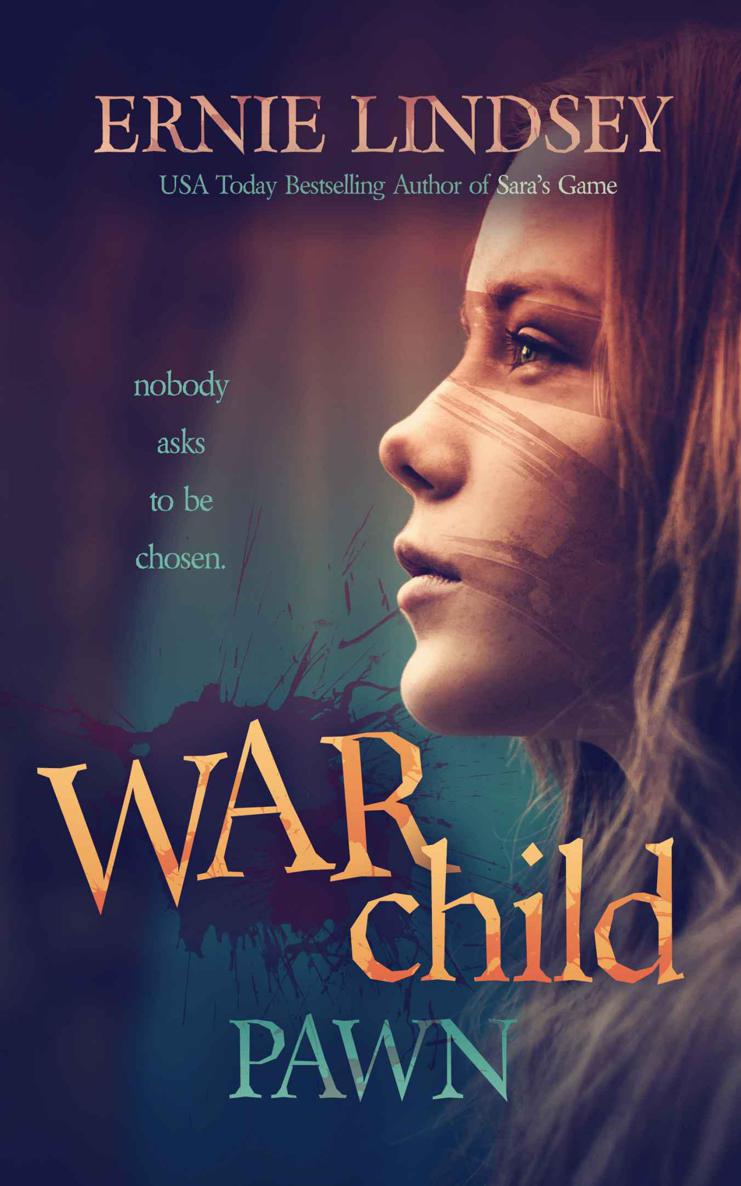

Warchild: Pawn (The Warchild Series)

Read Warchild: Pawn (The Warchild Series) Online

Authors: Ernie Lindsey

Novels

The Sara

Winthrop Series

The Warchild Series

Warchild: Spirit (Book 3) – Coming

Soon

The

Marshmallow Hammer Detective Agency

Novellas

Fang:

Silo Saga (A Kindle Worlds Novella)

Join

Thousands of Readers

The

Lindsey Novel-Dispatch

Free eBooks, News, Giveaways

Okay, so it’s not really your local

paper, but rather a newsletter designed to give you the best options on fiction

by Ernie Lindsey.

You’ll have opportunities to score

free copies of my novels, enjoy steeper discounts on new releases,

automatically have a chance at a $50 Amazon gift card each month, and

participate in all the fun that the rest of us are having.

Sign

Up for The Lindsey Novel-Dispatch

In addition, I’ll often do things

like early cover reveals, interviews with authors you should be reading, and

give general updates on sequels and other cool things happening in the world of

my fiction. Plus, I’ll occasionally have other free content to give out, like

signed books and discount codes for my audiobooks.

Feel free to reach out and say

hello. One of the best parts of being an indie author is easy accessibility to

readers. It makes this whole process worth it.

Join

The Lindsey Novel-Dispatch today

,

and have fun reading Warchild: Pawn!

Ernie

Lindsey

June

2014

“And

a girl shall lead them.”

Don’t ask me how or why

the world ended, because I can’t

tell you. They stopped teaching us about our history long before I was born and

before Grandfather was born. The only connections we have to the past are the

stories the Elders tell around campfires when they’re trying to scare the

children.

Maybe I believe some of these

stories. The tall tales about cars and how people actually drove them—I’ve

never seen one, but it seems possible.

What’s left of the roads, those

dark, hardened paths, cutting through the Appalachian Mountains, crumbling and

filled with holes, they had to be used for something. They go somewhere far,

far from here. But if you’re smart, you stay away. They’re too open, too

exposed. Roving bands of Republicons hide in the hills, waiting on travelers

too tired, or too ignorant, to know that they’ve crossed into the PRV.

The People’s Republic of Virginia.

That’s where I live. If you could

call it living.

We are the depths of what remains. If

you can survive here, you can survive anywhere.

I’m leaving one day.

But first...war is coming.

***

The drums echo down through the

valley, racing across the lake and up the hillside where I’m hiding in a thick

group of rhododendrons. It’s been raining for months, and at first, I think the

heavy, rhythmic booming might be thunder.

Blue sky? I don’t remember what it

looks like.

I know the difference between drums

and thunder, but when you’ve been on point for twenty-four hours, watching,

waiting, scouting—your mind starts to go numb. The crack of a branch might be a

warning of an approaching bear, or the screech of a blue jay might sound like

an arrow flying by your head. It all blends together. They say that when one of

your senses goes, the rest of them work harder to compensate, but when your

mind starts to stumble from exhaustion, they’re all hazy.

I shake my head, clearing out what

cobwebs remain. There it is again.

Boom, boom, ba-boom.

As this ominous sound registers for

what it is, it sends a shot of adrenaline throughout my body and I’m instantly

alert, shocked out of the fog and terrified. The Elders said this would happen.

They didn’t say when, but they knew it was inevitable. Grandfather told me so. He

said that Ellery, the mystic, spoke of it during their last meeting. “War,” was

all she said.

When I lean up on my knees and push

the branches apart, the wet leaves dump their rain puddles into my shirt where

it runs down my back and gives me the shivers. Or maybe it’s the drums. I can’t

tell the difference.

Boom, boom, ba-boom. Boom, boom,

ba-boom.

I cock my ear and listen intently,

just to make sure. Sometimes the younger children will sneak up into the hills

and pretend to have battles. There’s always a fight over who gets to be a part

of the PRV, and who gets to be on the side of the DAV, the Democratic Alliance

of Virginia, our northern enemies. The children play their little drums and

shout and pretend to shoot each other from blinds and tree houses.

But this sound is bigger. Heavier.

Boom, boom, ba-boom. Boom, boom,

ba-boom.

It’s the war rhythm, for sure, which

means it’s coming from a large army. The children’s drums are softer, no bigger

than the buckets we use to carry water. And in fact, that’s what they are—old

buckets with animal hides stretched across the top.

Boom, boom, ba-boom. Boom, boom,

ba-boom.

I strain to hear over the rain

pounding the leaves and the forest floor, trying to figure out how far away the

invaders might be. With all the forest noise amplified by the downpour, it’s difficult

to say. I focus, hard, grinding my teeth together as if that’ll allow me to

hear more clearly. Then I realize they have to be closer than I thought.

Ellery tells stories of how, in the

past, they could hear them coming from two valleys over. But this—no, this is

different—the sound is too defined, the echo is too clear, to be coming from

the other side of Rafael’s Ridge to the north. The trees and underbrush would

dull the sounds if they were that far away.

They’ve crossed the Ridge already,

and I’ll be in trouble for not reporting in soon enough.

If I can’t make it back to our

encampment within a few minutes, we’ll never get prepared in time.

I grab my supply sack—the one filled

with a canteen of water, soggy, rain-soaked bread, and goat cheese—pick up my

slingshot, my bag of hand-picked rocks, and then I run down the hillside,

slipping on the wet leaves and muddy earth, trying to be careful, but hurtling

in a panic at the same time. I don’t want to break an ankle, because if I’m

lying in a writhing heap of pain and can’t make it back to warn the others,

we’re doomed.

I reach the path skirting the lake’s

edge, intact and unbroken, and then push my legs into a hard sprint. My feet

squish inside my boots, and I slip several times on the wet mud, my pack

swinging wildly on my shoulder, but I keep going, running, running, running

between the trees, jumping over downed limbs and rockslides that have happened

because of the constant rain. The ground can only contain so much water before

it loosens its grip and sends the small boulders tumbling down the hillside. I

jump over the same pine tree that’s blocked the path for years. I should know

better—I should remember that the path dips on the other side.

But I’m panicked, not thinking

clearly, and I forget this important fact.

When I land, my boots slide with the

mud, kicking out in front of me, and for a brief moment, I’m airborne, sailing

along, and if I knew that the landing wasn’t going to hurt like hell, it might

be peaceful, almost enjoyable. It seems to take forever, but it can’t be more

than a few feet before I finally land on my backside, my jaws clashing

together, biting my tongue, as I skitter down the decline. Pain arcs from my

tailbone all the way up into my skull, and I taste blood in my mouth. My tongue

throbs. The pain in my back is sharp and blinding, but I get up, and I keep

moving.

Hundreds of lives, everyone in our

encampment, they all depend on me and the other scouts to deliver the reports

so they can gather up their weapons and cover their shacks with an extra layer

of metal or whatever they can find. Mostly, and not very often, maybe once a

month or so, a scout will come hurrying into camp and report that he or she has

spotted a roving band of Republicons.

These raiders, these thieves, travel

in small packs, five to ten of them at most, and they’re easy to fight off. They

don’t like to fight when they don’t have the advantage, and if you can get prepared

swiftly enough, they’ll scope out the situation and move on. But, if they catch

a scout napping and can sneak in unaware, you can count on lost lives and lost

supplies. Our group is especially efficient, and we’ve never been attacked, not

for as long as I’ve been alive. When we instruct new recruits, we train well,

and we train hard, and it’s made all the difference.

Everyone within our encampment knows

how to fight: the Elders, every man, woman and child. The blind and the

limbless. If you can pick up a weapon, any kind of weapon, you’re trained to

use it.

Thankfully, and up until now, we’ve

never had to.

Grandfather says that we haven’t

been invaded in his lifetime, nor in the lifetime of his forefathers. Only

Ellery, the mystic, tells stories of past battles. No one knows how old she is,

and she won’t say. How she’s managed to live this long is anyone’s guess.

Good genetics, maybe. Or altered

genes. Rumors travel on whispers from shack to shack that she’s the last

remaining Kinder. Again, they’re only legends, but the Elders talk of

experiments in the Olden Days, back when there was a government that thought

they were in control. Back before the world ended.

In the clearing off in the distance,

I’m close enough to see wisps of smoke from the encampment. It hangs low over

the rooftops. The heavy air pressure keeps it down, forming a low layer of gray

clouds hovering above the tin roofs.

Another half-mile and I can deliver

the bad news.

Behind me, a round of booming echoes

throughout the valley and races across the lake—the sound travels unhindered,

creating the sensation that they’re closer than what they really are. It’s loud

enough that I wonder if the others back home have heard it already. It’s

possible, and if so, I’m in trouble for not warning them earlier. It’s my

job—any scout’s job—to observe these things long before it has a chance to

reach the ears of those we’re trying to protect.

I run. My lungs and legs ache.

I spit out a mouthful of blood and

gingerly test my tongue against my teeth.

Ouch. Yeah, it still hurts. No need

to test that again.

I’ve been in such a frenzied state,

in a mad dash to get back to safety, that I’ve forgotten something—or someone,

rather.

“Finn,” I say out loud.

He’s my forbidden friend, a member

of the DAV, one of their forward scouts that I met in the forest a year ago.

I think,

Why didn’t he warn me?

And then I keep running.

We met on a sunny afternoon, before

the rains came and rarely stopped, and our first encounter didn’t go well. He

was far away from home. Two hundred miles, at the least, and someone from the

DAV had never been that far south before. Not in my lifetime. Looking back,

that may have been the beginning of their plans. The genesis of their war

machine. I trusted him. I probably shouldn’t have.

That day, I’d been hiding in the

rhododendrons as usual, and I heard something down by the lake. By then, I’d

been on point for over a year and I knew the sounds of the forest well. Which

trees creaked in the wind, which chipmunks lived in which burrows, what time

every morning the herd of deer came through for watering. The new noise was

foreign, so I snuck down to the lake to see what it was.

I found him bent over a stream,

drinking the runoff that feeds into the lake. He surrendered when I held a

knife to his throat. Told me who he was, where he was from, and what he was

doing so far south. I promised not to kill him if he gave me information

whenever he passed through the area. I didn’t see him often, maybe once every

couple of months, but he would always bring me gifts and thank me for sparing

his life. Gifts like apples and cured meat—things we didn’t have the resources

for in my encampment. He brought news, too. News of DAV troop movements, news

of how many groups of Republicons he’d seen in the area, or news of the world

outside our valley.

The information wasn’t worth much,

but I liked hearing about what happened in faraway places. People were still

starving. Rain had washed out ancient bridges and dams. DAV regiments from

Pennsylvania and New York had formed an alliance instead of warring between

themselves.

I kept this information to myself. It

was never important enough to affect our immediate families. This stuff that

happened hundreds of miles away, and in a group where everything was shared,

right down to the same hole in the ground when our bodies required relief. It

felt good, personal, to have something of my own, something that no one else

had. My secrets were mine.

And now maybe they’d cost many

lives.

By the time I make it to the

encampment, I can no longer hear the drums behind me, high up in the valley. The

pounding of the rain on the ground, on scrap-metal roofs and barrels where we

store water for bathing and cooking, drowns out the drumming. I’m relieved,

because I won’t be in trouble for not getting back soon enough, yet it’s also

bittersweet, because they haven’t begun to prepare.

It may already be too late.