Waking the Moon (74 page)

Authors: Elizabeth Hand

“Will—will you be going back to school?” I asked softly, late that night. Dylan lay beside me in the heated darkness, his breathing so slow and measured I thought he had fallen asleep.

“No,” he said at last. He rolled over to look at me. “How can I go back there, after all this? I’m going to stay here. In D.C. And marry you, if it’s still okay.”

“Of course it’s okay,” I whispered, kissing him. “It’s the most okay thing in the world. But what will you do?”

“I have a trust fund that my father set up for me. If my—if Angelica ever shows up, well, I guess I’ll have to deal with her then.”

He was silent. Then he said, “I talked to Dr. Dvorkin this morning.”

“You did?” I was surprised and a little ashamed; I still hadn’t called or gone over to see him.

“He said that he could arrange for me to go to the Divine, if I wanted to. I could start in September, get my transcripts sent out from UCLA. He says I won’t have any trouble getting in—I’m a double legacy, whatever

that

is. I guess because of my mother and grandfather di Rienzi.”

I said nothing, thinking of Oliver and the hyacinth, now wilted upon the harvest table downstairs.

“So I thought, if it was all right with you, maybe I might do that. We’d still have a few weeks before the fall term starts.”

“And you won’t mind living with someone who’s older than most of your teachers?” I teased.

He shook his head. “No. Dr. Dvorkin said it’s nobody’s business, anyway—”

“Which it’s not.”

“—and he seems to think I’ll do really well there. He says I’m sort of the ideal student for them, whatever that is. He says they’ve waited a long time for someone like me to come along.”

“Oh, they have, Dylan,” I murmured, drawing him close to me. “And so have I.”

T

HERE IS A WOMAN

in the moon. Dylan and I see her, night after night, her face growing closer to ours until it fills the window, huge and round and white, and we can hear her singing to us in Angelica’s voice. She has Angelica’s face as well, but bleached of all color. Angelica’s emerald eyes washed to grey, Angelica’s hair streaming from her face like clouds, Angelica’s hands the limbs of the willow tree tapping at the window. She is calling to us, she is waking us; she is willing us to follow her. Her hands reach through the window; the glass shatters as the moon engulfs our room and she is everywhere around us, the color of night, the color of milk, the color of bone.

We awaken in each other’s arms. We are in bed, Dylan and I, in the carriage house—the place that Robert Dvorkin, and the

Benandanti,

have given us. Outside the late-night traffic on Capitol Hill murmurs past. A lone taxi trawls for passengers, two college girls call drunkenly to each other on the distant avenue.

With a groan Dylan turns to look out the window. The moon is full. It no longer has his mother’s face, because he is awake now, and he remembers that his mother is gone. But something in the wind tapping at the glass reminds him of Angelica, I can tell, something in its low moaning makes him turn to hug me close to him, his arms tight around my stomach, his fingers moving restlessly, feeling what is there even though I have told him it is much too soon, it will be weeks, maybe months, before we will be able to feel the baby move.

But Dylan knows that she is there—his daughter, Oliver and Angelica’s child as much as his and mine—just as he knows that Othiym is there too, somewhere beyond the rim of the sky and the racing ledge of clouds, someplace where the sky runs black and stars stream down the bowl of heaven like blood in a cauldron.

She is there now. She will be there for the rest of our lives, and our daughter’s life, and perhaps beyond. That vast and dreaming form—sister, mother, daughter, wife—the eternal mystery, lover and destroyer. Othiym Lunarsa.

The woman in the moon.

I

N THE COURSE OF

writing this novel I referred often to the works of many people, chief among them Carlo Ginzburg (whose studies of the benign and very real

benandanti

inspired the fictional

Benandanti),

Paul Faure, Marija Gimbutas, Camille Paglia, Riane Eisler, Robert Graves, Anne Baring and Jules Cashford, Yves Bonnefoy, Rodney Castleden, Charles Pellegrino, Clifford Geertz, Patricia Monaghan, Carl Kerényi, Merlin Stone, Christos Doumas, Sir Arthur Evans, and Jane Harrison, as well as to numerous primary sources from the ancient world. Whenever possible, I have tried not to wander too far from what is currently known or speculated about the various goddess cults of Old Europe and the Mediterranean; an exception is in my use of the Linear A script from the Minoan/Mycenæan cultures, which, insofar as I am aware, continues to confound translators. However, this is a work of

fiction,

an entertainment and improvisation on some classical themes. As the classicist M. P. Nilsson wrote, “gods also have their history and are subject to change.” In no way should my pages be viewed as a critique, reflection, or interpretation of the works of those mentioned above. Any errors of fact contained herein are strictly my own.

Kudos to my wonderful agent, Martha Millard, for everything. Many thanks for all their help to my wonderful American and UK editors, Christopher Schelling and Jane Johnson; to Ellen Datlow, who read this manuscript in its nascent form; to Jennifer Hershey whose insight contributed invaluably to this work; and to Jose Padua, who since 1975 has been feeding my head with poetry and music.

My love to Richard Grant, who introduced me to George Crumb’s string quartet

Black Angels: Thirteen Images from the Dark Land,

from which some of

Waking the Moon’s

chapter titles have been drawn; and who proved himself to be the very model of a modern New Man by taking care of our children and household in the years it took to write this book.

Finally, to all of my old D.C. friends from CUA, NASM, and the Hamline—thanks. You really made it all Divine.

Elizabeth Hand (b. 1957) is the award-winning author of science fiction and fantasy titles such as

Winterlong

,

Waking the Moon

,

Black Light

, and

Glimmering

, as well as the thrillers

Generation Loss

and

Available Dark

. She is commonly regarded as one of the most poetic writers working in speculative fiction and horror today.

Hand was born in San Diego and grew up in Yonkers and Pound Ridge, New York. During the height of the Cold War, she was exposed to constant air raid drills and firehouse sirens, giving her early practice in thinking about the apocalypse. She attended the Catholic University of America in Washington, DC, where she received a BS in cultural anthropology.

Hand’s first love was writing, but many Broadway actors lived in her hometown of Pound Ridge, and by high school she was consumed with the theater. She wrote and acted in a number of plays in school and with a local troupe, The Hamlet Players. After college, writing stories became her primary interest, and the work of Angela Carter cemented that interest. Hand realized that she wanted to create new myths and retell old ones, using a heightened prose style.

Hand’s first break came in 1988 with the publication of

Winterlong

. In this novel, Hand explores the City of Trees, a post-apocalyptic Washington, DC. The story focuses on a psychically enhanced woman who can read dreams and her journey through the strange city with her courtesan twin brother. The book’s success led to two sequels:

Aestival Tide

and

Icarus Descending

. All three novels were nominated for the Philip K. Dick Award.

Beginning with the James Tiptree, Jr. Award–winning

Waking the Moon

, Hand wrote a succession of books involving themes of apocalypse, ancient deities, and mysticism.

Waking the Moon

centers on the Benandanti, an ancient secret society in modern-day Washington, DC. that also appeared in

Black Light

, a

New York Times

Notable Book.

In 1998, Hand released her short story collection

Last Summer at Mars Hill

. The title story won the Nebula Award and the World Fantasy Award. Most recently, she has published two crime novels focusing on punk rock photographer Cass Neary—the Shirley Jackson Award–winning

Generation Loss

(2007) and

Available Dark

(2012).

When Hand isn’t writing stories of decadence and deities, she divides her time between the coast of Maine and London, with her partner, UK critic John Clute. She is a regular contributor to numerous publications, including the

Washington Post

and the

Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction

.

Hand is the oldest of five siblings in a very close-knit family. This photo shows them in 1967, on one of their camping trips to Maine and Canada. All five kids, then under the age of ten, shared a canvas tent with their parents. From left to right: Brian, Patrick, Elizabeth, Kathleen, and baby Barbara. “Maine imprinted on me during this time, which is why I've lived there for the last twenty-five years,” Hand says.

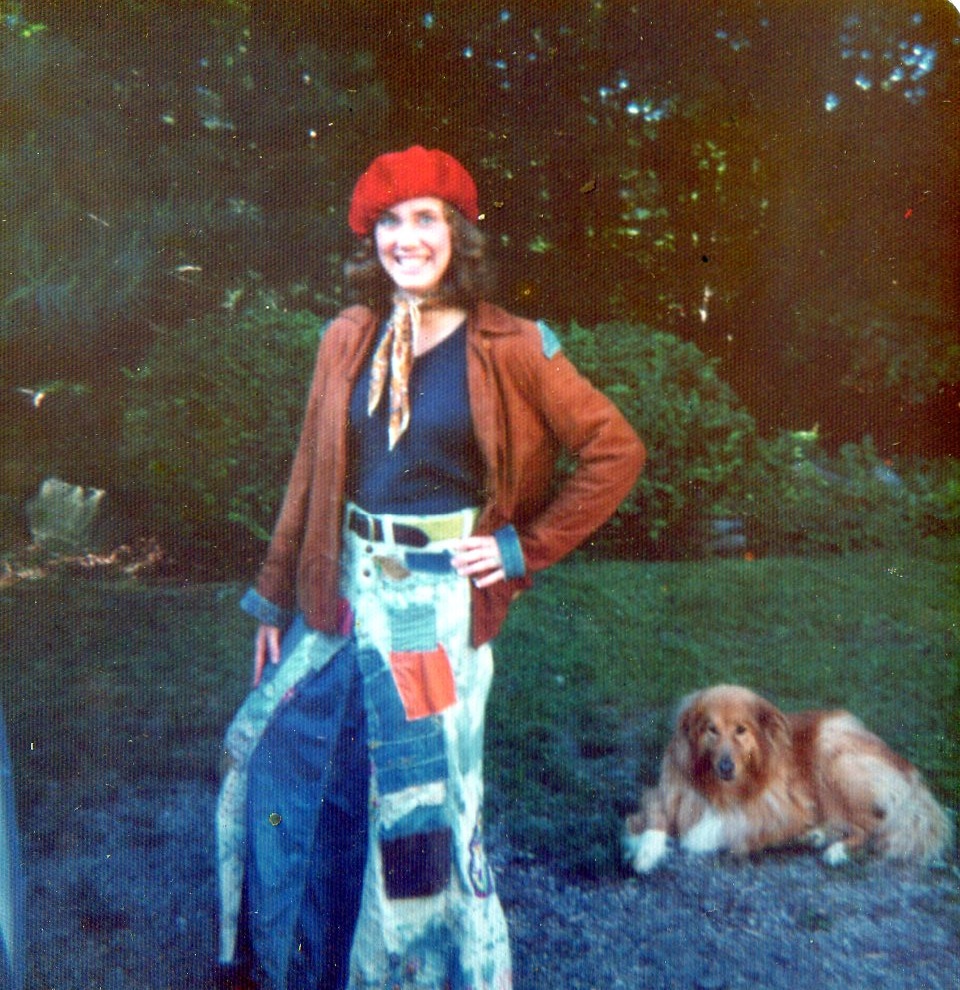

Hand in her driveway with her beloved family dog Cindy shortly before leaving for college in Washington, DC. “Note the skirt, made from a pair of massively embroidered jeans; my favorite red velvet beret, which my mother gave me for Christmas and which disappeared under dark circumstances a few years later; my Mom’s suede jacket (I added the denim cuffs); and needlework belt with my initials on it, made by my grandmother Hand. You can’t see them, but I was also wearing my lace-up Frye boots.”

In her journal, Hand once wrote, “I am being haunted by a town.” The town was Katonah, New York, which she transformed into Kamensic Village, the setting or background for much of her fiction. This photo from 1975 shows the train station where characters Lit and Jamie Casson make their escape at the end of the novel

Black Light

.

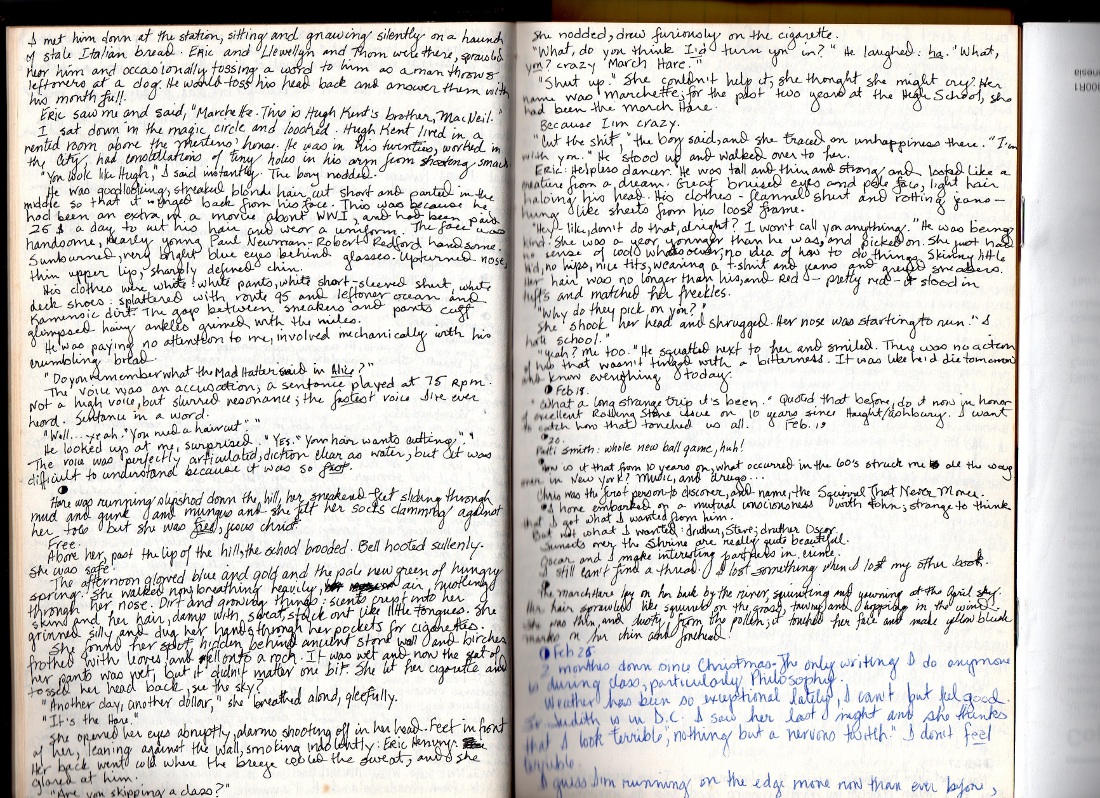

Hand recalls: “In 1976, I was hitchhiking in Putnam County, New York, with my friend Katy. A guy our age picked us up, we drove around and hung out for a few hours, and he then dropped me back at my parents’ house in Pound Ridge. It was only after I got home that I realized I’d left my journal in his car.