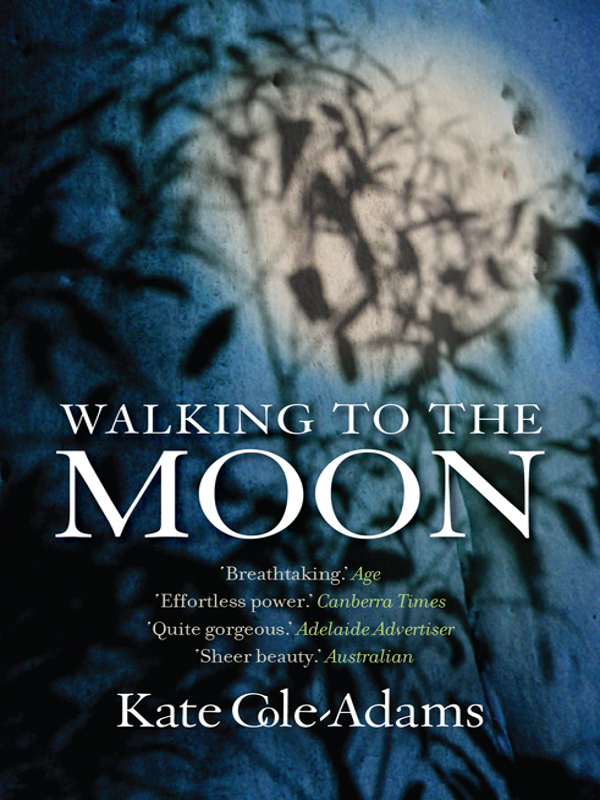

Walking to the Moon

WALKING TO THE MOON

Kate Cole-Adams is a Melbourne-based writer and journalist.

Walking to the Moon

is her first novel, and was shortlisted in the Victorian Premier's Literary Awards (Prize for an Unpublished Manuscript) in 2006.

WALKING TO THE

MOON

Kate Cole-Adams

TEXT PUBLISHING MELBOURNE AUSTRALIA

The paper used in this book is manufactured only from wood grown in sustainable regrowth forests.

The Text Publishing Company

Swann House

22 William Street

Melbourne Victoria 3000

Australia

www.textpublishing.com.au

Copyright © Kate Cole-Adams 2008

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright above, no part of this publication shall be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

First published in 2008 by The Text Publishing Company

This edition published in 2009 by The Text Publishing Company

Typeset in Adobe Caslon by J & M Typesetting

Printed in Australia by Griffin Press

National Library of Australia

Cataloguing-in-Publication data:

Cole-Adams, Kate.

Walking to the moon / author, Kate Cole-Adams.

Melbourne : Text Publishing, 2008.

ISBN 9781921351587 (pbk.)

A823.4

This project has been assisted by the Commonwealth Government through the Australia Council, its arts funding and advisory body.

For my parents, Brigid and Peter

And for their parents and theirs before them

All the way back

Table of Contents

T

oday I walked. Not just those feeble shuffling steps of recent weeks. Today I walked to the base of the hill I have been watching from my window, and then along the rough clay path that circles it. Although we are high here, and far from the sea, the path has the appearance of worn sandstone and contains, along with pebbles and ground-in eucalypt twigs, tiny fragments of shell. There is a world at my feet. Up close it has the texture of a painting. I crouch for maybe five minutes, maybe fifteen. An ochre passage flanked by platinum-tufted grasses; my eyes move slowly between them: the earth with its coloured fragments and the grasses like hair swept back from a face. Time and I have a new arrangement. We leave each other alone.

As I walk back along the path, the light is gathering among the scribbly gums and a worn, animal smell rises from the cooling earth. A king parrot swoops between the trees, swerving only an arm's length from my face. Its belly is saturated with orange and green. It hangs before me then banks away, following the curve of the earth.

By the time I get back to the nursing home, though, I am cold and heavy and shaking. At the gate I stop and lean against the brick pillars. The path across the garden seems impossible. Steff sees me first and sets out across the grass, shaking her head.

âUnbelievable,' she mutters when she is close enough for me to hear. âBloody unbelievable.'

I put my arm around her shoulder, too tired to speak or hold thoughts, and we move slowly, slowly towards the house. Steff doesn't know how to treat me now. She used to call me sleeping beauty. Now she calls me nothing.

âBloody unbelievable,' she says again, when we get upstairs to my room. âSit. Arms. Thermometer. Lie down.'

Then she is gone. As I lie on my side in bed the shivering resolves itself into a slow rhythmic pulse, as if my organsâstomach, kidney, spleenâare clenching darkly on the beat: cold, cold, cold.

The next day I cannot get up. There is no question of even trying. It is not pain. It is more a physical preoccupation, the body taken up entirely with itself. It is a negation of movement. Matter, anti-matter; movement, anti-movement. As if a heavy cloak has been laid upon me.

Steff waits until the younger of the doctors arrives before speaking. âI found her staggering outside in the cold yesterday afternoon. Nearly broke my back getting her up here. Didn't tell any of us she was going, and now she won't eat anything.' She stands looking at the doctor expectantly.

The doctor, who has a round face and sandy hair that he combs back with some sort of oil, looks at me mildly and says, âLet's see now.' He looks in my eyes and ears, checks my blood pressure and temperature, turns away, folding the tourniquet. âI'll pop back tomorrow,' he says, heading for the corridor.

âShe won't eat,' says Steff again, accusingly, as he opens the door. She says it as if I'm doing it deliberately. Won't eat. Won't get well. âTry to eat,' says the mild doctor, turning back briefly. I nod and close my eyes.

âUn-fuckin'-believable,' says Steff when he has gone. She says it to him, not me. Steff only talks to me through a third person. As if she is afraid of sickness.

A heavy cloak has been laid upon me.

It is a forgettable little hill in a forgettable little suburb at the outer edge of town, where housing developments leach into wetlands of migratory birds and across the fields where children once rode ponies. Here the plains that stretch west from Sydney give way to mountains, and the sprawl contracts to a seam of tourist towns that follow the rail line up the sandstone plateaux and cling to the great escarpment I saw as a child.

At first they had me in a hospital in town. When I didn't get better, they sent me here. My husband keeps trying to get me moved back to the city, somewhere with people my own age where I can get what he calls proper help. But Hil wants me here.

âWe need to get her sap flowing again,' she said to the owner, Viv, not long after I first woke up.

âYour niece,' said Viv, glancing towards me, âdoesn't have any sap to flow. Not yet. Leave her with me. We'll do what we can.'

Twice a week Hil catches the train from Central Station. It takes her an hour and ten minutes to get here. âSoon as you're strong enough we'll get you out of here, hey Jess? You know there's a room at my place if you want. Just got to get you on your feet first.'

Slow syrup. Today I will not sit up or look out of the window above my bed. Today I will lie. The late-morning sun slants through the silver birch on to my pillow. I close my eyes, and the shifting dapples settle inside me. There is nothing to regret.

It is just a bump really, my little hill. A child's curved line. It sits on the other side of the oval, rising above its circle of gums. A mound the developers forgot.

Steff comes back before lunch, bringing Tina. Together they manoeuvre me into a wheelchair and push me through to the washroom. Inside, I stand shakily and hold on to a steel rail while Tina helps me remove my clothes. There is a plastic stool in the shower alcove and I lower myself on to it clumsily, without grace.

âBack where she started,' says Steff. She checks the temperature of the spray from the hose before pointing it at the small of my back. âSix weeks since she woke up and she's back to square one.'

âNot really,' says Tina, pulling latex gloves over fingernails sealed in clear polish. âIt's just a setback. She'll be right in a few days. But it wasn't such a brilliant idea, was it, taking off on your own?' This addressed to me, as she raises my left wrist and smooths anti-bacterial body wash into my armpit. She's like a sleek bird, Tina, with her tiny wrists and ankles and her precise movements.

Her skin is very pale and her hair dark and cut very short, and there is a single gold ring in her nose. Watching her gives me pleasure. I try to gather my face into a wry smile for her. Reduced, I can feel the effort in every muscle, the intricate system of ropes and pulleys required for each expression. A lopsided flutter. Too hard.

âHil's going to be really impressed,' says Steff.

The hardest thingâharder than balancing as I pull on my jeans, harder than the old-woman shuffle to the bathroom, harder than making my way step by step down to the dining roomâthe hardest thing is to speak. Even listening sends a grey tide through my body: the arrangement of words and phrases and sentences, balanced upon and within each other; the dead ends and digressions, each requiring energy; the slow accumulation of meaning. Tracking it exhausts me.

In a vase next to my bed are the flowers Hil brought earlier in the week, a cluster of greeny-yellow banksias from home and a broken-off twig of birch taken from the garden.

âDon't let Viv see you nicking stuff from her garden,' warned Tina, only half joking.

Curled again on my side, it is the leaves that now draw my gaze, not the flowers, which seem too bright and upstanding. The tip of the nearest leaf is already turning brown, like wrapping paper. I dwell in sickness, I think to myself. And then, no, not sickness: illness. Dwell and ill. Watery words. Pool. I think of a leaf in cool dark water, and of all the other bits of life that accumulate there and sink. Stems, stamen, antennae, eyes, each dismantled cell by cell by swarms of blind microbes, taken in, transformed, released. The way my mother's hair rose around her that day in the lake, how the cicadas fell silent, the blood booming in my ears like wing beats.