Authors: Waylon Jennings,Lenny Kaye

Waylon (23 page)

Showin’ out with my brother Tommy on bass.

Afterhours in the late 1960s.

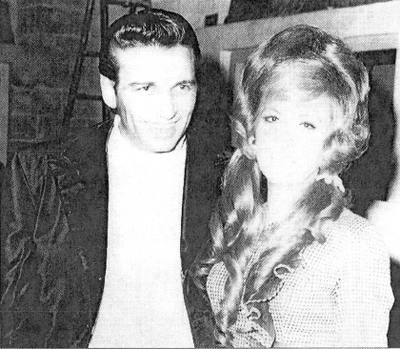

Backstage with Dottie West at Beloit High School, Wisconsin. Which shines more, her hair or my suit?

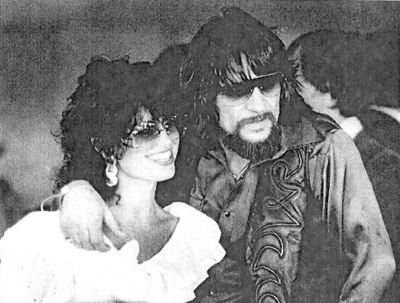

The look of love.

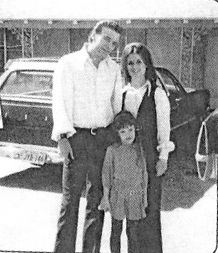

An early snapshot of Jessi, Jennifer, and myself. (

Courtesy Martha Garrisam

)

You sure look sharp wearin’ sunglasses after dark. (

courtesy

The Courier-Journal

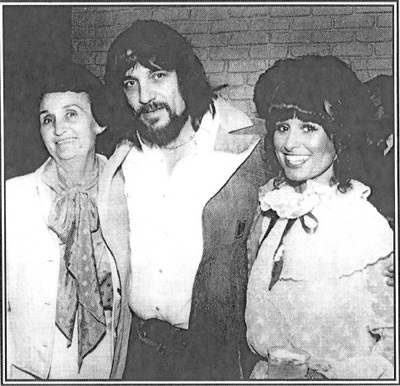

My girls: Momma and Jessi.

He stormed back to where the girl was standing, gave her the finger and a piece of his mind, and strode out of the room. As

soon as he turned that corner, I said, “Girl, let’s get out of here,” and we took off.

The music, the pills, and the women—that was our life on the road. Sometimes I’d screw two or three a night. Richie remembers

me reserving extra rooms in hotels, running up and down the emergency staircase to get from one to the other. Once, in Louisville,

I had girls stashed on three floors. I had been awake for a few days and was determined to visit them all. “Waylon,” he said

to me, “you’re going to kill yourself.” I never knew when enough was enough. Too much was never enough.

I took pills by the fistful. I’d start with a Desoxyn or two, and some little White Crosses, and wash the whole mess down

with an Alka-Seltzer to kick it in the ass. It would come on like gang-busters. Then I’d drink coffee, and every once in a

while I’d pop another to keep going. A doctor once told me that if I took one Desoxyn every day for a month, I’d be a dead

man. I had to laugh. I knew they would kill some people, but they didn’t kill me.

I thought I was invincible. Twenty amphetamines a day was normal, and thirty wasn’t unusual. I’d hit the ground running; I

never had a hangover because I never gave myself a chance. If I would manage to go to sleep at night, I’d put a glass of water

by the bed and about three pills right by the phone. When that wake-up call came, I’d take the pills, lay back down until

they kicked in, and then get up and go. Got to go.

My dad came to the premiere

of Nashville Rebel

in February of 1967. He was real shy, though you could tell he was proud as all get out of me. His neck was so thick, he

found it uncomfortable to wear a tie, but he put one on because it was such an important occasion.

After the movie was over, they had a reception out in the lobby. I caught him as he was trying to slip out the back door of

the theater. He wasn’t used to such crowds in Littlefield. We were stand there talking, and the first person that looked over

and saw him was Tex Ritter. Tex went right up to him. He said, “You’re Waylon’s dad,” and stayed chatting with him all night.

Everybody came over and introduced themselves to him. He was just in glory. I was glad he got to experience that.

Every time I saw Tex do “Hillybilly Heaven” in the movie, I thought of Daddy. When he’s reading from “the big tally book,”

as Will Rogers called it, he moves from greats that have passed on to those whose roll call is yet to come. I couldn’t help

but think my daddy’s name was inscribed in there.

On June 3, 1968, he slipped away, dead of a heart condition. If it was today, there are operations that could’ve given him

another quarter century of being with his family; he was only fifty-three when he passed on. He hadn’t even been sick.

Tommy called me from Nashville. I was in Toronto. “Big brother,” he said. “I got some bad news.”

I knew what it was going to be before he told me. “It’s Daddy, ain’t it?”

I refused to go down to the funeral home and see him. I wanted to remember him as he was. I kind of passed out at the funeral,

and I got a taste of something I’d never seen before, which was people standing around watching other folks’ misery. At the

gravesite, strangers were coming up and wanting autographs. I didn’t know or care who they were.

It took a long time for Daddy’s death to sink in. I thought he’d always be there. When he was alive, I knew I was secure,

that he was the one person who would care for and about me, no questions asked, no matter what. I thought there wasn’t any

trouble he couldn’t help me out of, and after he died, I’ve never felt safe since. It was like he passed over the reins of

the family to me, and I had to take over. “You’re the man of the house now,” I could hear him saying, as if he was going away

for a couple of days leaving me in charge. I kept remembering that day he took on Strawberry Stewart. Even though he had a

hoe in his hand, he dropped it on the ground when he started after him. He only needed himself to be strong.

I’ve never stopped missing him, in all these years, and I like to think I’ve taken his best qualities and passed them along

in my music and life.

Lucky Moeller stepped right in as a surrogate dad for me. He’d had a lot to do with me moving to Nashville in the first place,

even traveling to Phoenix to tell me he could keep me working. He settled me. I’d spend a couple, three nights swarming all

over town, and then I’d pull up at his office. I’d park the Cadillac about four times and almost put it through the front

door. He’d turn off the phone, close the office, and talk to me, about when he used to drive an asphalt truck and when I pulled

cotton.

He had come a long way, from being vice president of a bank in Oklahoma to the head of Moeller Talent, Inc., which he ran

with his son, Larry. Lucky had come to town in the mid-fifties as a personal manager, and with Jim Denny, who ran Cedarwood

Publishing, developed the bulk of offices along Sixteenth Avenue called Music Row. His first love was booking, and with some

thirty artists on his roster, he slotted over thirty-five hundred shows a year.

He booked north and he booked south, west over east, usually in the same week. Moeller Talent had a circuit, locked down and

tight, and once you started, you kept going. They had their White Horses, the top-line acts like Webb Pierce or Kitty Wells

(who once did an incredible 265 one-nighters in 1963); and they might get up to twenty-five hundred dollars a night. But you

had to take all these other people as part of the bargain. If you didn’t pay the big white horse, Lucky still might not cut

you out of the picture.

They would book me into this place, and the owner would stiff me. I wouldn’t get the money, but they could call up Lucky and

get another horse from the stable. Saddle ’em up. You needed to work. Some nights I would only get four hundred dollars. John

Cash took me with him on a couple of tours, but most of it was really rough.

You could only go so far and that was all. The farther I traveled, the farther in the hole I went. I was having to get advances

from RCA to get me transportation. I needed to have something to drive to the shows. I was wearing out cars on a monthly basis.

It was a form of control, to keep us in debt and in their debt. Most of the time we didn’t mind. We were all excited, wide-eyed

and bushy-tailed to be going everywhere, though if we stopped to notice, it was always the same places, the same people, for

the same money. To the Cow Town in San Francisco, down Route 5 through Fresno and Bakersfield to the Palomino Club in L.A.

out in the Valley, then across to Phoenix and J.D.’s, where I was still the biggest thing to hit that town. Around the horn

of Texas where it seemed like I played San Antonio twice a month: the Stallion Club … the Mustang Club … something like that.

They had those big Bob Wills dance floors. That’s what “Bob Wills Is Still the King” is about. I’d get up on the long bandstand,

built for a twelve-piece cowboy orchestra, and I’d be telling my four guys to start spreading out. We’re playing calypso beats,

straight eights, double-timing, and the audience would start looking at me weird. They liked the songs, but they couldn’t

dance to them.

Up to Canada, through the upper Midwest, along the south Atlantic coast, the Virginias and the Carolinas. Every winter we

played a cowboy bar in Jackson Hole, Wyoming. It was twenty-seven below. Then it would be the Gulf Coast in the summer. Or

you’d drive from Minneapolis to Atlanta overnight. I always accused the booking agents of having a dart board with a map on

it.

The band traveled in an old Dodge motorhome. It wasn’t a bus; it had belonged to Red Sovine and had been sitting in his backyard.

Every hose and tire was ready to give up the ghost. One time, going across the Rockies up in Canada, Calgary to Vancouver,

the brakes went out. And I’ll never forget that night in Red Deer, sleet and ice and snow and us under that damn motorhome,

trying to unfuse the push-button transmission, get it in drive so we could keep going forward. But we were still in show business.