War: What is it good for? (14 page)

Read War: What is it good for? Online

Authors: Ian Morris

Morally uncomfortable as it may be, though, there seems to be no escaping the facts. What kicked off the long, slow, and still ongoing process of caging the Beast within us was the rise of productive war in the lucky latitudes.

Leviathan Meets the Red Queen

At midnight on February 27, 1991, President George Bush (the Elder) announced a cease-fire in the Middle East. It had taken just a hundred hours for an American-led coalition to annihilate the Iraqi forces that had occupied Kuwait. Two hundred and forty soldiers had been killed from a coalition force of 800,000, as against 20,000 or so of the Iraqi defenders. It was the most one-sided victory in modern history.

In the avalanche of talk shows and op-ed columns that followed, policy wonks increasingly put the triumph down to something extraordinaryâa revolution in military affairs. This, according to the prominent analyst Andrew Krepinevich, “is what occurs when the application of new technologies into a significant number of military systems combines with innovative operational concepts and organizational adaptation in a way that fundamentally alters the character and conduct of conflict.” Such revolutions “comprise four elements: technological change, systems development, operational innovation, and organizational adaptation.” And they lead to “a dramatic increaseâoften an order of magnitude or greaterâin the combat potential and military effectiveness of armed forces.”

Krepinevich identified ten such revolutions in the West in the last seven hundred years, but this is actually just the tip of the iceberg. “There is no new thing under the sun,” the Good Book tells us. “Is there any thing whereof it may be said, âSee, this is new'? It hath been already of old time, which was before us.” And so it is with revolutions in military affairs. The ten thousand years that it took to turn the first violent, poor farmers in the lucky latitudes into the peaceful, prosperous subjects of the Roman, Han, and Mauryan Empires were basically one long string of revolutions in military affairs. We might, in fact, see the various revolutions as merely

moments of particularly rapid change within a single long-term evolution in military affairs.

One of the longest-running debates in biology is between gradualists, who argue that evolution proceeds steadily and consistently, and critics who argue that evolution consists of long periods when not much happens, punctuated by (relatively) short episodes of (relatively) rapid change. The debate will continue, no doubt, but it seems to me that the punctuated model is a very good description of this evolution of military affairs since the end of the Ice Age. On the one hand, tiny changes gradually accumulated across these ten thousand years; on the other, a handful of dramatic revolutions interrupted the story. Different archaeologists might pick out different details, but I will emphasize the coming of fortification, bronze arms and armor, military discipline, chariots, and mass (usually iron-armed) formations of shock troops.

Like the late-twentieth-century military revolution, the immediate causes of all these changes lay in the interaction of technology, organization, and logistics, but in every case the ultimate cause was caging. All the revolutions were adaptations to the new, crowded landscape, and all occurred, in the same sequence, in most parts of the Old World's lucky latitudes (although, for reasons I will come to in

Chapter 3

, not in the New World's). This answers both the questions I raised at the beginning of this chapter: neither the way the Greeks fought at Plataea nor the growth of large, safe societies was a uniquely Western phenomenon. There was no Western way of war.

The people who began cultivating barley and wheat in southwest Asia's Hilly Flanks back around 9500

B.C.

were distinctly low-tech, disorganized fighters. Everything archaeologists have recovered from their graves and settlements suggests that they fought in much the same ways as the simplest agricultural societies observed by anthropologists in the twentieth century. Their deadliest weapons were chipped stone blades. They showed up and ran away as the mood took them. They could rarely campaign for more than a few days before running out of food.

For all these reasons, when anthropologists first encountered modern Stone Age societies, they tended to leap to much the same conclusion as Margaret Mead: that these people were no fighters. The few battles anthropologists saw in New Guinea or Amazonia were desultory affairs. Ragged lines of a few dozen men would form up. Standing just out of effective arrow range, they would taunt each other. Every so often one or two men would run forward, shoot, and then run back again.

The affair might last all day, then break for dinner, and perhaps reconvene the next morning. If someone got hurt, the fight might be abruptly called off. Sometimes, rain was enough to stop play. It all seemed consistent with

Coming of Age in Samoa:

so-called battles were rituals of masculinity, allowing young bloods to show how tough they were without (as Mead put it) playing for very high stakes.

What the anthropologists rarely saw, because few of them could stick around long enough to see it, was that the real Stone Age fighting went on between battles. Battles, after all, are dangerous; anyone who stays put when the arrows fly, let alone runs up to enemies to hit them with a stone ax, stands to get hurt. How much safer to hide, then pounce on people who are not expecting it ⦠which, anthropologists found, was exactly what twentieth-century Stone Age warriors liked to do. A handful of braves would slip into enemy territory. If they caught one or two men from the rival tribe alone, they would kill them; one or two women, they would rape them and drag them home. If they encountered groups big enough to fight back, they hid.

Even better than ambushes, though, were dawn raids, grisly episodes that crop up so often in the anthropological literature that habitual readers become numb to their horror. For a raid, a dozen or more warriors must creep all the way to an enemy village. It is nerve-racking work, and most ventures are abandoned before the killers even reach their destination. But if all goes well, the raiders get to their target during darkness and attack just as the sun rises. Even then, they normally manage to kill just one or two people (often men stepping out to urinate first thing in the morning) before panicking and running away. But sometimes they hit the jackpot, as in this Hopi account of the sack of Awatovi in Arizona around

A.D.

1700.

Just as the sky turned the colors of the yellow dawn, Ta'palo rose to his feet on the kiva

7

roof. He waved his blanket in the air, whereupon the attackers climbed to the top of the mesa and began the assault ⦠They set the wood stacks on top of the kivas aflame and threw them down through the hatches. Then they shot their arrows down on the men ⦠Wherever they came across a man, no matter whether young or old, they killed him. Some they simply grabbed and cast into a kiva. Not a single man or boy did they spare.Bundles of dry chili were hanging on the walls ⦠the attackers pulverized them ⦠and scattered the powder into the kivas, right on top of the flames. Then they closed up the kiva hatches ⦠The chili caught fire, and, mixed with the smoke, burned most painfully. There was crying, screaming, and coughing. After a while the roof beams caught fire. As they flamed up, they began to collapse, one after the other. Finally, the screams died down and it became still. Eventually, the roofs caved in on the dead, burying them. Then there was silence.

Raiding suited Stone Age societies nicely. Their relatively egalitarian way of life meant that no one could enforce the kind of harsh discipline that kept Spartan soldiers standing there while Persians fired arrows at them, but on raids no one needed to expose himself to such dangers. Right up to the last minute, the raiders could run for it if detected. There was almost no risk, except for the virtual certainty that the village being raided would raid back in returnâunless, of course, the raiders killed everyone.

Tit-for-tat raiding and counter-raiding were largely responsible for the appalling rates of violent death in modern Stone Age societies, and the archaeological evidence from prehistoric ones seems consistent with this pattern. Among the twentieth-century Yanomami and in great stretches of highland New Guinea, for instance, raiding got so bad that swaths of land miles wide were left as buffer zones, too dangerous to live in. Once again, there is nothing new under the sun: Caesar reported the same practice in pre-Roman Gaul and Tacitus in Germany, and archaeologists have documented it in prehistoric North America and Europe.

The buffer-zone strategy clearly worked, but it was wasteful, and people must have seen very early that there was an alternative. Instead of abandoning good land, they could build a wall big enough to keep raiders out of their villages. The problem with this, though, was that fortification requires discipline and logistics, just what Stone Age societies are weakest on. Worse still, if village A does organize itself well enough to build a serious wall, the odds are that village B will simultaneously be acquiring the discipline and logistics needed to mount a serious siege.

There is a much-loved scene in Lewis Carroll's

Through the Looking-Glass

in which the Red Queen takes Alice on a madcap race through the countryside. They run and they run, “so fast that at last they seemed to skim through the air,” but then Alice discovers that they're still under the same tree that they started from. “In our country,” Alice crossly tells the queen,

“you'd generally get to somewhere elseâif you ran very fast for a long time.” Astonished, the queen explains things to Alice:

“Here,

you see, it takes all the running you can do, to keep in the same place.”

Biologists have elevated this Red Queen Effect into an evolutionary principle. If foxes evolve to run faster so they can catch more rabbits, the biologists observe, then only the fastest rabbits will live long enough to reproduce, breeding a new generation of bunnies that run faster stillâin which case, of course, only the fastest foxes will catch enough rabbits to thrive and pass on their genes. All the running the two species can do just keeps them in the same place.

During the Cold War, as American and Soviet scientists produced evermore-alarming weapons of mass destruction, this Red Queen Effect was often extended into a metaphor for the madness of war. No one gets anywhere, critics of the arms race argued, but everyone ends up poorer. I will have more to say about this in

Chapters 5

and

6

, but for now I will just make the obvious point that it is very tempting to identify a Red Queen Effect in prehistoric times.

The invention of fortifications is a striking example, though there is some debate about when this happened. As early as 9300

B.C.

, people at Jericho in the Jordan Valley (

Figure 2.4

) built an intimidating tower, but many archaeologists doubt that this had military functions. Even if it did, it seems not to have impressed anyone, because there follows a five-millennium gap in the record before the next case of fortification, a wall dating around 4300

B.C.

at Mersin in what is now Turkey.

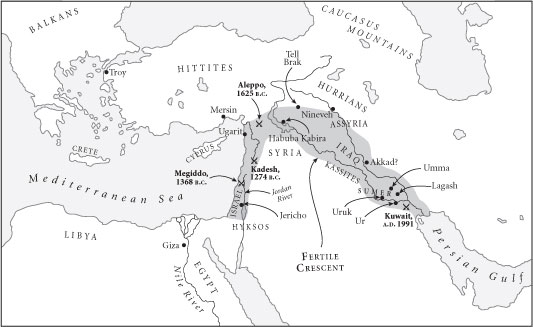

Figure 2.4. The heartland: the sites of the original revolutions in military aff airs, ca. 9300â500

B.C.

After Mersin, fortifications come thick and fast in southwest Asia. By 3100

B.C.

, Uruk in Sumer (modern southern Iraq) had a wall six miles long. It is very impressive, but the evidence of settlements that were destroyed despite the walls their residents built suggests that the organization needed to storm such defenses evolved just as fast as the organization needed to erect them. We might conclude that the Sumerians, like the Red Queen, were running very fast to stay in the same place.

But that is not the full story. By running fast for a long time, farming societies in the core of the lucky latitudes

did

get somewhere else. The fortifications of the fourth millennium

B.C.

are the first revolutionary jump we can detect within the larger evolution of military affairs, and the fact that societies were managing to build these wallsâand to storm those that their enemies builtâmight mean that war was already turning productive. Leviathans were flexing their muscles, making larger, more organized, and probably (although we cannot prove this until we have much more

skeletal evidence to study) more pacified societies, able to pull off tasks that had previously been beyond them. Wars were no longer tit-for-tat raids. Winners were swallowing up losers, creating larger societies.

It was also, however, a nasty process. A Sumerian text from the third millennium

B.C.

, by which time writing had reached the point that poetry could be recorded, gives us a hint of the thousands of voices silenced by the brutality. “Alas!” it laments, “that day of mine, on which I was destroyed!”

The foe trampled with his booted feet into my chamber!

That foe reached out his dirty hands toward me!

⦠That foe stripped me of my robe, clothed his wife in it,

That foe cut my string of gems, hung it on his child,

I was to tread the walks of his abode

.