Warriors Don't Cry

Read Warriors Don't Cry Online

Authors: Melba Pattillo Beals

Copyright © 2011 by Melba Beals.

This electronic format is published by Tantor eBooks, a division of Tantor Media, Incorporated,

and was produced in the year 2011.

- Acknowledgements

- Dedication

- Time Brings About a Change: Updating Warriors Don’t Cry in 2007

- Author’s Note from the 1994 Edition

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas

decision, also a warrior who has forged a path with his own life.

Dedication

Elizabeth Eckford

Ernest Green

Gloria Ray Karlmark

Carlotta Walls LaNier

Minnijean Brown Trickey

Terrence Roberts

Jefferson Thomas

Thelma Mothershed Wair

and to our mothers, fathers, and family members who supported us through this incredible experience.

my mother, Lois Marie Pattillo, M.A., Ph.D.

my grandmother, India Annette Peyton

my brother, Conrad Pattillo

my daughter, Kellie Beals

my nephews, Barry and Conrad Pattillo

Warriors Don’t Cry

in 2007

Today, at age sixty-five, I realize she was so right. I am alive and well, and my head is filled with life-event photos, some events that I thought would be my undoing. These days I have little fear of what is to come because I realize it is all ultimately part of a wonderful mystery, unraveling with each day.

But when I first heard Grandmother’s wisdom, I was fifteen years old, frightened, and caught up in the middle of a political firestorm over racial segregation. Eight other teenagers and I stood at the center of the tug-of-war between the U.S. government, Arkansas’s governor, and the angry white mobs intent on halting integration in Little Rock’s Central High School.

At the time, I had no idea of the impact or importance of our successful entry and very difficult year as students inside Central High. It would turn out that our determination to remain in school, despite having to tread through a jungle of hatred and human torture from segregationists, would help to change the course of history and grant access to equality and opportunity for people of color. My younger brother, Conrad Pattillo, would become the first black U.S. Marshal in Arkansas’s history. In the years to follow, a black woman would become Little Rock’s mayor. Many African-Americans would serve in the same legislature that fifty years ago voted to halt integration. And yes, Central High’s population would diversify and even flourish under a black principal.

ON August 20, 2005, hundreds of people, many of them white Arkansans, gathered on the grounds of the Arkansas state capitol for the unveiling of statues of the nine of us. On this day, many of the people who once scorned us have come to congratulate us for standing our ground, for claiming our equality, for completing that year at Central High School against all odds.

This was a place where it is said that the Ku Klux Klan had gathered in their white robes back in 1957 to plan our demise. But today, the area is filled with admirers: whites, blacks, Asians—human beings of every description. There are also more than one hundred news reporters and flashing media cameras; with dignitaries, U.S. senators, state legislators, and ministers; and with the city’s uniformed police officers (yes, members of the same Little Rock force once dispatched to keep us

out

of Central High in 1957) who were there this day to protect us, to ensure passage through the crowds and safe entry onto the stage.

My attention was riveted to the black cloth draped over my statue, which appeared to be even taller than my five feet eight inches, though considerably slimmer than my now senior body. I couldn’t help wondering, What does the statue really look like? Does it truly resemble me at age fifteen?

“Pull the cord—now,” one of the program coordinators whispered. Suddenly my hand reached out, and I pulled. The audience applauded wildly—then fell into a weird, whispering silence. I stood frozen, my eyes and my person riveted on the statue. I thought, My God—it’s me—me, with a ponytail, a young face, a tall, thin body clutching my books to my chest. It is me, poised, ready to attend a day at Central High. I felt as though I must hug this innocent, wide-eyed young girl; I must shelter her wounded spirit.

Suddenly the throng of reporters was pushing forward, moving closer, only a few feet away, determined to get pictures of me and the eight others as we stared at our young images. We nine were oblivious as we examined our younger selves. We were overwhelmed with tears, immersed in the moment, emotionally weeping at the sight of the nine statues, so real, so commanding. When we nine are together, we become one, falling into lockstep, anxious, happy to be together once more. Now we were crying together, grateful we had made it to this moment, alive and celebrating on a spot where we might have been hanged.

THIS year, 2007, marks the fiftieth anniversary of the integration of Central High. To celebrate that occasion, a coin will be available from the U.S. Mint, a Little Rock Museum will be opened, and former President Clinton will host a celebration. It will be a week of galas and joyous cavorting. Huge committees of Little Rock’s finest have convened over the past two years with the sole purpose of creating the right events at the right times to attract people and publicity from around the world.

Going forward, I am grateful for this time of celebration but I don’t want it to obstruct all our perceptions of the fact that there is a lot of work still to be done. We have only survived and triumphed in round one of the bouts that have made and continue to remake America. There are so many more steps to be taken to achieve human equality.

The first round of this battle was never about integration, in my opinion. It was always about

access

—access to opportunity, to resources, to freedom. The enemy was more visible, the battle lines drawn in plain sight. What I call the “new racism” is about

success

—success in terms of cultural, social, and economic status.

I have achieved so much: more than one hundred awards for courage, including this country’s highest award as voted by the U.S. Congress, the Congressional Gold Medal; doctoral degrees and status as a professor and international speaker; and “bling” in many circumstances. And yet, when I go house-hunting, I am often denied the chosen location because to the person selling the house I am just another “maid,” “Aunt Jemima,” or second-class citizen, as always.

Until I am welcomed everywhere as an equal simply because I am human, I remain a warrior on a battlefield that I must not leave.

I continue to be a warrior who does not cry but who instead takes action.

If one person is denied equality, we are all denied equality.

Although this happened over thirty-five years ago, I remember being inside Central High School as though it were yesterday. Memories leap out in a heartbeat, summoned by the sound of a helicopter, the wrath in a shouting voice, or the expression on a scowling face.

From the beginning I kept a diary, and my mother, Dr. Lois Pattillo, a high school English teacher, kept copious notes and clipped a sea of newspaper articles. I began the first draft of this book when I was eighteen, but in the ensuing years, I could not face the ghosts that its pages called up. During intervals of renewed strength and commitment, I would find myself compelled to return to the manuscript, only to have the pain of reliving my past undo my good intentions. Now enough time has elapsed to allow healing to take place, enabling me to tell my story without bitterness.

In some instances I have changed people’s names to protect their identities. But all the incidents recounted here are based on the diary I kept, on news clippings, and on the recollections of my family and myself. While some of the conversations have been re-created, the story is accurate and conveys my truth of what it was like to live in the midst of a civil rights firestorm.

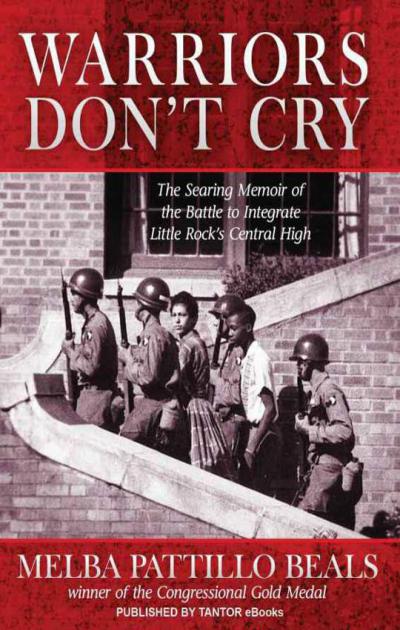

During my junior year in high school, I lived at the center of a violent civil rights conflict. In 1954, the Supreme Court had decreed an end to segregated schools. Arkansas Governor Orval Faubus and states’ rights segregationists defied that ruling. President Eisenhower was compelled to confront Faubus—to use U.S. soldiers to force him to obey the law of the land. It was a historic confrontation that generated worldwide attention. At the center of the controversy were nine black children who wanted only to have the opportunity for a better education.

On our first day at Central High, Governor Faubus dispatched gun-toting Arkansas National Guard soldiers to prevent us from entering. Mother and I got separated from the others. The two of us narrowly escaped a rope-carrying lynch mob of men and women shouting that they’d kill us rather than see me go to school with their children.