Warrior Pose (31 page)

Authors: Brad Willis

CHAPTER 18

Radiation

S

HE CAN'T BE more than five years old, playing quietly with her doll on the floor of the waiting room in the hospital's radiation oncology wing. Her red woolen hat matches her winter coat, hiding the baldness that has resulted from her chemotherapy treatments. Her huge green eyes are missing their luster. Her little cheeks are ashen. Her forehead is etched with a frown. She is deeply absorbed in comforting her doll, whispering that everything will be okay. Her parents sit close by watching her, unable to conceal their anguish and pain.

As a journalist, I would instinctively focus on this child as a poignant way to illustrate the heartbreak and tragic randomness of a killer disease. But I'm no longer behind the camera lens documenting the suffering of others. I'm on the other side now, trying to survive. We're all trying to survive: children, teens, middle-aged adults, a few senior citizens, sitting here together in silence. Waiting in the waiting room. Almost stuck in time. We share a common bond, but there's little eye contact and no conversation. Despite the floral carpet and nature scenes framed on the walls, it's somber. Sterile. I can almost taste the quiet desperation in the room.

The little girl hugs her doll and gives it a kiss on the cheek. I can't take my eyes off her as I wonder if she will survive or if cancer will soon claim her precious little life. I wonder about all of us. No doubt everyone here holds similar thoughts. It's a huge elephant in

the room, and it feels like an eternity before I'm called in to see the radiation oncology specialist, Dr. Chasan.

“It's been three weeks since your surgery, and your scar seems to be healing well,” Dr. Chasan says as she holds my head gently with her hands, slowly turning it side to side to inspect my neck. “We have you scheduled for fifteen treatments over the next seven weeks. You'll finish up just before Christmas day.”

Like Dr. Low, Dr. Chasan won't tell me about my odds for survival. But I do get a new fact from her: The cancer is stage IV. “What does that mean?” I ask quickly when she mentions it. It seems to catch her by surprise. “Oh, I thought you had been told,” she says, sounding a little hesitant. “It can be pretty tough, but we have a good treatment program for you.”

I press for more information, but she artfully dodges. She is very professional, and I begin to realize it's probably an important protocol not to discuss specifics too much with patients, especially if the news is likely to depress them.

“The radiation procedure is painless, you won't feel a thing,” Dr. Chasan gets me back on track as she reaches for a thin, black rubber hose connected to a metal box sitting on the counter. I can see that the hose has an oval-shaped glass tip on the end. “But first, I need to look at your throat and take a few images. Unfortunately, this procedure can be a little uncomfortable.”

I can't imagine any greater discomfort than what I've been living with the past several years, until Dr. Chasan holds the glass tip of the hose closer to my face and says, “This is a tiny camera. I have to insert this tube down one of your nostrils to see what's going on. We need to go in this way to get a full view of the upper throat.”

I take a deep breath through my nose, visualize the process, then swallow hard. “Okay,” I say, “let's do it.”

She sprays a numbing agent into my left nostril and has me breathe deeply through my nose, holding the right nostril shut so the spray penetrates deeply up the left sinus. Sixty seconds later she begins to insert the tube-cam into my left nostril and down the sinus passageway into my throat. Even with the numbing spray, it's worse than I feared. The pain is excruciating as she slowly forces the tube farther.

My right nostril bubbles and foams with mucus. My eyes flood with hot tears. I want to bite onto Dr. Chasan's wrist and chew her hand off to make her stop. I gag and convulse with dry heaves when the camera enters my still-tender throat. It's a complete violation and I can't wait for it to end.

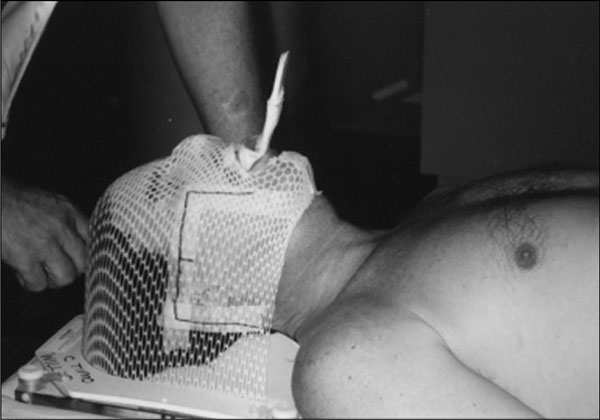

As soon as I settle down after the tube-cam and can breathe normally, I'm guided into radiation. The treatment room is long and wide, with gray metal cabinets and laminated shelving on the walls. Radiation masks are lined up on the higher shelves like rows of skulls. I was fitted for mine three days ago. To construct it, gauze soaked in warm plaster was layered over my face to create a mold. Once dry, the mold was removed and plastic webbing heated inside of it to form the mask. Designed to block the radiation from damaging areas of my face outside the target area where my tonsils once were, it covers my face like I'm the diabolical killer in a cheap horror movie.

The radiation technician, Greg, comes in now and starts to get me prepped. He is chatty and smart. When I ask how radiotherapy works, he gives me an amazingly detailed answer. “It's designed to damage the DNA of cancerous cells with photons, a basic unit of electromagnetic radiation. Cancer cells usually reproduce much faster and in far greater numbers than normal cells, but they have a diminished capacity to repair themselves. So the idea is that the âbad cells' will die while the âgood cells' will have a chance to regenerate.” I know how critical this is. The oncology partner of the doctor who performed my neck surgery told me during a consultation last week that even if the radiation succeeds, there's no way to know if it's one hundred percent, and if the cancer cells begin growing again I have no chance of survival. Zero.

The radiation therapy machine looks similar to the bone scan device, only bigger and more high-tech, built with shiny white, black, and silver metal casings. I'm laid out on yet another long, cold table, this time with my shirt off so the black, pinpoint tattoos on my chest are in plain sight. These were done when I was fitted for my mask, along with two tiny tattoos on my neck. These markers help guide the radiation beams away from sensitive areas. Greg places the horror mask over my face, then sticks a white, wooden dowel into my mouth.

“You have to gently bite on the dowel the entire time to keep your jaw slightly open so radiation doesn't pass through your jawbone,” Greg explains as two more assistants get me perfectly positioned. “That could cause unwanted damage.”

As I hold the dowel in my teeth, the electric table slides me beneath a wide, L-shaped arm that supports the large, round radiation device. It looks like the tip of a giant microscope hovering above me. As I stare at it, I flash back to dissecting insects in high school biology lab and feel like I'm one of the sacrificial bugs we used to squish between glass plates to view through our scopes.

After the clinicians leave the room to protect themselves, the device aims radiation beams from several angles of exposure to intersect at the area where my tonsils used to be. As Dr. Chasan promised, it's painless. I can't feel the beams of radiation at all.

Lying under this machine, it's impossible not to contemplate what my life has become. I keep drifting back into the past, reliving the life I once led. I was fully alive then. My body healthy and strong.

Important things to do. Deadlines to meet. Historic stories to tell. Every day an amazing adventure. Now I'm lying here with a skull mask over my face, biting a wooden stick, and being radiated. I'm so cold, puffy, and pasty white, I feel more like a corpse on an autopsy table than a living human being. “I love you, Morgan,” I hear myself whisper-hissing around the wooden dowel between my teeth. “I love you.”

Radiation Treatment, October 1998.

I'm placed under the giant microscope twice a week. The radiation treatments remain painless, but the side effects are miserable. They give me profound fatigue. My lips are swollen, dried, and cracked, like parched mud. My thyroid gland has been destroyed, which means I have another pharmaceutical medication to take so my body maintains its normal flow of hormones that the thyroid regulates.

My throat feels like burnt toast. Bleeding sores fill my mouth and most of my salivary function has been permanently damaged by the photons. My taste buds have met a similar fate, and my throat is so swollen and inflamed I can't eat regular food and have to drink nourishment through a straw. Dr. Chasan has recommended Slim-Fast smoothies that are used to provide essential nutrients during weight loss programs. They taste terrible to me. If only there were a blended steak and potatoes drink on the market, maybe with a hint of red wine.

Far worse than the Slim-Fast smoothies are the appointments with Dr. Chasan, who continues to periodically force the tube-cam up my nostril and down into my throat, looking for suspect cells, which would appear as black splotches on the bright red lining of my larynx. This procedure remains an inconceivable violation and I loathe entering her office.

Two months later, just before Christmas of 1998, the radiation treatmentsâand the invasive tube-cam sessionsâend. My voice

has gotten much worse than it was right after the surgery. Now I can barely speak in a scratchy whisper that sounds like fingernails on a blackboard. Sometimes my voice disappears completely. I only have two ways to deal with this. When I'm mute, I type on my computer screen in a huge font, then wave my arms and bring Pamela's attention to my message. When I have a semblance of voice, I put on a gadget called a “Chattervox.” It's a plastic, hospital-green amplifier that straps around my waist where the Stim used to go when there was hope of promoting a successful bone fusion in my back. A wire runs from the amplifier to a headset with a microphone. I hiss into the microphone in deep, raw tones and my voice is amplified from the speaker at my belly. It sounds like I've swallowed Darth Vader.

I now understand the word

invalid

in a new way. The noun means someone disabled by illness and injury, but the adjective also comes to mind. I'm not valid. My life lacks validity: a broken back, cancer, no career; incapable of raising my son; helpless, hopeless. I can't imagine how difficult all this is for Pamela. She remains upbeat on the exterior, loving and helping me in every way, sacrificing what little time she has when not taking care of Morgan. But I sense she also has a growing concern for her own future. I don't blame her. Anyone would be frightened, uncertain, and self-protective in a situation such as this. Our relationship has become like a formal dance. We go through all the moves with great politeness and formality, plaster smiles on our faces, have superficial conversations, and barely touch the cancer issue.

My only comfort and sense of worth is when I'm with Morgan. He has no idea that I'm sick as he crawls into my lap on the recliner and we leaf through his little picture books. When I have a voice, I tell him how much I love him through the Chattervox. When I'm mute, I make silly faces and play with him by turning my hand into a crawly thing or giving him gentle tickles. I wish I could sing the lullabies I used to as he drifts off to sleep in my arms. Every time we're together, it's impossible not to be flooded with thoughts of leaving him fatherless. They spin through my head like a tornado and always leave me drowning in grief.