Water for Elephants (16 page)

Read Water for Elephants Online

Authors: Sara Gruen

But despite bowdlerizing content, my family has been entirely faithful about visiting. Someone comes every single Sunday, come hell or high water. They talk and they talk and they talk, about how fine/foul/fair the

weather is, and what they did on vacation, and what they ate for lunch, and then at five on the nose they look gratefully at the clock and leave.

Sometimes they try to get me to go to the bingo game down the hall on their way out, like the batch from two weeks ago. Wouldn’t you like to join in? they said. We could take you there on our way out. Doesn’t it sound like fun?

Sure, I said. Maybe if you’re a rutabaga. And they laughed, which pleased me even though I wasn’t joking. At my age, you take credit for whatever you can. At least it proved they were listening.

My platitudes don’t hold their interest and I can hardly blame them for that. My real stories are all out of date. So what if I can speak firsthand about the Spanish flu, the advent of the automobile, world wars, cold wars, guerrilla wars, and Sputnik—that’s all ancient history now. But what else do I have to offer? Nothing happens to me anymore. That’s the reality of getting old, and I guess that’s really the crux of the matter. I’m not ready to be old yet.

But I shouldn’t complain, this being circus day and all.

R

OSEMARY RETURNS WITH

a breakfast tray, and when she pulls off the brown plastic lid I see that she’s put cream and brown sugar on my porridge.

“Now don’t you go telling Dr. Rashid about the cream,” she says.

“Why not? I’m not supposed to have cream?”

“Not you specifically. It’s part of the specialized diet. Some of our residents can’t digest rich things the way they used to.”

“What about butter?” I’m outraged. My mind skips back over the last weeks, months, and years, trying to remember the last appearance of cream or butter in my life. Dang it, she’s right. Why didn’t I notice? Or maybe I did, and that’s why I dislike the food so much. Well, it’s no wonder. I suppose we’re on reduced salt as well.

“It’s supposed to keep you healthier for longer,” she says, shaking her head. “But why you folks shouldn’t enjoy a bit of butter in your golden years, I don’t know.” She looks up sharply. “You still have your gallbladder, don’t you?”

“Yes.”

Her face softens again. “Well, in that case you enjoy that cream, Mr. Jankowski. Do you want your TV on while you eat?”

“No. There’s nothing but garbage on these days, anyway,” I say.

“I couldn’t agree more,” she says, refolding the blanket at the foot of my bed. “You give me a buzz if you need anything else.”

After she leaves, I resolve to be nicer. I’ll have to think of a way of reminding myself. I suppose I could wrap a bit of napkin around my finger since I don’t have any string. People were always doing that in movies when I was younger. Wrapping strings around their fingers to remember things, that is.

I reach for the napkin, and as I do I catch sight of my hands. They are knobby and crooked, thin-skinned, and—like my ruined face—covered with liver spots.

My face. I push the porridge aside and open my vanity mirror. I should know better by now, but somehow I still expect to see myself. Instead, I find an Appalachian apple doll, withered and spotty, with dewlaps and bags and long floppy ears. A few strands of white hair spring absurdly from its spotted skull.

I try to brush the hairs flat with my hand and freeze at the sight of my old hand on my old head. I lean close and open my eyes very wide, trying to see beyond the sagging flesh.

It’s no good. Even when I look straight into the milky blue eyes, I can’t find myself anymore. When did I stop being me?

I’m too sickened to eat. I put the brown lid back on the porridge and then, with considerable difficulty, locate the pad that controls my bed. I press the button that flattens its head, leaving the table hovering over me like a vulture. Oh wait, there’s a control here that lowers the bed, too. Good. Now I can roll onto my side without hitting the damned table and spilling the porridge. Don’t want to do that again—they may call it a display of temper and summon Dr. Rashid.

Once my bed is flat and as low as it will go, I roll onto my side and stare out the venetian blinds at the blue sky beyond. After a few minutes I’m lulled into a sort of peace.

The sky, the sky—same as it always was.

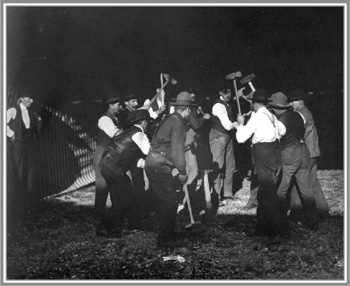

COLLECTION OF THE RINGLING CIRCUS MUSEUM, SARASOTA, FLORIDA

Nine

I’m daydreaming, staring out the open door at the sky when the brakes start their piercing shriek and everything lurches forward. I brace myself against the rough floor and then, after I regain my balance, run my hands through my hair and tie my shoes. We must have finally reached Joliet.

The rough-hewn door beside me squeaks open and Kinko comes out. He leans against the frame of the main door with Queenie at his feet, staring intently at the passing landscape. He hasn’t looked at me since yesterday’s incident, and to be frank, I find it difficult to look at him, vacillating as I do from feeling the deepest empathy for his mortification to being barely able not to laugh. When the train finally chugs to a stop and sighs, Kinko and Queenie disembark with the usual clap-clap and flying leap.

The scene outside is eerily quiet. Although the Flying Squadron pulled in a good half hour ahead of us, its men stand around silently. There is no ordered chaos. There is no clatter of runs or chutes, no cursing, no flying coils of rope, no hitching of teams. There are simply hundreds of disheveled men staring in bafflement at the pitched tents of another circus.

It’s like a ghost town. There is a big top, but no crowd. A cookhouse, but no flag. Wagons and dressing tents fill the back end, but the people who are left mill about aimlessly or sit idly in the shade.

I jump down from the stock car just as a black and beige Plymouth roadster pulls into the parking lot. Two men in suits climb out, carrying briefcases and scanning the scene from under homburgs.

Uncle Al strides toward them,

sans entourage

, wearing his top hat and

swinging his silver-tipped cane. He shakes hands with both men, his face jovial, cordial. As he talks, he turns to gesture broadly across the lot. The businessmen nod, crossing their arms in front of them, figuring, considering.

I hear gravel crunching behind me, and then August appears at my shoulder. “That’s our Al,” he says. “He can smell a city official a mile off. You watch—he’ll have the mayor eating out of his hand by noon.” He claps me on the shoulder. “Come on.”

“Where to?” I ask.

“Into town, for breakfast,” he says. “Doubt there’s any food here. Probably won’t be until tomorrow.”

“Jesus—really?”

“Well, we’ll try, but we hardly gave the advance man time to get here, did we?”

“What about them?”

“Who?”

I point at the defunct circus.

“Them? When they get hungry enough they’ll mope off. Best thing for everyone, really.”

“And our guys?”

“Oh, them. They’ll survive until something shows up. Don’t you worry. Al won’t let them die.”

W

E STOP AT A DINER

not far down the main strip. It has booths along one wall and a laminate counter with red-topped stools along the other. A handful of men sit at the counter, smoking and chatting with the girl who stands behind it.

I hold the door for Marlena, who goes immediately to a booth and slides in against the wall. August drops onto the opposite bench, so I end up sitting next to her. She crosses her arms and stares at the wall.

“Mornin’. What can I get you folks?” says the girl, still behind the counter.

“The works,” says August. “I’m famished.”

“How do you like your eggs?”

“Sunny side up.”

“Ma’am?”

“Just coffee,” Marlena says, sliding one leg over the other and jiggling her foot. The motion is frenetic, almost aggressive. She does not look at the waitress. Or August. Or me, come to think of it.

“Sir?” says the girl.

“Uh, same as him,” I say. “Thanks.”

August leans back and pulls out a pack of Camels. He flicks the bottom. A cigarette arcs through the air. He catches it in his lips and leans back, eyes bright, hands spread in triumph.

Marlena turns to look at him. She claps slowly, deliberately, her face stony.

“Come now, darling. Don’t be a wet noodle,” says August. “You know we were out of meat.”

“Excuse me,” she says, sliding toward me. I leap out of her way. She marches out the door, shoes tap-tapping and hips swaying under her flared red dress.

“Women,” says August, lighting his cigarette from behind a cupped hand. He snaps his lighter shut. “Oh, sorry. Want one?”

“No thanks. I don’t smoke.”

“No?” he muses, sucking in a lungful. “You should take it up. It’s good for your health.” He puts the pack back in his pocket and snaps his fingers at the girl behind the counter. She’s standing at the griddle, holding a spatula.

“Make it snappy, would you? We don’t have all day.”

She freezes, spatula in the air. Two of the men at the counter turn slowly to look at us, eyes wide.

“Um, August,” I say.

“What?” He looks genuinely puzzled.

“It’s coming just as fast as I can make it,” the waitress says coldly.

“Fine. That’s all I was asking,” says August. He leans toward me and continues in a lowered voice. “What did I tell you? Women. Must be a full moon, or something.”

W

HEN

I

RETURN

to the lot, a selected few of the Benzini Brothers tents are up: the menagerie, the stable tent, and the cookhouse. The flag is flying, and the smell of sour grease permeates the air.

“Don’t even bother,” says a man coming out. “Fried dough and nothing but chicory to wash it down.”

“Thanks,” I say. “I appreciate the warning.”

He spits and stalks off.

The Fox Brothers employees who remain are lined up in front of the privilege car. A desperate hopefulness surrounds them. A few smile and joke, but their laughter is high-pitched. Some stare straight ahead, their arms crossed. Others fidget and pace with bowed heads. One by one, they are summoned inside for an audience with Uncle Al.

The majority climb out defeated. Some wipe their eyes and confer quietly with others near the front of the line. Others stare stoically ahead before walking toward town.

Two dwarves enter together. They leave a few minutes later, grim-faced, pausing to talk to a small group of men. Then they trudge down the tracks, side by side, heads high, stuffed pillowcases slung over their shoulders.

I scan the crowd for the famous freak. There are certainly oddities: dwarves and midgets and giants, a bearded lady (Al’s already got one, so she’s probably out of luck), an enormously fat man (could get lucky if Al wants a matching set), and an assortment of generally sad-looking people and dogs. But no man with an infant sticking out of his chest.

A

FTER

U

NCLE

A

L

has made his selections, our workmen tear down all of the other circus’s tents except for the stable and menagerie. The remaining Fox Brothers men, no longer on anyone’s payroll, sit and watch, smoking and spitting wads of tobacco juice into tall patches of Queen Anne’s lace and thistles.

When Uncle Al discovers that city officials have yet to itemize the Fox Brothers baggage stock, a handful of nondescript horses get spirited from one stable tent to another. Absorption, so to speak. And Uncle Al’s not the only one with that idea—a handful of farmers hang around the edges of the lot, trailing lead ropes.

“They’re just going to walk out of here with them?” I ask Pete.

“Probably,” he says. “Don’t bother me none so long as they don’t touch ours. Keep your eyes open, though. It’s gonna be a day or two before anybody knows what’s what, and I don’t want none of ours going missing.”

Our baggage stock has done double duty, and the big horses are foaming and blowing hard. I persuade a city official to open a hydrant so we can water them, but they’re still without hay or oats.

August returns as we’re filling the last trough.

“What the hell are you doing? Those horses have been on a train for three days—get out there on the pavement and hard-ass them so they don’t go soft.”

“Hard-ass, my ass,” replies Pete. “Look around you. Just what the hell do you think they’ve been doing for the last four hours?”

“You used our stock?”

“What the hell did you want me to use?”

“You should’ve used their baggage stock!”

“I don’t know their fucking baggage stock!” shouts Pete. “And what’s the point of using their baggage stock if we’re just going to have to hard-ass ours to keep ’em in shape, anyway!”

August’s mouth opens. Then it shuts and he disappears.

B

EFORE LONG, TRUCKS

converge on the lot. One after another backs up to the cookhouse, and unbelievable amounts of food disappear behind it. The cookhouse crew gets right to work, and in no time at all, the boiler is running and the scent of good food—real food—wafts across the lot.

The food and bedding for the animals arrives shortly thereafter, in wagons rather than trucks. When we cart the hay into the stable tent, the horses nicker and rumble and stretch out their necks, snatching mouthfuls before it even hits the ground.