Welcome to Your Brain (6 page)

Read Welcome to Your Brain Online

Authors: Sam Wang,Sandra Aamodt

Tags: #Neurophysiology-Popular works., #Brain-Popular works

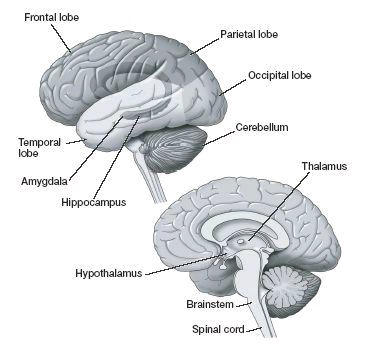

head and eyes, breathing, heart rate, sleep, arousal, and digestion. This stuff is really important, but

you don’t usually notice it happening. A bit higher up, the

hypothalamus

also controls basic

processes that are important to life, but it gets the fun jobs. Its responsibilities include the release of

stress and sex hormones and the regulation of sexual behavior, hunger, thirst, body temperature, and

daily sleep cycles.

Emotions, especially fear and anxiety, are the responsibility of the

amygdala

. This almond-

shaped brain area, located above each ear, triggers the fight-or-flight response that causes animals to

run away from danger or attack its source. The nearby

hippocampus

stores facts and place

information and is necessary for long-term memory. The

cerebellum

, a large region at the back of the

brain, integrates sensory information to help guide movement.

Did you know? Is your brain like a computer?

People have always described the brain by comparing it to the latest technologies,

whether that meant steam engines, telephone switchboards, or even catapults. Today people

tend to talk about brains as if they were a sort of biological computer, with pink mushy

“hardware” and life-experience-generated “software.” But computers are designed by

engineers to run like a factory, in which actions occur according to an overall plan and in a

logical order. The brain, on the other hand, works more like a busy Chinese restaurant: it’s

crowded and chaotic, and people are running around to no apparent purpose, but somehow

everything gets done in the end. Computers mostly process information sequentially, while

the brain handles multiple channels of information in parallel. Because biological systems

developed through natural selection, they have layers of systems that arose for one purpose

and then were adopted for another, even though they don’t work quite right. An engineer

with time to get it right would have started over, but it’s easier for evolution to adapt an old

system to a new purpose than to come up with an entirely new structure.

Sensory information entering the body through the eyes, ears, or skin travels in the form of spikes

to the

thalamus

, in the center of the brain, which filters the information and passes it along, as more

spikes, to the

cortex

. This is the largest part of the human brain, making up a little over three-fourths

of its weight, and it is shaped like a large crumpled-up comforter that wraps the top and sides of the

brain. The cortex originated when mammals first showed up, about 130 million years ago, and it takes

up progressively more and more of the brain in mice, dogs, and people.

Scientists divide the cortex into four parts called lobes. The

occipital lobe

, in the back of your

brain, is responsible for visual perception. The

temporal lobe

, just above your ears, is involved in

hearing and contains the area that understands speech. It also interacts closely with the amygdala and

hippocampus and is important for learning, memory, and emotional responses. The

parietal lobe

, on

the top and sides, receives information from the skin senses. It also puts together information from all

the senses and figures out where to direct your attention. The

frontal lobe

(you can probably guess

where that’s located) generates movement commands, contains the area that produces speech, and is

responsible for selecting appropriate behavior depending on your goals and your environment.

Together, the combination of these abilities in your brain determines your own individual way of

interacting with the world. In the rest of the book, we’ll take these abilities in turn and tell you what’s

known about how the brain accomplishes its everyday tasks.

Fascinating Rhythms: Biological Clocks and Jet Lag

Remember when you were a kid and Uncle Larry bet that you couldn’t walk and chew gum at the

same time? It may have seemed like a lame bet, but when you won his nickel, you were proving

yourself to be a remarkably sophisticated animal.

Walking or chewing demonstrates your brain’s ability to generate a rhythm. Animals can generate

cycles on a wide range of time scales, from seconds (heartbeat, breathing), to days (sleeping), to a

month (menstrual cycles), and even longer (hibernation). All these rhythms are generated by built-in

mechanisms and adjusted based on external events or commands.

Your ability to generate rhythms simultaneously shows that your brain can generate multiple

patterns at once, often independently. Walking involves a tightly coordinated set of events in which

your left leg is instructed to rise, move forward, and then lower, as your body simultaneously moves

forward. Your right leg follows close behind. The sequence of events has to happen smoothly and in

order. These commands are generated mainly by a network of neurons in your spinal cord, all

working together as what’s called a central pattern generator—central because commands originate

here and go to the muscles. This pattern generator can work on its own, since headless cockroaches

and chickens can produce walking movements, but they still need their brains to keep everything

coordinated and to negotiate obstacles. Chewing is driven by another network of neurons distributed

through your brainstem to generate repeated jaw movements. The networks for walking and chewing

can work independently (or together, as Uncle Larry discovered).

Practical tip: Overcoming jet lag

When you travel, the clocks in your body are able to shift by about an hour per day to

reset and get synchronized with the world again. However, you can use your knowledge of

circadian rhythms to help you get over jet lag more quickly. The best way to adjust your

brain’s circadian rhythm is to use light. Melatonin supplements are a distant second. Both

are more effective than simply getting up earlier or later and work better than other tricks

such as exercise. Here are some guidelines for using light and melatonin to help your body

adjust.

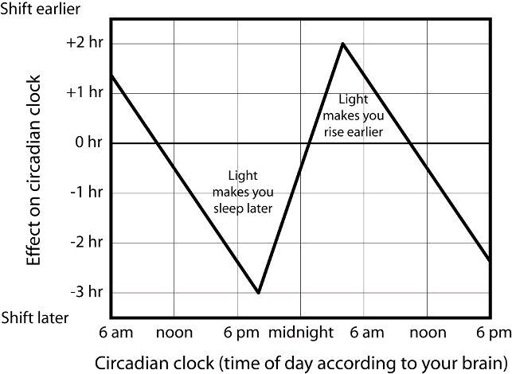

• Get some afternoon light.

The best way to adjust your circadian rhythm is to take a

dose of light when your brain can use it as a signal. Light does different things to your

circadian rhythm depending on the time of day, just as the timing of your push on a swing

affects its movement. In the morning—or, rather, when your body thinks it is morning—light

helps you wake up. Exposure to light at this time will get you up earlier the next day—as if

the light is telling your body that this time is morning. Exposure to light at night, on the other

hand, will get you up later the next day, as if the light is telling your body that the day is not

over yet, so it needs to stay awake longer.

So when you fly east, such as from the Americas to Europe or Africa, you should go

outside to get some bright light a couple of hours before people back home start to wake up.

Finding a source of light is easy at this time because at your destination it is afternoon. This

should help you get up more easily the next day. If you’ve traveled east across eight time

zones or more, try to avoid light first thing in the morning (when it’s evening at home),

because that will push your clock in the wrong direction. Conversely, when you fly west

(from Europe or Africa to the Americas), make sure to get a dose of bright light when you

feel sleepy, before it’s bedtime back at the place where your flight started.

The simple way to remember both these rules is as follows: On your first day at your

destination, get some light in the afternoon. On each subsequent day, as your brain clock

adjusts, get some light two or three hours earlier. Lather. Rinse. Repeat.

• Put out that bedside light!

Enhancing your brain’s built-in morning or evening feeling

is usually easy because it will still be daytime outside when you need the light. However, it

is important to avoid the pitfall of accidentally doing the opposite. Getting light at the

wrong time can set your clock in the wrong direction. So if you can’t sleep at night, don’t

turn on the light! Artificial light is less effective than daylight in setting your clock, but you

should still avoid it.

• For long trips, pick a virtual direction.

If you are doing something really crazy like

going halfway around the world (Bombay to San Francisco, or New York to Tokyo),

decide which way to shift your clock (later each day or earlier each day) and stick with that

plan. For most people, but not all, the easiest thing is to pretend you are going west (through

Chicago or Honolulu) and get that dose of sun in the very late afternoon. Think of it as a

layover for your circadian rhythm.

• When going east, take melatonin at night.

Light exposure produces melatonin with

some time delay, so a pulse of melatonin at night encourages sleep and prepares the next

cycle of your clock. As a result, melatonin is elevated in the body clock’s evening.

Taking melatonin helps a little if done at the right moment of your circadian rhythm. A

dose of melatonin when your body thinks bedtime is soon will help you get up earlier the

next day—and help you get to sleep earlier the next night. At your destination, take it at

nightfall, or even in the middle of the night. However, for reasons that are not known,

melatonin is only helpful if you are going east.

Melatonin’s effect is small, shifting your waking time by up to an hour per day. Exercise

has a similar effect, and should be done at the same time of day. What we don’t know is

whether melatonin or exercise does any additional good beyond the benefit of bright light.

You don’t always realize it, but you’re always falling. With each step you fall forward

slightly. And then catch yourself from falling. Over and over, you’re falling. And then

catching yourself from falling. And this is how you can be walking and falling at the same

time.

—Laurie Anderson, Big Science

Before we get too impressed with ourselves, we should note one more thing: generating repetitive

patterns is a universal feature of animal life. For instance, scientists have studied rhythmic swimming

in lampreys, an odd-looking jawless fish that resembles a long thin sock with a ring of teeth at one

end. Likewise, they study rhythmic chewing in lobsters, which have relatively simple nervous

systems. Lobsters are also interesting because two chewing patterns are directed by a network of only

thirty neurons, which adjust themselves and the connections among them throughout life. (And they

taste great with melted butter.)

Some patterns are automatic, such as your heartbeat or breathing, but these rhythms can still be

controlled. For instance, your heartbeat rhythm, which is generated in your heart itself, can be sped up

or slowed down by commands sent by your central nervous system (see

Chapter 3)

. Your neuronal

network for breathing, which is in your brainstem, can act completely on its own; you don’t normally

think about breathing. It can also be under close control, as when you hold your breath.

A particularly useful rhythm, found in almost every animal that scientists have studied, is the daily

sleep-wake cycle, the circadian rhythm. Circadian rhythms help animals anticipate when light, heat,