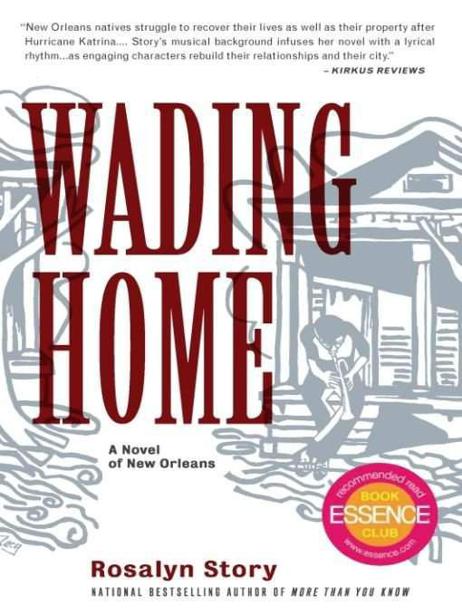

Wading Home: A Novel of New Orleans

Read Wading Home: A Novel of New Orleans Online

Authors: Rosalyn Story

Tags: #Fiction, #General, #New Orleans (La.), #Family Life, #Hurricane Katrina; 2005, #African American families, #Social aspects, #African Americans, #African American, #Louisiana

To my families on both sides, the Story/Williams and the Boswells,

for love, and for history

Storm Warning

Louisiana, 2005

Y

ears before the night the storm made history, it had already earned its name. Those who’d witnessed the worst of them argued that when The Big One finally appeared, it would signal the end of everything in its path. There would be nothing left except the memory of its perfect inception—how it reared its monstrous head over the tropics, then barreled through warm gulf waters that whipped its winds into frenzy before it roared across the thin barrier islands off the mainland toward the coast.

So when the big storm finally trounced in like an unwelcomed though not unexpected visitor, birds flew to cover and a whole city crouched in fear. It pounded the sandy gulf shores, then arced east as the surging waters battered shoddy levees to rage through the city like no other flood before it. Afterwards, 200-year old trees lay uprooted. Hand-built houses passed down through five generations floated away and fell apart. And the lives that survived were forever changed.

Upriver, though, where the winds were calmer, another storm formed under clear skies and bright sun and in the sleep-quiet darkness of night. It shaped in the clouded minds of men, gathered force with ambition, surged with greed and lust. But the uprooting of lives would be as heartbreaking as any hurricane.

A perfect spread of earth one hundred or so miles up from New Orleans, Silver Creek Plantation had begun in 1855 on a whim, a gamble, a bluff made with tongue in cheek. A Frenchman—preacher, planter, and dabbler in games of chance—sat down to a card table with a pair of deuces and got up with 200 acres of God’s garden. A place where tall pines and cypresses and sweetgum shaded the fertile earth, egrets and herons swam through thick air sweetened with honeysuckle and jasmine, and in the creek shallows that necklaced the land like a strand of gurgling silver, crawfish grew nearly as plump as the preacher/gambler’s fists.

Under the sweating brows of the Frenchman’s thirteen new slaves, new life sprang from the freshly tilled soil. Year after year, the rich earth bore crops so magnificent that the Frenchman could scarcely believe his eyes—there was corn as tall as young pines, sugar stalks with the reach of cypress trees, and a cotton crop that stirred the envy of the whole parish.

But if Silver Creek was the preacher’s passion, his true love was the young Ashanti woman with soft, almond eyes and a face shaped like a heart. Anyone who saw the two of them together might wonder who was master and who was slave. And either way they guessed, they would have been right. For as much as the papers the Frenchman owned bound her to him, he was as much bound to her by the grip she held on his heart.

Like the land itself, the Frenchman and the African woman bore generations of hearty fruit, beginning with a son who grew tall, steel-eyed, and strong, and as much in love with the land as the master who sired him. For generations to come it was passed down from father to son, bouncing between legend and fact, that the pear-shaped piece of land was a paradise to which no harm could come. Nothing could stunt its bounty or its beauty, and nothing could pry it from the hands of the Fortiers.

And nothing did, until the season of the big storm.

That year, when the old home folks sat on their porches, they shook their heads and sucked their teeth at the bulldozers that pulled up next to the shotgun cabins, and watched meadows of wildflowers and forests of pine fall to the cold sprawl of golf courses and strip mall parking lots. Some chalked it up to the simple business of men in suits, said the old times were done, and the precious land was too rich anyway for the widowed man who’d chef’d in the kitchens of New Orleans. That the drumbeat and forward march of progress was just the way of things. But others thought there was more to it: that a mysterious death by the roadside was really no accident, but one man’s heartless plan.

Storm nights. A deep, eerie light. The air heavy, thick, and hot. The swaying branch-dance of live oaks, the scramble of birds and squirrels and dogs to safe havens clear of harm’s way. When he was a boy growing up on the land far upriver before he moved to the Crescent City, the chef’s young eyes had opened wide at his father’s tales of the storms down near where the river met the gulf. The ones that ripped trees from their beds and slammed houses into each other, or picked up trucks and tossed them like toys. Or stirred the waters to rise and swallow everything in sight.

But on this eve of the hurricane, his aging eyes are calm, his mind crowded with other thoughts: a piece of paradise in peril miles away, a father he loved in death, and a son he loves more than life. A son who can scarcely find the land that is his birthright on a map.

The old chef looks out the kitchen window at the still-quiet sky over the city and thinks of the places he calls home, the one up where the creek winds through and the one here at the river’s mouth, wondering how long either will survive. He tends his stove—a pot of red beans and rice will surely get him through whatever the days ahead might bring—and waits for the storm.

New Orleans, August 2005

A

cross the whole city stillness lurks like a shadowy intruder: no noise of cars, trucks, buses or streetcars, and instead an unseemly quiet, except for the rustle of the cypress leaves. On the river near its crescent, a moored barge floats, a silent steamboat hugs the dock. And nearby, the

Vieux Carre

stands oddly muted, its rowdiest bars quiet as an empty church.

Up and down the blocks of old Treme, amid the rows of century-old wood-framed houses where neighbors’ music usually seeps from open doors and windows (the oldest Carmier boy’s sousaphone hoots, or Cordelia Lautrec’s little daughter’s piano scales) an eerie music holds, all the random noises of the neighborhood yielding to the stealthy overtures of a storm.

In Simon’s kitchen, a streak of late summer sun angles through backdoor blinds and sends a blade of gold across his stove. The old man stirs a huge iron pot of beans (only Camellia brand will do) for his domino-night supper of red beans and rice. Leaning a bristly chin over the pot, tasting a spoonful of the liquor, he sprinkles a dash of salt with artful, experienced hands as the steam fogs his glasses and his cataract-weakened eyes squint into the pungent whiff of garlic and thyme. He dips the spoon in for another taste, then glances out the thin pane of the backdoor window at the stilllight sky, and sucks his tongue. The sun, usually in slow retreat on August evenings, will surely fade quickly tonight.

With no neighbors’ music to entertain his dinner preparation—most have left town for higher ground, and only the cash-strapped or fearless have hunkered down to brave out the night—Simon hums an old Pops Armstrong standard in a warbled, gritty baritone:

Give meee… a-kiss, to-build, a-dream-onnn….

He keeps stirring the beans as the starch breaks down and thickens the soup, wielding the splintered oak spoon Auntie Maree gave him some sixty years ago. With a clean white hanky from his back pocket, he blots the sweat beading on his forehead and turns down the flame.

A loud

thwack

from the backyard breaks the quiet.

“Aw. No,” Simon groans, knowing what’s happened.

It’s surely what he’s feared for years. Simon wipes greasy fingers on a dish towel, slaps it down onto the counter, and opens the back door to assess the damage.

Sure enough. The giant live oak—planted by his daddy on the day Simon was born seventy-six years ago—now stands an unbalanced amputee, its long bottom limb lying on the ground.

“Ummph, ummph, ummph.” Simon shakes his head, rests a hand on his hip.

That branch was rotten for sure; too many storm seasons, too many nights like tonight.

But he pushes back a thought:

Could be an omen—something about to break apart tonight, something about to change.

Stooping down to the ground slowly and favoring the weak place in his back, he drags the branch to the side of the house, opens the storage shed door, and hauls it inside, lungs winded and legs stiff. He dusts his dry hands on the legs of his khaki trousers. With a wild storm on its way, that big branch could easily take flight and slam somebody’s window, like what happened with the one they called Betsy. Maybe even

his

window. That wouldn’t do.

Maybe he should board up his windows like the DuBois’s up the street. Or maybe he

should

have, before. Too late now. Simon pulls his cotton shirt collar around his neck against the wind whipping through the tall pecans that separate his yard from the Moutons’. The air is heavy, thick and warmish, with clouds curling in quick choreography, the breeze carrying the faintest scent of salt water drifting in from the gulf, the sky changing fast. Looking up in awe, Simon smiles; despite their frightening intent, the shape-shifting clouds are beautiful, plump tufts of gun-metal gray, silver-rimmed, reluctant light still glazing through.

On the west side of the house, next to a pile of chopped wood along the chain link fence, Simon’s herb garden shivers, looking a little wind-whipped. Maybe he should cover it in burlap? He grows everything himself for his cooking, always has, like Auntie Maree taught him. More than thirty years as head chef at a top drawer French Quarter restaurant hadn’t dulled his taste for the freshest basil and thyme he could get, and even now, six years after his last shift at Parmenter’s, he still demanded the best ingredients for his own table, even though he mostly dined alone.

He stoops and snaps off a leaf of the lavender, crushes it in his fingertips, inhales the sweet scent as a slender face blossoms in his mind. Lavender in the garden had been Ladeena’s idea, and on her final birthday he had surprised her with a sachet of homemade potpourri for her sickbed pillow—dried lavender leaves, orange and lemon rind, store-bought cloves. If he’d known the smile his wife surrendered up at that moment would be her last, he’d have framed it in his memory. The other herbs—the oregano, the mint, the basil (now tall as the fence)—bow under the hand he runs across their heads. He will have a lot to repair tomorrow.

Simon glances at his watch; the beans have been on almost an hour now. Sylvia, mad as she was at him, had already said she wasn’t coming, not even to say goodbye. And if none of the men are going to stop by for a bowl or two of the best red beans and rice in town, just as they had done for the last seven years, well then, tough luck for them. This andouille sausage was the best he’d ever made.

He and his buddies in The Elegant Gents were among the oldest members of the neighborhood’s Social Aid and Pleasure Clubs, and didn’t limit their gatherings to the occasional parades through the neighborhood, when they’d strut like black kings in their handstitched shirts of blue paisley and matching hats, white suspenders, and Johnston and Murphy shoes, the hot brass band riffs licking the wind. No, unlike some of the other S&P’s, the Gents were like brothers—friends, old and true. And true friends, at least

his

, made a point of laughing and lying and signifying over cooking pots and dominoes once a week, come hell or high water.

But not hurricane.

A couple of the men, Eddie Lee Daumier and Pierre “Champagne” Simpson, had called, but most hadn’t bothered, just assuming that this time even Simon had the good sense to run for higher ground. Never mind those others, they said, this storm was The One. Hadn’t the mayor and the governor been on the TV all weekend? True, he hadn’t seen that in a while. He’d heard the men in the white shirts and loosened ties talking from the hurricane center, their up-all-night eyes reddened, their voices scratchy with fatigue, and felt for a moment a slight chill. This time there was something fearful in their tone. If he wasn’t mistaken, the governor sure did look a little pale. And the mayor too, bald head shining, his slick, pressed look betraying the scary news, was sounding his own alarm.

Get out. Get out of the city now

.