Welcome to Bordertown (15 page)

Read Welcome to Bordertown Online

Authors: Ellen Kushner,Holly Black (editors)

Tags: #Literary Collections, #Body; Mind & Spirit, #Juvenile Fiction, #Fantasy & Magic, #Fiction, #Love & Romance, #Supernatural, #Short Stories, #Horror

“How long since you left the Realm?” I said.

Synack looked up, as if counting hash marks on the inside of her eyelids. “About a year. Jetfuel and I had been writing back and forth, and she sent me the Wikipedia entry on Caer Ceile, which is our family’s estate. It was so weirdly wrong in such an amazing way that I knew I had to come to the World and see it for myself. I’ve been begging my father to let me apply for a visa to leave the Borderlands and go to one of the easy countries, like Lichtenstein or Congo, but he’s worried I’ll get cut up and left in a Dumpster or something. So I can’t get onto anything near low-enough latency to edit Wikipedia in real time.”

“You should try the guest terminal here,” I said. “Most days around two p.m., there’s a thirty-minute window where we get down to about ten microseconds to our next hop, a satellite uplink in North Carolina. We’ll pull something like five K a second then. If you hit Wikipedia with a text-only browser, you should be able to get at least one edit in.”

Her eyes crossed with delight, and it was so cute that I wanted to put a pat of butter on her nose to see if it would melt. “Could I?”

I shrugged, trying for casual (as casual as I could get with this radiant elf princess wafting her croissant smell at me). I was rescued by Jetfuel, who had three handmade cups filled with three handmade cappuccinos, each dusted with a grating of my private reserve of 98 percent cacao chocolate, stuff that was worth more, gram for gram, than gold. I kept it under my mattress. She met my eye and smiled.

Jetfuel sipped her coffee, licked the foam off her lips, and turned to her sister. “Here’s the deal. We’re going to put a number in your luggage, and it will follow you back to Caer Ceile. It’ll be short—less than one K. We’ll put it in your paint box, engraved on one of your brushes. When it arrives, you generate the acknowledgment—use something good for the randomizer, like a set of yarrow stalks—and paint it into the border of a landscape of the fountains. Send it to Dad, a present from his wandering daughter. I’ll copy it off, generate the confirmation, and, well, get it back to you.…” She trailed off. “How do we get it back to her?”

I shrugged. “It sounded like you had it all planned out.”

“Two-thirds planned. I mean, I guess she could put it in a letter or something.”

I nodded. “Sure. We could do the whole thing by mail, if necessary.”

Synack shook her head, her straight ash-blond hair brushing her slim shoulders as she did. “No. It’d never get past the contraband checks.”

“They read all the mail that crosses the Border?”

She shook her head again. More croissant smell. It was making me hungry, and uncomfortable. “No … it’s not like that. The Border …” She looked away, searching for the right words.

“It’s not really directly translatable in Worldside terms,” Jetfuel said. “There’s a thing that the Border does, on the True Realm side, that makes it impossible for certain kinds of contraband to fit through. Literally—it’s the

shape

of the Border; it is too narrow in a dimension that we don’t have a word for.”

I must have looked like I was going to argue. Jetfuel crossed her eyes, looking for a moment

just

like her sister. “This is the part I could never get you to understand, Shannon. Once you cross from the Realm over the Border, you enter a world where

space isn’t the same shape.

Your brain is squashed to fit the new shape, and it can no longer even properly conceive of the idea that the Realm operates on.”

I licked my lips. This was the kind of thing I lived for, and Jetfuel knew it. “So it sounds like you’re saying that it’ll be impossible to do this. Why are you helping me?”

“Oh, I think it’s totally possible. As to why I’m helping you”—she gestured at herself, flapping her hands to indicate her decidedly halfie appearance—“it’s pretty much inconceivable that the Lords of the Realm would ever deign to let a mule like myself through their gate, though it’s technically possible. I am

never

going to get across the Border. I am never going to be able to directly experience that state, the physical and mental condition of being

in

the True Lands. This is the closest I can come.” She looked so hungry, so vulnerable, and I saw for just an instant the

pain she must live with all the time, and my heart nearly broke for her.

Her sister saw the look, too, and she squirmed, and I wondered what it must be like to be the sister who wasn’t an object of shame. Poor Jetfuel.

I dragged the conversation back to technical matters. “So why will the paintbrushes pass? Or the painting?”

Synack said, “Well, the brushes are beautiful. And the painting will be beautiful, too. Plus, it’s poetic, the juxtaposition of the data and the art. It changes their shape. Beauty camouflages contraband at the Border. Ugliness, too.”

I felt my heart thudding in my chest. It must have been the coffee. “That’s the stupidest technical explanation I’ve ever heard. And I’ve heard a few.”

“It’s not a technical explanation,” Synack said.

“It’s a magical one,” Jetfuel said. “That’s the part I keep trying to explain to you. Here in B-town, we get used to thinking of magic as something like electricity, a set of principles you can apply through engineering. It

can

work like that—you can buy a spellbox that’ll power a bike or a router or an espresso machine. But that’s just a polite fiction. We treat spellboxes like batteries, take them to wizards for recharging, run them down. But did you know that a ‘dead’ spellbox will sometimes work if you try to use it for something tragic, or heroic? Not always, but sometimes, and always in a way that makes for an epic tale afterward.”

“You’re telling me that there’s an entire advanced civilization that, instead of machines, uses devices that work only when they’re aesthetically pleasing or dramatically satisfying? Jesus, Jetfuel, you sound like some poet kid fresh out of the World. Magic is just physics—you know that.” I could hear pleading in my own voice. I hated this idea.

She heard it, too. I could tell. She covered my hands with one of hers and gave a squeeze. “Look, maybe it is physics. I think you’re right—it

is

physics. But it’s physics that depends on the situation in another dimension that brains that have been squished to fit into the World can’t think about properly.”

Synack nodded solemnly. “That’s why the Highborn don’t trust Truebloods who were raised here. They’ve spent their whole lives thinking with squished brains.”

Jetfuel took it up again. “And that’s why what we’re doing here is so important! If we can connect both planes of existence, then we can transmit events happening here to the Realm to be viewed with the benefit of its physics! Anyone in the World can use the Realm as a kind of neural prosthetic for seeing and interpreting events!”

I started to say something angry, then pulled up short. “That’s cool,” I said. Both sisters grinned, looking so alike that I had to remind myself which was which. “I mean, that is

cool.

That’s even cooler than—” I stopped. I didn’t really talk much about my idea of using information to lever open the barrier between the worlds. “That is just wicked cool.”

“So how do we get the confirmation back?” Synack said.

Jetfuel finished her coffee. “We start by drinking a lot more of this,” she said.

* * *

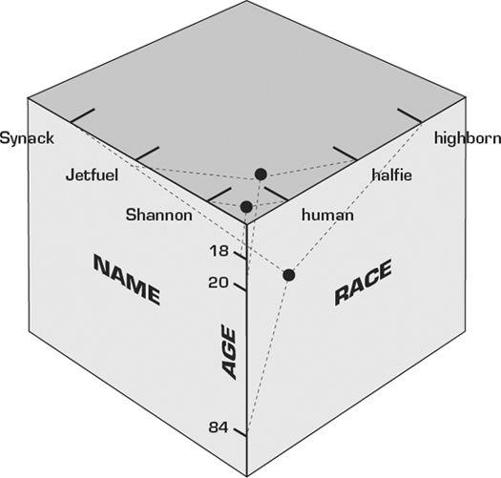

More dimensions are easy. Say you’ve got a table of names and ages:

ShannonJetfuelSynack

201884

If you were initializing this as a table in a computer program, you could write it like this: (shannon,20)(jetfuel,18)(synack,84). We call that a two-dimensional array. If you wanted to add race to

the picture, making it a three-dimensional array, it’d look like this: (shannon,20,human)(jetfuel,18,halfie)(synack,84,highborn). If you were drawing that up as a table, it’d look like a cube with two values on each edge, like this:

That’s easy for humans. We live in 3-D, so it’s easy to think in it. Now, imagine that you want the computer to consider something else, like smell: (shannon, 20, human, coffee)(jetfuel, 18, halfie, bread)(synack, 84, highborn, croissants). Now you have a four-dimensional array—that is, a table where each entry has four associated pieces of information.

This is easy for computers. They don’t even slow down. Every database you’ve interacted with juggles arrays that are vastly more complex than this, running up to hundreds of dimensions—height, fingerprints, handedness, date of birth, and so on. But it’s hard to draw this kind of array in a way that a 3-D eye can transmit to a 3-D brain. Go Google “tesseract” to see what a 4-D cube looks like, but you’re not going to find many 5-D cube pictures. Five dimensions, six dimensions, ten dimensions, a hundred dimensions … They’re easy to blithely knock up in a computer array but practically impossible to visualize using your poor 3-D brain.

But that’s not what Jetfuel and Synack mean by “dimension,” as

far as I can tell. Or maybe it is. Maybe there’s a shape that stories have when you look at them in more than three dimensions, a shape that’s obviously right or wrong, the way that a cube is a cube and if it has a short side or a side that’s slanted, you can just look at it and say, “That’s not a cube.” Maybe the right kind of dramatic necessity makes an obvious straight line between two points.

If that’s right, we’ll find it. We’ll use it as a way to optimize our transmissions. Maybe a TCP transmission that’s carrying something beautiful and heroic or ugly and tragic will travel faster and more reliably. Maybe there’s a router that can be designed that will sort outbound traffic by its poetic quotient and route it accordingly.

Maybe Jetfuel is right and we’ll be able to send ideas to Faerie so that brains with the right shape will be able to see

their

romantic forms and dramatic topologies and write reports on them and send them back to us. It could be full employment for bored elf princes and princesses, shape-judging, like an Indian call center, paid by the piece to evaluate beauty and grace.

I don’t know what I’m going to do with my network link to Faerie. But here’s the thing: I think it would be beautiful, and ugly, and terrible, and romantic, and heroic. Maybe that means it will work.

* * *

The calligrapher was Highborn. Jetfuel assured me that nothing less would do. “If you’re going to engrave a number on a paintbrush handle, you can’t just etch it in nine-point Courier. It has to be

beautiful.

Mandala is the unquestioned mistress of calligraphy.”

I didn’t spend a lot of time up on Dragon’s Tooth Hill, though we had plenty of customers there. The Highborn don’t like Border-born elves, they have very little patience for halfies, they really don’t like humans, and they really,

really

don’t like humans

who came to B-town after the Pinching Off passed. We weren’t poetic enough, we newcomers who’d grown up in a world that had seen wonder, seen it vanish, seen it reappear. We were graspers at wealth, mere businesspeople.

So I had halfies and elves and such who did the business on the Hill.

The calligrapher was exactly the kind of Highborn I didn’t go to the Hill to see. She was dressed as if she had been clothed by a weeping willow and a gang of silkworms. She was so ethereal that she was practically transparent. At first she didn’t look directly at me, ushering us into her mansion, whose walls had all been knocked out, making the place into a single huge room—I did a double take and realized that the

floors

had been removed, too, giving the room a ceiling that was three stories tall. I kept seeing wisps of mist or smoke out of the corners of my eyes, but when I looked at them straight on, they vanished. Her tools were arranged neatly on a table that appeared to be floating in midair but that, on closer inspection, turned out to be hung from the high ceiling by long pieces of industrial monofilament. Once I realized this, I also realized that the whole thing was a sham, something to impress the yokels before she handed them the bill.

She seemed to sense my cynicism, for she arched her brows at me as though noticing me for the first time (and thoroughly disapproving of me) and pointed a single finger at me. “Do you care about beauty?” she said, without any preamble. Ah, that famed elfin conversational grace.

“Sure,” I said. “Why not.” Even I could hear that I sounded like a brat. Jetfuel glared at me. I made a conscious effort to be less offensive and tried to project awe at the majesty of it all.

She seemed to let that go. Jetfuel produced her sister’s paint box and set the brushes down,

click-click-click

, on the work

surface, amid the fine etching knives, the oil pastels, and the pots of ink. She also unfolded a sheet of paper bearing our message, carefully transcribed from a peecee screen that morning and triple-checked against the original stored on a USB stick in my pocket. She had refused to allow me to print it on one of the semi-disposable inkjets that littered the BINGO offices, insisting the calligrapher wouldn’t deign to handle an original that had been machine produced.

The calligrapher looked down at the brushes and the sheet for a long, long time. Then I noticed that she had her eyes closed, either in contemplation or because she was asleep. I caught Jetfuel’s attention and rolled my eyes. Jetfuel furrowed her brows at me, sending me a shut-up-and-don’t-make-trouble look that was hilarious, coming from her. Since when was

Jetfuel

the grown-up in our friendship? I went back to studying my shoes.