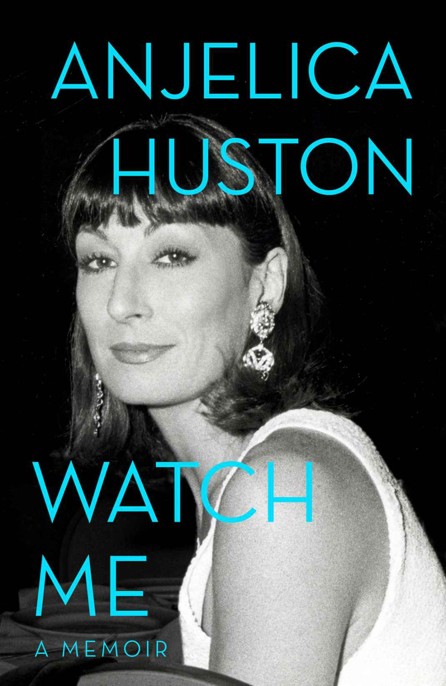

Watch Me: A Memoir

Read Watch Me: A Memoir Online

Authors: Anjelica Huston

Tags: #actress, #Biography & Autobiography, #movie star, #Nonfiction, #Personal Memoir, #Retail

Thank you for downloading this Scribner eBook.

Join our mailing list and get updates on new releases, deals, bonus content and other great books from Scribner and Simon & Schuster.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

CONTENTS

For Bob Graham

PART ONE

LOVE

Photographed by Bob Colacello

CHAPTER 1

M

y old life ended and my new life began as I was standing next to a baggage carousel in the customs hall at LAX in March 1973. It was there, at the age of twenty-one, that I parted ways with Bob Richardson, the man I had lived with for the last four years, a bold and provocative fashion photographer twenty-four years older than I, with whom I’d been involved in a tempestuous affair. Until this moment we had been sharing an apartment in Gramercy Park, New York. Had it not been for the presence of my father and his latest wife, Cici, with whom Bob and I had just been vacationing in La Paz, Mexico, I doubt that I ever would have had the final stroke of courage it would take to leave him.

I would be staying temporarily at the ranch house in the Pacific Palisades that Cici had owned prior to her marriage to Dad and that she was redecorating to accommodate some treasures from our old life at St. Clerans, a pastoral estate in the west of Ireland where I grew up with my brother Tony—before we moved with our mother to London; before the birth of my half siblings, Danny and Allegra; before I acted in a movie at the age of sixteen with my father directing; before my mother’s death by car crash in 1969, a cataclysmic experience that for me ended that beautiful, hopeful decade, when I moved from England to America.

One morning early in my stay at Cici’s, I ordered a taxi and told the driver to take me to Hollywood. “Do you mean Vine Street?” he asked vaguely. I had guessed that Hollywood wasn’t really a place but rather a state of mind, with a great many parking lots sandwiched between shops and storefronts advertising sex and liquor.

But oddly, there was a sense of coming home to California. Although I had grown up in Europe, I was born in Los Angeles. The desert skies were clear blue and untroubled. Living with my father again felt strange, but he would be leaving soon to resume work on

The Mackintosh Man

in New York.

I was eager to buy some marabou bedroom stilettos to match the pink swan’s-down-trimmed negligee that Cici had generously just given me. Driving along Sunset in the pale sunshine, I noticed that the panorama was bare and garish, mostly warehouses and two-story facades. There were rows of tall palm trees and purple jacarandas. The air was windy and dry and sweet-scented. Beverly Hills, it seemed, was all about who you were, what you were driving, your pastimes, and your playgrounds.

A few days before, Cici had taken me shopping on Rodeo Drive, where there was a yellow-striped awning above Giorgio’s boutique, with outdoor atomizers that puffed their signature Giorgio perfume. Indulgent husbands drank espresso at a shiny brass bar inside as their wives shopped for feathered gowns and beaded cocktail dresses. For lingerie, the local sirens went to Juel Park, who was known to seal the deal for many aspirants based on the strength of her hand-stitched negligees and satin underwear trimmed with French lace. We lunched at the Luau, a Polynesian watering hole, the darkest

oasis on the street, where you could hear rummy confessions from the next-door booth as you tucked behind your ear a fresh gardenia from the scorpion punch. Los Angeles was a small town then; it felt both incredibly glamorous and a little provincial.

Cici, who was in her mid-thirties, had a son, Collin, by a former marriage to the documentary filmmaker and screenwriter Walon Green. Cici had gone to private schools in Beverly Hills and Montecito, and her friends were the hot beauties of the day, from Jill St. John and Stefanie Powers to Bo Derek and Stephanie Zimbalist—glamorous sportswomen and great horseback riders who had grown up privileged in the western sunbelt. She had played baseball with Elvis Presley at Beverly Glen Park in the fifties and roomed with Grace Slick at Finch College in New York. Cici also had a lively retinue of gay friends who were sportive and gossipy and informal.

Cici’s energy was buoyant. She cursed like a sailor and loved a bit of illicit fun, as did I. Our practice, at least a couple of times a week, was to do an impromptu raid on other people’s gardens in the neighboring canyons. I would wield the shears, and with a trunkful of flowers and branches, Cici would drive her candy-apple-red Maserati like a getaway car, burning rubber to peals of laughter; although we tempted fate, for some miraculous reason we never got caught. Sometimes Allegra would accompany us on these forays.

After the sale of St. Clerans, Allegra had moved in with her Irish nanny, Kathleen Shine, whom we called “Nurse,” to share a rented house in Santa Monica with Gladys Hill, Dad’s co-writer and secretary. Heartbroken by the death of our mother and still painfully loyal to her, Nurse had been a staple

of Tony’s and my childhood. Gladys was calm, deliberate, intelligent, and kind. A pale-complexioned woman with ice-blond hair from West Virginia, she was devoted to Dad and shared his passion for pre-Columbian art. She had worked for him in the previous decade and was part of the family in Ireland when I was growing up.

Allegra was going on nine and was extremely smart; it was already her intention to go to Oxford University. From the time she was a baby, she’d had an innate, deep wisdom and a sweet formality about her.

I looked up Jeremy Railton, a handsome Rhodesian friend from my former life, when I was going to school in London. He had been designing the sets for a play by Ntozake Shange,

For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide When the Rainbow Is Enuf

, and was living in an apartment on Fountain Avenue. We picked up our friendship where we’d left off five years before. He introduced me to his social circle, which included the comedy writer Kenny Solms and his collaborator, Gail Parent; the talent agent Sandy Gallin; Michael Douglas and Brenda Vaccaro; Paula and Lisa Weinstein; and Neil Diamond. Kenny and Gail wrote for

The Carol Burnett Show

and numerous television specials for Mary Tyler Moore, Dick Van Dyke, and Julie Andrews.

Cici knew that I was still shaken from my split with Bob Richardson. She did her best to take me out and introduce me to people, but I was more interested in riding her horses and walking in the next-door garden. She and Dad had just celebrated the completion of a new Jacuzzi, and one afternoon I found the actor Don Johnson and a male friend of his floating in it. Though I was grateful to Cici for her efforts, I was somewhat embarrassed and ran back to the camellia trees.

A Swedish friend of hers, Brigitta, who owned Strip Thrills, a dress shop on Sunset, told Cici that she was going to a party at Jack Nicholson’s house that evening and invited her to come along. Cici asked if she could bring her stepdaughter, and Brigitta said fine, that it was his birthday, and Jack loved pretty girls.

I borrowed an evening dress from Cici—black, long, open at the back, with a diamanté clasp. Brigitta and another Swedish girl picked us up, and the four of us drove in Brigitta’s car to Jack’s house on Mulholland Drive, on a high ridge separating Beverly Hills from the San Fernando Valley on the other side. It felt like we were on top of the world.

The front door of a modest two-story ranch-style house opened, and there was that smile. Later, after he became a superstar and was on the cover of

Time

magazine, Diana Vreeland was to christen it “The Killer Smile.” But at the time I thought, “Ah! Yes. Now, there’s a man you could fall for.”

In 1969, when I was still living in London, I had gone with some friends to see

Easy Rider

in a movie theater in Piccadilly Circus, and had returned alone some days later to see it again. It was Jack’s combination of ease and exuberance that had captured me from the moment he came on-screen. I think it was probably upon seeing the film that, like many others, I first fell in love with Jack.

The second time was when he opened the door to his house that early evening in April, with the late sun still golden in the sky. “Good evening, ladies,” he said, beaming, and added in a slow drawl, “I’m Jack, and I’m glad you could make it.”

He motioned for us to enter. The front room was low-ceilinged, candlelit, and filled with strangers. There was Greek food, and music playing. I danced with Jack for hours.

And when he invited me to stay the night, I asked Cici what she thought. “Are you kidding?” she said. “Of course!”

In the morning, when I woke up and put on my evening dress from the night before, Jack was already downstairs. Someone I came to recognize later as the screenwriter Robert Towne walked through the front door into the house and looked at me appraisingly as I stood on the upper landing. Then Jack appeared and said, “I’m gonna send you home in a taxi, if that’s okay, because I’m going to a ball game.”

The cab took me back the half hour to the Palisades. When I got out in the backless evening dress, Cici was at the door. She looked at me and just shook her head. “I can’t believe you didn’t insist that he drive you home,” she said. “What are you thinking? If he’s going to take you out again, he must come and pick you up and take you home.”

Jack called a few days later to ask me out. I said, “Yes. But you have to pick me up, and you have to drive me home.” And he said, “Okay. All right. How about Saturday?” And I said, “Okay. But you have to come and pick me up.” Then I got a follow-up call on Saturday saying he was sorry, he had to cancel our date, because he had a previous obligation. “Does that make me a secondary one?” I asked.

“Don’t say that,” he said. “It’s not witty enough, and it’s derogatory to both of us.” I hung up the phone, disappointed. That evening I decided to go out with Jeremy and Kenny Solms and Gail Parent. We were dining at the Old World café on Sunset Boulevard, when they started to whisper and giggle. When I asked what was going on, Gail said, “You were supposed to see Jack tonight, right?” And I replied, “Yes, but he had a previous obligation,” and Kenny said, “Well, his previous obligation is a very pretty blonde, and he just went upstairs with her.”

I took my wineglass in hand and, with heart pumping, climbed the stairs to the upper section of the restaurant and approached Jack’s booth. He was sitting with a beautiful young woman whom I immediately recognized as his ex-girlfriend Michelle Phillips. I had seen them photographed together in magazines when I was living in New York. She was in the group the Mamas and the Papas. As I reached the table, a shadow passed quickly over his face, like a cloud crossing the sun. I lifted my glass airily and said, “I’m downstairs, and I just thought I’d come up to say hi.” He introduced Michelle to me, not missing a beat. She was charming. I guess they were at the end of their relationship at that point. One morning, some weeks later, she drove to his house on Mulholland Drive to collect something she had stored there. Upon discovering that I was with Jack, she came upstairs to his bedroom with two glasses of orange juice. From that moment, we became friends.

* * *

On one of my first dates with Jack, he took me to the races at Hollywood Park. He wore a beautiful cream wool suit with an American flag in rhinestones pinned to his lapel. He got a hard time at the gate to the grandstand for not wearing a tie. Jack gave me fifty dollars’ betting money. I won sixty-seven and returned his fifty.

I was still wrapped up in thoughts of Bob Richardson and the suddenness of our parting. I wrote in a diary I was keeping at the time that I didn’t know what was me and what wasn’t anymore, that I’d been Bob’s possession and his construct, saying the things he might say, even smoking his brand of cigarettes. I thought it must be planetary, all this disruption and indecision. Someone said it was fragments

of helium floating about the atmosphere, because everyone I met at the time seemed touched by a peculiar madness. Even Richard Nixon had lost his moorings and was on his way to being impeached. In the overture to our relationship, Jack sent mixed messages. Alternately, he would ask me to stick around or would not call when he said he would. At one point he told me he had decided that we should cool it, and followed that up with a call suggesting we dine together. Sometimes he called me “Pal,” which I hated. It implied a lack of romantic feeling. I didn’t want to be his crony but, rather, the love of his life. I thought he was still very involved with Michelle, who seemed to have made up her mind to move along.