by my inability to cross the racial and economic and cultural barriers that fenced me in and out, after a half-dozen island-hopping tours and eighteen months of living in rural Jamaica with my second wife, Christine, and our three daughters, I finally packed our bags, and we returned home to New England—for good, I believed—where I tried to stop dreaming up the Caribbean.

But it wasn’t that easy. I thought when I got home that I had wakened, but in my dreams I kept remembering the sharp clarity

of the light, the overwhelming intensity of the landscape, the smell of a wood cook-fire in a country village, the sense-surrounding passion and brilliance of Caribbean music and speech. I remembered the excitement of learning to love a people and place not remotely my own and the stupefying wonder of colliding with a cultural and racial and geographic otherness so extreme that, no matter how hard and honorably I tried to penetrate it, I was left exhausted and confused and excluded. And alone. Especially that. As if I had finally discovered there the meaning and permanence of solitude. Not just my solitude, but everyone’s.

One night in Jamaica I sat by a window in a Port Antonio rooming house that overlooked the silver moonlit bay below, listening to the palm trees chatter in the evening breeze. Fifty miles away, in a country village called Anchovy on the other side of the island, Christine and our three daughters were asleep in our rented house. I was studying scattered dots of light in the jungle-covered hillside that danced their way from the bay up the silhouetted side of the volcanic mountain behind me. I wondered idly if the yellow lights were fireflies—then suddenly realized that those lights are

homes,

you idiot, homes, where real people live out their real lives, hundreds of tiny, one-room, tin-roofed cinder-block and daub-and-wattle cabins lit by candles and smoky kerosene lamps, where men and women and children are living in a reality utterly unlike my own, a world just as subjective as mine, but infinitely more difficult and punishing, their lives and dreams putting the ease and luxury of mine to shame. In the end their inner lives and dreams were for me unknowable. Perhaps it had always been so, but somehow at that moment my own inner life and my own dreams became unknowable. As if they belonged to someone else. As if they were a stranger’s, and I myself had none of my own.

Afterward, back in the United States, my scattered, fragmented memories slowly over the years began to attach to one another and coalesce into a narrative. When Christine and I lived in Jamaica, after years of unraveling and raveling, the sexual and political and

social and economic ties and our shared love for our daughters that for more than a decade had bound us in marriage somehow at last came completely and permanently undone. We did not intend or wish for it, at the time we barely noticed it, and for long afterward neither of us could say how or why it happened.

Narratives based solely on fading, vested memories, i.e.,

memoirs,

are unreliable and tend to be self-serving projections anyhow. To bend, distort, and reshape those memories, hoping to make them into a coherent account I could trust, and expecting in that way both to learn and tell myself the truth of what had destroyed Christine’s and my marriage, I wrote and published a book. It was called

The Book of Jamaica

—a novel, I insisted, not a memoir. Set in Jamaica, it was about a white American man, a university professor more than a little like the author, married to a woman more than a little like the author’s wife.

Reliably narrated or not, in both the reader and the writer fictions engender desire. It’s a paradox, counterintuitive, perhaps; but while an honorable, artistically ambitious, well-constructed work of fiction usually provides resolution, it doesn’t necessarily satisfy or erase one’s desire for a solution. When a novel or a story succeeds in penetrating a mystery, it proceeds at once to raise a further, deeper mystery. In answering one question, it asks a more difficult question that otherwise would never have been raised. For a long time I ignored or simply denied the existence of any mystery beyond the dissolution of my second marriage—as fictionalized in

The Book of Jamaica

—until a decade later, in the late 1980s, a third marriage and divorce later, when contemplating the commencement of a fourth marriage, I found myself drawn back to that further, deeper mystery.

I got invited by a glossy New York travel magazine to make and write about a winter-long, island-hopping journey through the Caribbean. Thirty islands in sixty days. No restrictions as to length. All expenses paid. Tempted by the thought of testing my constructed, decade-old, novelistic narrative against the mystery it

had tried to penetrate, and hoping, if possible, to name the further mystery engendered there, I negotiated a sabbatical semester from my university and accepted the assignment. Chase, the woman I wished to make my fourth wife, was then teaching at the University of Alabama. She agreed to accompany me on my travels into my Caribbean past and the troubles that possibly resided there, troubles whose existence she was not yet aware of. She thought only that it was a posh writing assignment for me, one that happened also to offer her a few months away from Tuscaloosa, which was something she’d been trying to arrange since the day she first arrived from western Massachusetts three years earlier.