Web of Deceit (33 page)

Myrddion turned his back on Morgan, so he couldn’t be ensnared by those glittering eyes that promised pleasures that equally sickened and excited him. He heard her soft footsteps on the stone floor as she turned, now laughing softly, and swayed off into the shadows of the great circular hall. When he turned back, she was a dark shape disappearing up towards the doors leading out of the council chamber into the growing night.

As Myrddion left the amphitheatre by the opposite set of doors, he tasted salt in his mouth and vomited uncontrollably over the granite steps. Even when his stomach was empty, he continued to retch painfully until he felt light-headed with the voiding of more than just his last good meal.

The trees outside the amphitheatre tilted crazily as he leaned against a pillar. Although full darkness had not yet blanketed Deva and the lamps had not been lit in all the darkening official buildings, an owl leapt into the air out of a copse of hazels in front of him with a clatter of wings and an impression of great eyes and sharp talons.

‘A curse is coming, Grandmother Olwyn. But what can I do? Help me, Mother of us all. Help me to be strong.’

But the blanket of night and something darker that hovered over Deva could not be averted. Wind caused the hazels to shudder and a sudden chill stripped a few more leaves from their branches.

‘All things must end,’ Myrddion whispered, but he had no idea why he spoke such a doom aloud, now that his master was poised on the very edge of success. The skies bled out the last of the day and Myrddion turned wearily towards the banquet hall and the resumption of his duties.

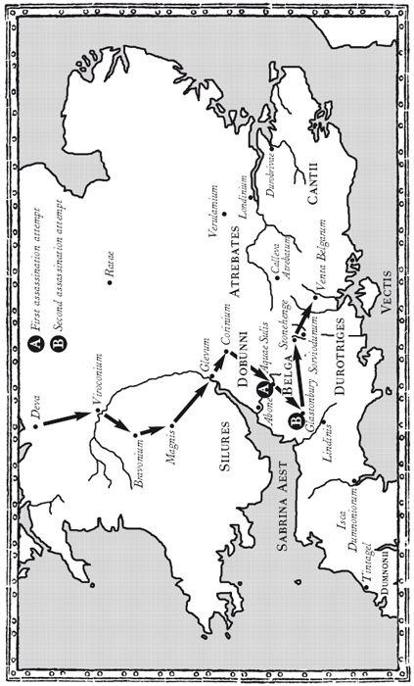

AMBROSIUS’S ROUTE FROM DEVA

Overall, through the regions of earth,

Walls stand rime-covered and swept by the winds.

The battlements crumble, the wine-halls decay:

Joyless and silent the heroes are sleeping

Where the proud host fell by the walls they defended.

Anonymous old English poem,

The Wanderer

The

banqueting

hall was located in the old forum, and as Myrddion approached the merry gathering his eyes were dazzled by the hundreds of lamps, many torches and several fire-pits that warmed the cold stone and lit the dark spaces. A statue of Jupiter, somewhat the worse for wear, presided over the feast from a heavy marble base, while a sculpture of Constantine guarded the exit from the hall. The faces of both sculptures were heavily weathered and Jupiter had lost his nose in some conflict during the latter years of the Roman occupation. Now the crowd of feasting men around their plinths ignored them as if they had never swayed the fortunes of the known world.

Uther greeted Myrddion with an expression resembling good humour.

‘You did a good job in the council meeting, healer. When you started to speak, I considered removing your head from your shoulders just to shut you up, but then you set us all on end. Praise to Mithras, you put that fat fool Lot in his place and scared him silly with the suggestion that he could be under attack. Then, as the final coup, you left every person in the room looking to my brother for guidance. Well done!’

Uther slapped Myrddion on the back with bone-aching force. Surprised, the healer wondered if the prince was already drunk, but decided that Uther’s over-bright eyes and uncharacteristic bonhomie were signs of excitement at being unleashed to kill Saxons along the whole length of the tribal lands.

‘Have a cup of wine, healer. My brother has seen sense and is employing Ulfin as his taster once again, the Pict bitch has been sent back to Venta Belgarum and I only have Pascent to worry about. In short, I’m inclined to be pleased with you.’

Myrddion accepted the finely chased wine cup in the spirit in which it was offered. ‘But is Lord Ambrosius pleased with

me

? As Ulfin no doubt told you, the High King resented my meddling in his affairs, but I’m pleased he is taking some precautions at last.’

‘Ambrosius enjoyed today’s proceedings,’ Uther explained. ‘We’re both in your debt, but don’t worry. You’ll do something to upset me, so consider tonight to be a brief holiday for us both.’

Despite his misgivings and the pall that hung over him after his conversation with Morgan, Myrddion laughed and drank deeply. The heavy red wine warmed his stomach and eased some of the darkness in his thoughts. Servants bustled around the two men, bearing heaped trays of food or heavy wine jugs. The tables groaned under the best fare that Deva could offer, and Myrddion examined the banquet through the eyes of a man who had planned every detail carefully.

In

unusual accord, the kings sat together in geographic groups, for these men would be required to work with each other in defence of the roads and fortresses within their tribal areas. Nor could any king complain about the richness or variety of the food offered for their delectation. Whole geese stuffed with chestnuts, onions, tasty mushrooms and whole boiled eggs vied with every type of fowl, sides of venison, tasty rabbits and haunches of beef. Richly gravied stews swam with mutton, lamb and bacon fat. Bowls of fruit, both fresh and cooked with honey, tempted the heartiest of appetities with sweetness, while the fruits of the sea cooked in pastry or glazed and stuffed with sweetbreads were spread on steaming platters.

But, try as he might, Myrddion could stomach nothing. Perhaps the long day had sucked the hunger out of him. Perhaps he was too weary to eat, having planned this feast for many anxious days. Whatever the reason, the healer drank one cup of wine too many and found his bed early, hoping that a night’s sleep would repair what months of effort had taken away.

Several days passed in argument, eventual accord and feasting. Venonae, Ratae, Lindum, Melandra, Templebrough, Olicana, Verterae, Lavatrae and Cataractonium were apportioned among the tribes, to be manned and strengthened into functioning, efficient fortresses. In the south, Venta Silurum, Durnovaria, Calleva Atrebatum, Portus Adurni and Glevum were selected as towns of major importance which must be garrisoned by warriors who could take offensive action should the need arise. All told, each tribe was made responsible for at least one fortress, including the smaller towers along the two northern walls that would give protection against incursions by the Picts and limit those places where ceols and long ships could find safe harbour.

Much of the argument centred on the fortresses that had already fallen into Saxon, Angle or Jute hands. The consensus was that the Saxons

should be precluded from the use of any lands stolen from the Cantii, but logic ultimately prevailed over sentiment. The expenditure of lives and coin required to retake Verulamium was agreed to be unprofitable, just as the location of Londinium was determined to be too distant to warrant consideration.

‘In any event the land is dead flat in Londinium,’ Uther explained. ‘The Roman fortress on the Tamesis is too small to be of any use to us now, and any attempt to retain control over the city would be a nightmare. While the streets are broad, too many people dwell cheek by jowl in such density that our warriors would be killed in swathes in any attempt to drive the Saxons out. Besides, many tribal traders still dwell there, so the city is not wholly Saxon. In time, perhaps, Londinium might become a neutral city, protected for its trading links with the continent. If you order me, your highnesses, I’ll capture Londinium, but I’d lose it again as soon as I departed to fight another battle elsewhere. Like Verulamium, we’d lose more men than the campaign would be worth.’

‘Then it’s your belief that Londinium and Verulamium are lost?’ Ambrosius said. ‘Is that correct?’

His brother nodded regretfully. Ambrosius pressed home his advantage over the kings as they digested the unpalatable truth.

‘Understand me. We must not trade with the Saxons nor admit foreign merchants into our lands, for so it was that Londinium was originally taken by stealth. Portus Adurni and Magnus Portus will become our trading centres, for Dubris is lost to us. With apologies to our Cantii neighbours, I cannot see any tribal force being able to dislodge the Saxons from those wide, temperate lands of the south. Once again, the landscape is our enemy because of its open, flat terrain. But Anderida must be held, for that fortress exposes Anderida Silva and our southern cities to attack from the barbarians. If the Cantii and Regni tribes are agreeable, the southern coast can still be held.’

Although

many of the kings had never heard of these strange, exotic-sounding places, they caught Ambrosius’s urgency, and so certain key sites became priorities for defensive action by the Britons.

It was soon determined that Anderida, Eburacum, Lindum and Durobrivae were essential to the survival of the united tribes. Piece by piece, an agreement was hammered out, and recorded by the scribes provided by the Christian bishops of the south. Even though many of the tribal kings could not write, they could press their intaglio rings into hot wax or make their marks beside the inscriptions of their names.

From his usual vantage point, Myrddion regretted that the common tongue had no written form, requiring all the records to be translated into Latin. He was unsurprised that so few kings could write, because he understood that many noblemen shared his great-grandfather’s view of literacy. That venerable old king, Melvig ap Melwy, had considered that education weakened a strong man’s mind, his personal resolve and his ability to make decisions. Myrddion’s own education signified that King Melvig considered him disbarred by his illegitimacy from a career as a warrior or a ruler.

Myrddion sighed with regret. Until the kings saw the benefits of learning, they would remain as backward in their thinking as their enemies.

After a week of good food, better wine, carousing and wenching, the kings returned to their own halls secure in the knowledge that someone had taken the helm of the ship of state. They may only be oarsmen on that vessel, but the ship now had a purpose and a direction in which to steer. Myrddion bade them farewell with a feeling of anticlimax. Had it really been so easy?

‘So all our fears were unfounded,’ he commented to Uther as Gorlois, the last king to depart, rode away from Deva towards the southwest. The city was left feeling curiously empty after two weeks of

hustle and bustle as the political centre of the British nation.

‘Thanks to the gods! We’re not out of the woods yet, and we’re still far from home,’ Uther replied. ‘I won’t sleep soundly until we’re back in Venta Belgarum.’

‘So when do we leave?’ Myrddion asked, his voice pitched casually to hide his eagerness to be home.

‘In four days. Ambrosius has taken it into his head to ride to Glastonbury, where he intends to give thanks to all the gods, including the Christian lord. Personally, Glastonbury gives me the horrors. Something old lives in that place. Don’t ask me what it is, because I leave all matters of fancy to you.’

Uther was only half joking. Indeed, he often relegated matters pertaining to religion, superstition or the arcane to the healer for solving. This admission was, of itself, a sign that Uther had relented towards Myrddion. Their truce, fragile as it was, had warmed Ambrosius’s heart, for the High King considered that their cooperation was of significant importance to the safety of the realm.

In the days before they left, Myrddion was kept busy liaising with the city fathers over the future care of the hall while negotiating, in Ambrosius’s name, the payment for outstanding expenses incurred by the tribal kings during their attendance at the moot. While Ambrosius went riding with Pascent and his nobles under the watchful eye of Uther, Myrddion organised the baggage train for their homeward journey, purchased supplies and made arrangements for the scribes to return to Venta Belgarum and their monasteries. There they would produce the master copy of the accord for Ambrosius, along with additional copies for the other kings who had attended the moot.

‘They won’t be able to read it, you know,’ Ambrosius told him one evening over a late-night supper.

‘What they do with the accord doesn’t matter, my lord,’ Myrddion replied. ‘They will be tied even closer to you by the magic

of writing. It’s a simple ploy, I know, but it sets their words in iron, an oath that is not easily broken.’

‘You’re to be congratulated, healer,’ Pascent murmured from his cosy spot near the fire-pit. The nights were becoming chilly, and Pascent’s blue fingers indicated that he felt the cold more than his masters.

‘Why?’ Myrddion asked. Pascent rarely spoke to him, so he was intrigued by the young man’s professed admiration.

‘At the meeting, you tore into the tribal kings for the sole purpose of driving them into Lord Ambrosius’s arms. Truly, a good defence is a powerful attack.’

‘You give me too much credit, Pascent. I merely spoke the truth as I saw it. Honesty can sometimes be a painful thing.’

‘Aye, unvarnished truth can be a knife in the side,’ Pascent murmured in agreement. ‘Kings can rarely afford such a luxury, for subterfuge is their protection and their greatest skill.’