Ways of Forgetting, Ways of Remembering (11 page)

Read Ways of Forgetting, Ways of Remembering Online

Authors: John W. Dower

Japanese propaganda presented the Manchurian Incident and the China Incident, as well as the war against the Allied Powers that followed, as legitimate and necessary acts of self-defense. While most of the world outside the fascist camp dismissed this as patently fatuous, within Japan such propaganda was enormously persuasive. There were many reasons why this was so, beginning with Japan's “legitimate rights and interests” on the Asian continent. These privileges rested on a web of formal treaties and agreements dating back to the turn of the century, when Japan first emerged as a modern imperialist power by defeating China (in 1895) and Russia (in 1905). From the moment Japan had been forced to abandon its policy of feudal seclusion in the mid-nineteenth century, the country's leaders had turned to the great, expansionist Western powers themselves for lessons about how to survive and prosper in a fiercely competitive world. The key, they concluded, was “wealth and military power” (

fukoku ky

Å

hei

); and the key to wealth and power, in turn, was to be found in the wisdom of Social Darwinism and “survival of the fittest” thinking.

Realpolitik

and

Machtpolitikâ

pragmatic realism and power politicsâwere the name of the game. This may seem an elemental lesson, but no other non-Western, non-Caucasian, non-Christian country learned itâand practiced itâremotely as well.

More concretely, it became an article of faith among virtually all Japanese that survival and prosperity required both stability in the regions bordering Japan and guaranteed access to the markets and resources of continental Asia. Drawing on the nineteenth-century European and American models of gunboat diplomacy and “unequal treaties,” they used their stunning victories over China and Russia to put the screws to beleaguered China in particular. This adroit marriage of military force and legalistic finesse was how Japan established itself militarily and economically in Manchuria and the rest of China in the first place. (Japan's acquisition of Formosa [now Taiwan] and Korea as colonies, in 1895 and 1910, respectively, was part of the spoils from these early wars.)

When propagandists defended blatant aggression in the 1930s in terms of defending Japan's acknowledged rights and interests, they were thus referring to an elaborate web of treaty rights and concessions they had succeeded in extracting from China over the preceding decades. (The Western powers, including the United States, did not completely repudiate their own unequal treaties with China until the 1940s.) This, however, was but the skin of the propaganda appeal. By the 1930s, most Japanese had become persuaded that the nation was imperiled by events and forces more threatening than anything previously imagined.

One such perceived threat was the warlord politics and domestic chaos that roiled China in the wake of the overthrow, in 1911, of the Manchu dynasty that had ruled the country since the seventeenth century. Another was the birth of Chinese nationalism (popularly known as the May Fourth Movement) that erupted in 1919 in response to great-power manipulations disadvantageous to China at the Paris Peace Conference that followed World War I. It is testimony to how successfully Japan had mastered the power

politics of the West that it sat as one of the victorious nations at this conference, acknowledged as a “great power” alongside the United States, Great Britain, and France. In the crude realpolitik that ignited Chinese nationalism on this occasion, the Western powers essentially endorsed not only their own privileged positions in China, but also additional onerous “rights and interests” Japan had extracted from China shortly after World War I broke out.

All this was compounded by a new threat that went far beyond China per se: the emergence of international Communism in the wake of the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917. By the mid-1920s, Communism had established roots in China and become a potent ideological weapon for mobilizing popular sentiment against “imperialist” encroachment and exploitation. To the very end of World War II in Asia, evocation of the “red peril” remained a staple of Japanese propaganda. Russia had been replaced by the vastly more threatening Soviet Union; Communism was on the rise in China; “red” thought was even percolating into Japan itself.

The collapse of Wall Street in 1929 and the disastrous global depression that followed naturally deepened the sense of impending crisis, particularly since the United States and European countries attempted to protect their own economies by erecting trade barriers against imports from Japan. In this increasingly unstable milieu, Japanese military and civilian planners became obsessed with the concept of autarkyâthe vision of an autonomous and self-sufficient strategic and economic “new order” in Asia, led of course by Japan. The Manchurian Incident and China Incident took place in this atmosphere of acute and protracted crisis. Never had the economic “lifeline” of China seemed more critical to Japanese survival.

When the Western powers condemned Japan's aggressive actions and threw their support behind China, they were denounced as hypocrites: the British, French, Dutch, and Americans, after all, all possessed their own colonies and acknowledged spheres of influence. (Drawing on the Monroe Doctrine, under which the United States laid claim to preeminent rights and interests in

Central America and the Caribbean, Japanese in the 1930s sometimes referred to their own “Monroe sphere” in Asia.) Beyond this, however, the United States and Europe were now seen to be threatening Japan's very ability to survive in a world that seemed to be spiraling into chaos. There was no “world order” any moreâonly international disorder everywhere one looked.

This was a time, moreover, when “yellow peril” sentiment was on the rise in the West. A signal example of this, in Japanese eyes, was the refusal of the new League of Nations to adopt a proposal by the Japanese delegation to include a “racial equality” clause in its founding principles in 1919. The U.S. Congress added insult to injury a few years later, in 1924, by enacting the now notorious “Oriental exclusion” legislation. The Japanese response to such blatant white supremacism was to pump up both antiwhite animus and counterpart paeans to the superiority of the “Yamato race” (a term evoking the mythic divine origins of the Japanese).

Thus, to the Chinese peril of rising anti-Japanese nationalism and the red peril of international Communism, Japanese propagandists added the “white peril” of Western racism, imperialism, and power politics. Japan was engaged in a holy war to defend its very survival as a viable nation and culture.

The lofty rhetoric of holy war (

seisen

) had more than just defensive or reactive connotations, however. The Japanese public had no idea that the Manchurian Incident had been a Kwantung Army plot (this did not become widely known until after the war). On the contrary, the seizure of Manchuria was presented as being not merely a legitimate and necessary response to Chinese provocation, but also an opportunity for enormous creativity. Manchukuo would become a buffer against the spread of Soviet power. It would become a fertile new frontier to which poor Japanese farm families could emigrate. It would become a melting pot for bringing about the “harmony of the five races” (Japanese, Chinese, Koreans, Manchurians, and Mongolians). It would become a pilot project for “constructing a new Asia” free from the scourge of Chinese warlordism and international Communism

and Western imperialismâfree, indeed, from the rapacious and unstable kind of capitalism that had brought about the Great Depression.

When this quest for security and autonomy spilled into China proper, and then into Southeast Asia and the Pacific (to gain access to resources essential to continue the struggle for China), the stakes in the holy war were simply raised to the highest imaginable level. This was madness, as is clear in retrospect, and some Japanese did think this at the time; most of them remained silent, and a small number (mostly members of the Japan Communist Party who refused to recant) were imprisoned. To the great majority of Japanese, however, the holy war was a cause worth dying for. There was, indeed, little alternative.

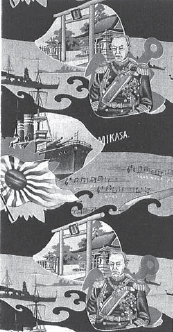

Fig. 3-1. Kimono fabric showing Admiral T

Å

g

Å

Heihachir

Å

. Japan 1934. Printed muslin; 13 ½'' x 23''. Collection Alan Marcuson & Diane Hall, London. Courtesy of Bard Graduate Center: Decorative Arts, Design History, Material Culture; New York. Photographer: Bruce White.

Many commemorative objects were created after the death in 1934 of Admiral T

Å

g

Å

Heihachir

Å

, who was revered for his resounding victory over the Russian navy at both the outset and the end of the Russo-Japanese war. The shrine in the background of this textile design indicates the general's status as a

gunshin

, or military god, after his death.

Like any other people at war, the Japanese mourned their dead while ignoring their victims. Early in the China war, it was common to designate certain of the war dead as

gunshin

, “military gods,” whose sincerity, strength of character, and abiding patriotism exemplified

a pure spirit of sacrifice for sovereign and country. Fittingly for a nation obsessed by the recent history of its struggle for security and stature, the prototype

gunshin

was Admiral T

Å

g

Å

Heihachir

Å

, hero of the victory over Russia in 1905. Although he did not die in combat, T

Å

g

Å

's image was venerated through the course of Japan's fifteen-year war (

Fig. 3-1

).

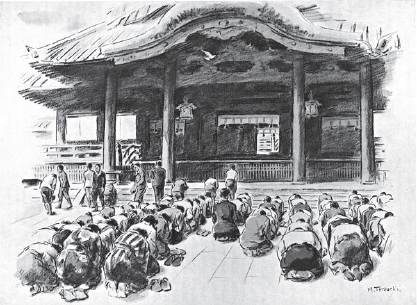

As the China war escalated into the larger “world war” against the Allied Powers, veneration of individual heroes receded before homage to the war dead in generalâall of whom were venerated as

eirei

, or departed heroes. Their names were enshrined in Tokyo's imposing Yasukuni Shrine, a modern (late-nineteenth-century) establishment dedicated to men who, beginning in 1853, had died defending the emperor and imperial cause. (The year 1853 was when the feudal government was forced to open Japan's doors to

the outside world.) When the emperor's subjects visited Yasukuni, they were mourning and thanking all who had made the supreme sacrifice for sovereign, country, and culture (

Fig. 3-2

).

Fig. 3-2. M. Terauchi,

Paying Homage to the Nation's War Dead

, Yasukuni Shrine. Japan, undated. Oil on canvas. From

Reports of General MacArthur

, vol. 2, part 2. Collection National Archives and Records Administration.

“See you at Yasukuni” became the morbidly romantic catchphrase that men prepared to die for the nation were supposed to utter upon taking leave of one another. The cherry blossomâwhich falls from the bough at the height of its beautyâbecame appropriated from ancient texts as the supreme symbol of young patriots perishing in modern warfare. Popular songs, poems, and illustrations propagated this imagery, and it was even said that those who died in the war would be reborn as blossoms on the cherry trees that graced Yasukuni Shrine.

3

As the war drew to its terrible denouement, ideologues and propagandists exhorted the entire populace to fight to the bitter end. “One hundred million hearts beating as one” (

ichioku isshin

), long a favorite slogan for evoking unity, was transformed; the “hundred million,” it was now proclaimed, should be prepared to die “like a shattered jewel” (

ichioku gyokusai

). Death in defense of the holy cause became the ultimate form of purification. Pillage, rape, and the slaughter of others had no place in this dreamworld.

These popular images of purity, heroism, and supreme sacrifice took hold, of course, in a partial vacuum. Just as there was no awareness that the Manchurian Incident had been a Japanese plot, so there was little if any recognition that the Japanese themselves bore grave responsibility for escalation of the China Incident. The atrocities committed by the emperor's soldiers and sailors went unreported at home. Official censorship was abetted by voluntary and ardent self-censorship. The holy war was reinforced by rousing slogans along the lines of

hakk

Å

ichiu

(eight corners of the world under one roof), underscoring Japan's avowed objective of liberating Asian lands from Western domination and bringing them together under an overarching pan-Asian identity. Criticism of the war effortâor, as the years passed, any expression of war weariness or defeatismâwas denounced as lèse-majesté, treasonous behavior that violated the integrity of the august sovereign himself.