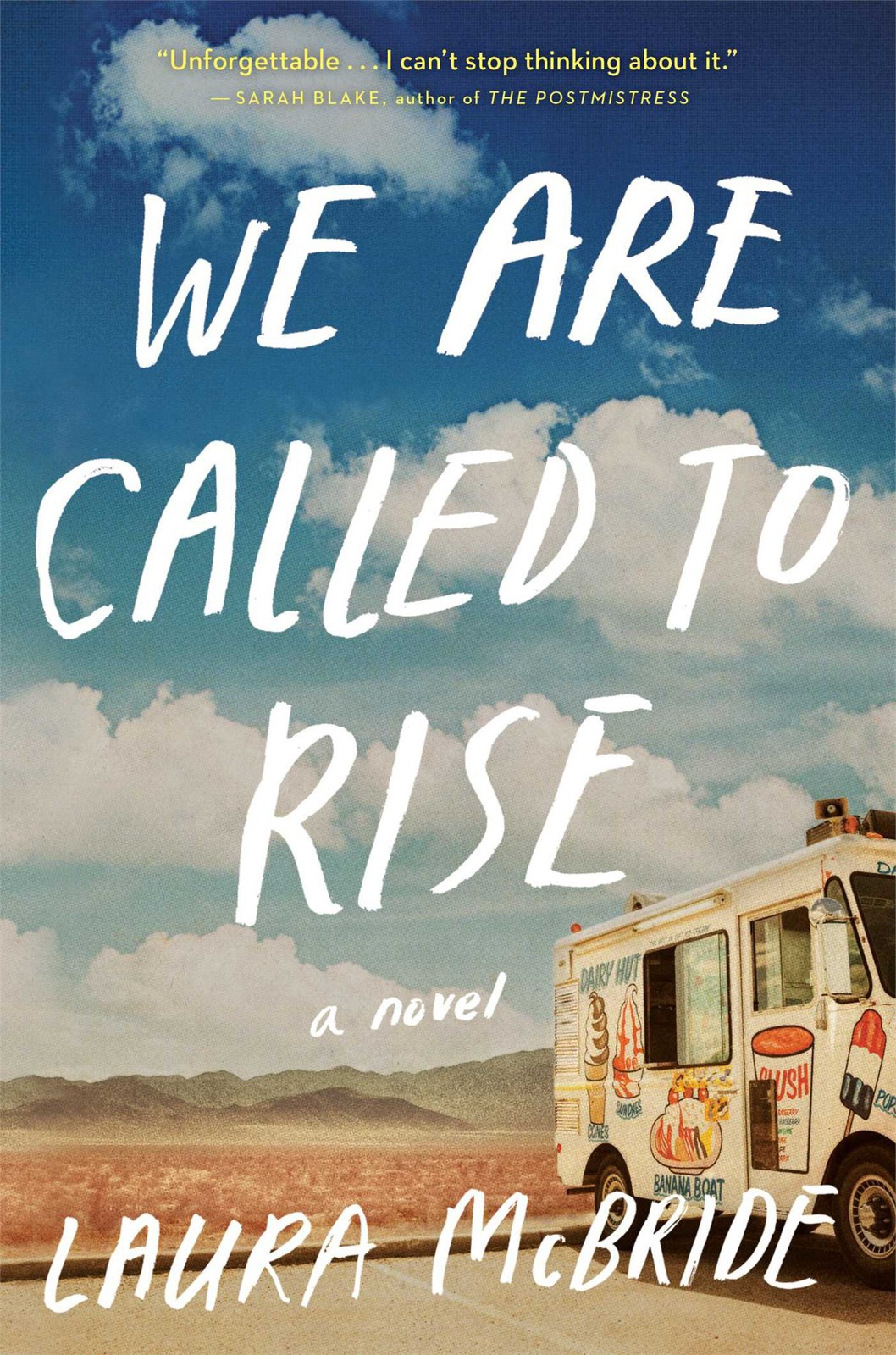

We Are Called to Rise

Thank you for downloading this Simon & Schuster eBook.

Sign up for our newsletter and receive special offers, access to bonus content, and info on the latest new releases and other great eBooks from Simon & Schuster.

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

For Bill Yaffe

and for our children

Leah and Noah

and for our nephew

Stealth

We never know how high we are

Till we are called to rise;

And then, if we are true to plan,

Our statures touch the skies—

—Emily Dickinson

1

Avis

THERE WAS A YEAR

of no desire. I don’t know why. Margo said I was depressed; Jill thought it was “the change.” That phrase made me laugh. I didn’t think I was depressed. I still grinned when I saw the roadrunner waiting to join me on my morning walk. I still stopped to look at the sky when fat clouds piled up against the blue, or in the evenings when it streaked orange and purple in the west. Those moments did not feel like depression.

But I didn’t desire my husband, and there was no certain reason for it, and as the months went by, the distance between us grew. I tried to talk myself out of this, but my body would not comply. Finally, I decided to rely on what in my case would be mother wisdom, or as Sharlene would say, “to fake it till you make it.”

That night, I eased myself out of bed carefully, not wanting to fully wake Jim. I had grown up in Las Vegas, grown up seeing women prance around in sparkling underwear, learned how to do the same prancing in the same underwear when I was barely fifteen, but years of living in another Las Vegas, decades of being a suburban wife, a mother, a woman of a certain social standing, had left me uneasy with sequined bras and crotchless panties. My naughty-underwear drawer was still there—the long narrow one on the left side of my dresser—but I couldn’t even remember the last time I had opened it. My heart skipped a little when I imagined slipping on a black lace corset and kneeling over Jim in bed. Well, I had made a decision, and I was going to do it. I would not give up on twenty-nine years of marriage without at least trying this.

So I padded quietly over to the dresser, and eased open the narrow drawer. I was expecting the bits of lace and satin, even sequins, but nestled among them, obscenely, was a gun. It made me gasp. How had a gun gotten in this drawer?

I recognized it, though. Jim had given it to me when Emily was a baby. He had insisted that I keep a gun. Because he traveled. Because someone might break in. I had tried to explain that I would never use it. I wouldn’t aim a gun at someone any more than I would drown a kitten. There were decisions I had made about my life a long time ago; firing a gun was on that list. But there were things Jim could not hear me say, and in the end, it was easier just to accept the gun, just to let him hide it in one of those silly fake books on the third shelf of the closet, where, if I had thought about it—and I never did—I would have assumed it still was.

How long had the gun been in this drawer? Had Jim put it there? Was he sending a message? Had Jim wanted to make the point that I hadn’t looked in this drawer for years? Hadn’t worn red-sequined panties in years? Had Jim been thinking the same way I had, that maybe what we needed was a little romance, a little fun, a little hot sex in the middle of the kitchen, in order to start over?

I could hear Jim stirring behind me. He would be looking at me, naked in front of our sex drawer. Things weren’t going exactly the way I had intended, but I shook my bottom a little, just to give him a hint at what I was doing.

He coughed.

I stopped then, not sure what that cough meant. I didn’t even want to touch the gun, but I carefully eased the closest bit of satin out from under the barrel, still thinking that I would find a way to slip it on and maybe dance my way back to the bed.

“I’m in love with Darcy. We’ve been seeing each other for a while.”

It was like the gun had gone off. There I was, naked, having just wagged my fifty-three-year-old ass, and there he was, somewhere behind me, knowing what I had been about to do, confessing to an affair with a woman in his office who was almost young enough to be our daughter.

Was he confessing to an affair? Had he just said he was in love with her? The room melted around me. Something—shock, humiliation, disbelief—perhaps just the sudden image of Darcy’s young bottom juxtaposed against the image I had of my own bottom in the hall mirror—punched the air out of me.

“I wanted to tell you. I know I should have told you.”

Surely, this was not happening. Jim? Jim was having an affair with Darcy? (Or had he said he was in love?) Like the fragment of an old song, my mother’s voice played in my mind. “Always leave first, Avis. Get the hell out before they get the hell out on you.” That was Sharlene’s mantra: get the hell out first. She’d even said it to me on my wedding day. It wasn’t the least surprising that she’d said it, but still, I had resented that comment for years. And, look, here she was: right. It took twenty-nine years. Two kids. A lot of pain. But Sharlene had been right.

It all came rushing in then. Emily. And Nate. And the years with Sharlene. The hard years. The good years. Why Jim had seemed so distant. The shock of Jim’s words, as I stood there, still naked, still with my back to my husband, my ass burning with shame, brought it all rushing in. So many feelings I had been trying not to feel. It seemed suddenly that the way I had been trying to explain things to myself—the way I had pretended the coolness in my marriage was just a bad patch; the way I had kept rejecting the signs that something was wrong with Nate, that Nate had changed, that I was afraid for Nate (afraid

of

Nate?); the way that getting older bothered me, though I was trying not to care, trying not to notice that nobody noticed me, trying not to be anything like Sharlene—it seemed suddenly that all of that, all of those emotions and all of that pretending, just came rushing toward me, a torpedo of shame and failure and fear. Jim was in love with Darcy. My son had come back from Iraq a different man. My crazy mother had been right. And my whole life, how hard I had tried, had come to this. I could not bear for Jim to see what I was feeling.

How could I possibly turn around?

I AM NINE YEARS OLD,

and inspecting the bathtub before getting in. I ignore the brown gunk caked around the spigot, and the yellow tear-shaped stain spreading out from the drain; I can’t do much about those. No, I am looking for anything that moves, and the seriousness with which I undertake this task masks the sound of my mother entering, a good hour before I expect her home from work.

“Yep. You sure have got the Briggs girl ass. That’ll come in handy some day.”

She laughs, like she has said something funny. I am frustrated that my mother has walked in the bathroom without knocking, and I don’t want to think about what she has just said. I step in the bathtub quick, bugs or not, and pull the plastic shower curtain closed.

“Should you be taking a bath? What if Rodney walked away?”

“He won’t,” I say, miffed that she is criticizing my babysitting skills. “He’s watching

Gilligan’s Island

.”

“Okay,” she says, and I hear her move out of the bathroom and toward the kitchen. She is going to make a peanut butter and banana sandwich. Sharlene is twenty-seven years old, and she loves peanut butter and banana sandwiches.

“I’M SORRY, AVIS. I NEVER

wanted to hurt you.”

I was still standing naked at the drawer, my back to Jim, the red satin fabric in my hand. I didn’t know what to say to that. I couldn’t seem to think straight, I couldn’t seem to keep my mind on what was happening right that moment. Did Jim just say he was in love with Darcy? Why had I opened this drawer?

And still I was racing toward Jim’s apology, grateful for it, hopeful. One of the first things I ever knew about Jim was that he was willing to apologize.

I AM TWENTY-ONE YEARS OLD,

and working at the front desk of the Golden Nugget casino. It’s taken years to get where I am, years to extricate myself from Sharlene, years to create the quiet, orderly life that means so much to me. That day, Jim is just one more man flirting with the front desk clerk, one more moderately drunk tourist wanting to know if I am free that evening; I barely register that he has said he will be back for a real conversation at four. And, of course, he is not back. But at ten to five, he rushes up, carrying a bar of chocolate, and tickets to

Siegfried and Roy

at the Frontier. I hear his very first apology.

“I’m sorry. I know you thought I wasn’t serious, but I was. I couldn’t get here at four. I was hitting numbers at the craps table, and if I’d left, I would have caused a small riot. Please forgive me. You don’t even have to go to the show with me. You can take a friend.”

That’s how he apologized. All straightforward and a bit flustered and as if he meant it, as if I were someone who deserved better from him.

I WAS WONDERING WHY THE

gun was in the drawer. I was thinking that I would have to turn around. I was acutely aware of being naked. I didn’t know which one of those problems to address first. Turning around. Being naked. Figuring out how the gun got in the drawer. And, of course, none of those were the real problem.

“I didn’t mean to fall in love with her. It just happened. We’ve been spending a lot of time together at work. You’ve been so distant. I don’t know. I didn’t plan it.”

He just kept talking. He seemed to think that I was listening. That he should talk. As if the fact that he didn’t plan it could make it better. He said he was in love with her. Was that supposed to make me feel better? I wanted to get angry—I wanted to grab at the lifeboat of anger—but instead, my mind kept repeating—

cover your ass, where did the gun come from, always get the hell out first, did he say he was in love

—as if I were on some whirling psychotropic trip.

I AM SEVEN YEARS OLD,

and Sharlene and Rodney and I have been living in and out of Steve’s brown Thunderbird for a year. We fill the tank with gas whenever my mom can pick someone’s pocket or Steve can sell some dope, and then get back on the road, driving until we are almost out of gas, until Sharlene sees a place where we can camp without the cops catching us, where there is a park bathroom we can use if we are careful not to be seen. We have criss-crossed the country, even driven into Canada. That was a mistake, because the border patrol might have stopped us. But they didn’t.

The craziest thing about that year in Steve’s car is that there are thousands of dollars crammed under the front seats. Steve has stolen the money, stolen it from a casino, and we are on the lam because he is afraid of getting killed, because he knows the owner of the casino will have him killed the instant he knows where he is, and Steve has decided the bills are marked, that the casino owner—some guy Steve calls Big Sandy—has written down the numbers on the bills and has banks looking for them. So he is afraid to spend any of it, not one dollar of it. Even when we are hungry, even when Rodney cries and cries because his ear hurts, Steve does not give in; he does not spend any of that cash, any of those bills. They sometimes waft up when the car’s windows are open, and Rodney and I try to catch them, and Steve slams on the brakes and swerves the car and screams at us that not one bill can fly out the window.

“AVIS, I’VE BEEN TRYING TO

figure out how to tell you. I didn’t mean for it to be like this. I didn’t mean . . .”

His voice trailed off. He didn’t mean for me to be stark naked and totally exposed when he told me? Then why had he told me?

Oh, yeah, things were about to get awkward.

Awkward if you were in love with your girlfriend.

I lifted my hand to put the bit of satin back in the drawer, and I touched my fingers to the cold, hard metal of the gun barrel. I had never liked guns. I was afraid of them. Afraid of the people who had them.

IT TAKES SHARLENE A LONG

time, all of the year I might have been in second grade, but finally she has had enough. She waits until Steve is passed out stoned, and then she grabs huge fistfuls of the cash under the seats, and she grabs us—I remember being grateful that she had grabbed us, that she had not left us with Steve—and we walk to an all-night diner. We hitch a ride with a truck driver, and after Sharlene and the truck driver are done in the bed in the back of the cab, we get a real hotel room, and a shower. Sharlene stays in that shower until the water goes cold, and each time that the water warms up, she showers some more, and after a night and a day and a night of her showering—with Rodney and me watching television sitting under the pebbled pink comforter, pretending it is a teepee, watching all through the day and the night, whatever shows come on—after that, on the second day, we take a bus, and we are back in Las Vegas.

“WHY IS THERE A GUN

in this drawer?”

It was the first thing I had said since Jim started talking. I realized it must have sounded incongruous. It was the only thing I could make my mouth say.

“What?”

“The gun. Our gun. It’s in this drawer.”

I was still naked. My back was still to him.

“I don’t know. The gun?”

He sounded shaken. He was wondering if I had heard him. He didn’t know what I was talking about.

WE STAY IN A SHELTER

when we first get back to Vegas, where I sleep on a cot near a man who burps rotgut whiskey and we line up for breakfast with a lady who screams that Betty Grable is trying to kill her. After a couple of nights, we move to a furnished motel where Sharlene can pay the rent weekly. That motel is not too far from the motel we lived in before Sharlene met Steve, though it is not the same one we lived in when Rodney was born, and it is not the same one we lived in when Sharlene first came to Vegas—when Sharlene came to Vegas with me, just a baby, and the boyfriend who owned the 1951 Henry J. The Henry J broke down in Colorado, and Sharlene and I and the boyfriend had to hitchhike the rest of the way to Vegas. That’s what Sharlene told me anyway, that’s what I know about how I got to Vegas—that, and that the Henry J was a red car without any way to get into the trunk.

But they were mostly the same, those furnished motels. They all had rats, which didn’t even scurry when I stamped my small foot, and mattresses stained with urine and vomit and blood. In all of them, the neon lights of dilapidated downtown casinos blinked through the kinked slats of broken window blinds.

“THIS GUN USED TO BE

in the closet. Did you put it in this drawer?”

I didn’t know why I was asking these questions. I didn’t care why the gun was in the drawer. I just had to say something, and nothing else that occurred to me to say was possible.