War in My Town (16 page)

Authors: E. Graziani

“You should have seen everyone out there,” Cesar stifled a sob as he spoke.

“Dozens of villagers followed Alcide into Eglio from Sassi. It was like a parade, children and adults, all cheering him on.”

“When he walked into Eglio, people thought they were seeing a ghost,” Eleonora explained.

After our long embrace, Mamma held Alcide at arm’s length and looked up at his weathered face. Her eyes were radiant, more radiant than I had seen them in years. “Alcide. It is you. Thank the Lord, you’ve come home.”

“Yes, it is me,” said my big, tall brother. “I’m so relieved to be home. You don’t know what I went through to get back here.”

Mamma gave him another great hug. “Look at you. You are all skin and bones.” She held his face in her hands. “I’ll get you something to eat!”

“Alcide,” I was the first one to ask, “where have you been all this time?”

He looked down at me and with a huge smile he responded. “I will tell you everything, young lady, but right now I am very hungry.”

Alcide’s eyes looked far away, farther than the remote mountain peaks of San Pellegrino. He had eaten his fill and now he just breathed and looked lovingly around our tiny kitchen. He smiled at my mother as she held his hand. Cesar offered him a cigarette, which he took obligingly. He took a long puff and then with a ghostly quality in his eyes, he began his story.

“I was in Rhodes in the Aegean Sea, serving in the Italian infantry. My work was mostly patrolling the border. Then in 1943, when the Italian government fell, the Nazis took control of Rhodes, the biggest of the Aegean Islands. All the Italian soldiers stationed there were arrested. Most had wanted to change sides and fight with the Allies.

“First we were put on a ship bound for Turkey. In Turkey, we were eventually made to board a train, where we were to be taken to a prisoner of war camp. A handful of us soldiers managed to escape by breaking open the lock on the train car. It was the dead of night and we jumped off the moving train down an embankment. Rapid gunfire followed us, so we lay down flat on the field beside the tracks, praying they would miss. Though I lay as flat as I could, they managed to graze me in the backside. The gunshots bored holes in my pants.”

He laughed at this, while I listened, horrified. “Where were you when you jumped off the train?” I asked.

“We had no idea where we were. All we knew was that we were escaped prisoners of war with no intention of returning to fight for the Fascists.

“Little by little, our group thinned out. Those of us who were left traveled covertly through the mountains, out of sight from the battles around us. We worked in hiding, in Bulgaria for sheepherders and farmers for the rest of the winter. While we waited for spring, we tended to the sheep, labored on the farms and in turn the farmers fed us, clothed us, and allowed us to sleep in their barns.

“The following spring I started my long journey home again, heading northwest into Yugoslavia, crossing the frontiers over the mountains. After months of traveling, I finally crossed the border from Yugoslavia into northeastern Italy. This was the summer after the collapse of the Fascist regime in Europe. I kept going southwest, on foot over the Alps, through villages, dodging minefields and barbed wire fences. The autumn after the end of the war, I walked south through northern Tuscany. By the time I finished, I was exhausted and starving.”

“What a horrifying experience,” Nora interrupted. “You must have felt so alone.”

Alcide nodded and continued. “Yesterday, I finally made it into Castelnuovo where people knew me. They fed me and gave me a place to stay for the night and clean clothes. They wanted me to stay longer, but I couldn’t. I needed to get home. So this morning I set off for Eglio. I climbed the last of the steep hills up to my beautiful mountain village and to my family.” His eyes welled up with tears. “I hoped that I would find you all as I had left you. I heard of the Nazi presence in Garfagnana. I prayed that you were all unharmed.”

“Oh, Alcide, Mamma never gave up hope,” Pina said, her eyes welling up again. “For us it is as though you have risen from the dead.”

“And for me,” said Alcide. “It is like coming back to life.”

“For our family,” I added, “it is a new beginning.”

I was grateful that our little family was reunited. We had outlived the war. It was, at long last, the end of a fearsome upheaval. We had made it through the hard times, thanks to our own resilience and the strength of our mother who had been our rock throughout our lives.

Later that week, I was cleaning out one of my nonna’s dresser drawers, when I discovered an old photo. I recognized the face instantly. It was a photograph of her son, my father, as a young man. After the war, we had begun to receive regular mail from him again. Though he sent us money from time to time, he had no desire to return to us.

Perhaps it was because I was getting older or perhaps it was because of all we had experienced in the last few years of war, but I suddenly saw my mother in a new light. Her dignity and quiet grace had held our family together through very difficult years. She had supported and raised all of us, alone. During the war, she had kept us together as best she could, always including her husband’s parents, my nonno and nonna, as part of our family. I was so proud of her and admired her to the deepest measure, not only because she was my mother, but also because she was a woman of great courage and resolve.

I didn’t know what my life’s journey or my future held in store. But I did know one thing. I could draw strength from my friends, my family, and especially from my mamma, for whatever life would bring to me.

When war came to Eglio, all I could see was the hardship and brutality, the desolation and unfairness. But in the end, our wartime experiences left me with a deep appreciation and understanding of life — an appreciation of every moment that we have to share with the people we love. Perhaps some day, my own children will pass my experiences on to their children, so that they, too, will hear the story of war in my town.

Author’s Note

When I interviewed Bruna, my mother, during the writing of this book, she became tearful many times. I could sense that recalling these events still evoked anxiety in her after all these years. I don’t believe that one ever recovers from such traumatic events. One merely learns to live with the physical and emotional scars. Yet, despite the horror experienced by my family, they did go on to live successful and happy lives.

Bruna did marry Edo. They had my brother, after which they immigrated to Canada. Soon afterwards I was born to Bruna and Edo. My beautiful aunt Mery wed Guido, the young man from Eglio, and they had two equally beautiful daughters. They moved to Canada before my parents did. Aurelia and Dante moved to Pisa where Dante became a

carabiniere,

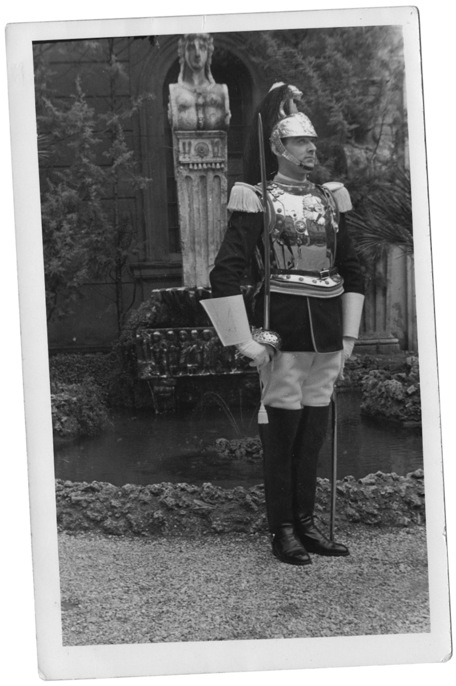

a policeman, and eventually a detective. They were blessed with two boys. Cesar and Ersilia had a son and moved to Val d’Aosta, where Cesar worked after the war blasting and building tunnels. Alcide married Zelinda, and he became a

corazziere

, a special guard to the Italian President. They moved to Rome and had two children. Eleonora married Mario from Florence. They had no children but owned and ran a successful hotel near Florence, where my mother worked soon after the war. Pina worked away from Eglio for a time but eventually returned to take care of my grandmother, Bruna’s mamma, Matilde. Pina never married.

As for Aurelio, Bruna’s father, he never returned to Italy, and though he corresponded regularly with his family and helped to support them, he and his youngest daughter, the heroine of this story, never met.

My mother’s battle with Alzheimer’s Disease inspired me to record this little piece of history for future generations. I hope it inspires you, the reader. These stories of a long-ago war are a testimony to human resilience and the will to survive in the face of extraordinary times — the triumph of the human spirit over terrible adversity that most of us can only imagine. This story is a tribute to everyone in the village of Eglio, those who died and those who survived the Gothic Line occupation.

—E. Graziani

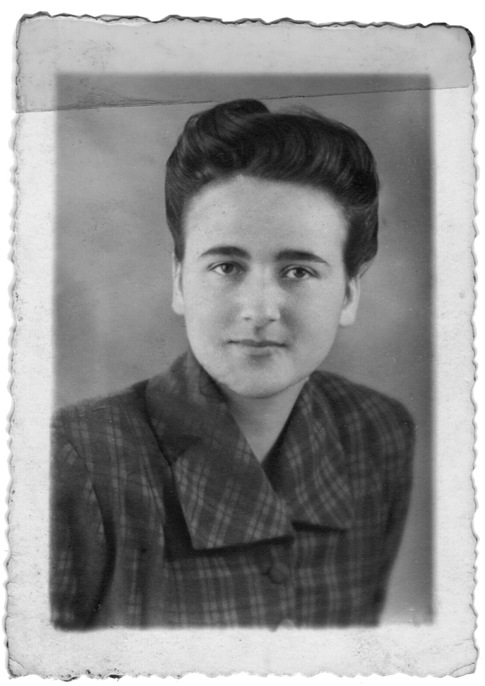

Bruna Pucci, the author’s mother, at 17.

Bruna Pucci, the author’s mother, at 17.

Edo Guazzelli, the author’s father, went for military training, but never engaged in battle.

Edo Guazzelli, the author’s father, went for military training, but never engaged in battle.

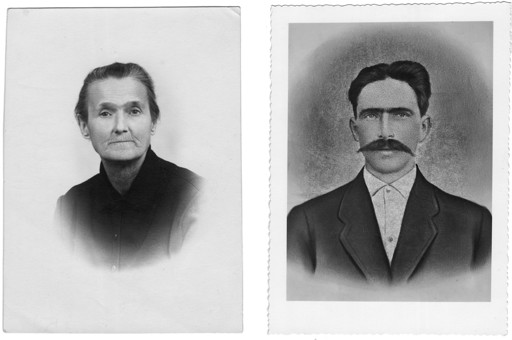

Matilde Lenzarini, Bruna’s mother, married Aurelio Pucci who later worked in Brazil.

Matilde Lenzarini, Bruna’s mother, married Aurelio Pucci who later worked in Brazil.

Bruna’s sister Eleanora (seated at left in her nurse’s uniform) worked at an orphanage in Florence during the war. When she sent this photo home she wrote on the back: “Don’t look at me because I look funny — look instead at my babies.”

Bruna’s sister Eleanora (seated at left in her nurse’s uniform) worked at an orphanage in Florence during the war. When she sent this photo home she wrote on the back: “Don’t look at me because I look funny — look instead at my babies.”

Alcide was Bruna’s youngest brother. He was selected to be a member of the Presidential Special Guard.

Alcide was Bruna’s youngest brother. He was selected to be a member of the Presidential Special Guard.