Welcome to Your Child's Brain: How the Mind Grows From Conception to College (13 page)

Read Welcome to Your Child's Brain: How the Mind Grows From Conception to College Online

Authors: Sandra Aamodt,Sam Wang

Tags: #Pediatrics, #Science, #Medical, #General, #Child Development, #Family & Relationships

PRACTICAL TIP: HOW TO GET YOUR BABY TO SLEEP

The amount and type of sleep that a child needs is programmed over the course of normal development, without much input from the environment. Triggering sleep is a somewhat different story, one that depends on learning mechanisms.

Babies’ sleep can be made more regular by establishing a regular feeding schedule (see main text). We should warn you that one old-fashioned trick for inducing drowsiness has been shown to backfire. The trick is to add a small amount of alcohol to mother’s milk, for instance, as would occur if Mom has a glass of wine. It is true that this can slightly shorten the time until sleep begins, by about fifteen minutes. The total amount of sleep over the next three and half hours is reduced by an even greater amount, though, suggesting that this is a bad strategy. A better strategy is to watch for drowsiness and act quickly: put the baby down to sleep right away. Babies cycle in alertness, just as adults do, but more quickly.

For bedtime, small children learn quickly to associate particular cues with sleep. Like other associations, children can learn from a single example—or a single exception. Once formed, preferred bedtime habits are hard to break. For example, if children become used to having a parent present at the onset of sleep, that becomes a requirement. It’s better to leave the room so the child associates falling asleep with having the parent absent—which will turn out to be a boon later. In general, establishing a bedtime routine, including toothbrushing, stories, and winding down of attention paid to the child, provides a familiar landing procedure. Consistency is essential. For more information on this subject, an excellent resource is

Healthy Sleep Habits, Happy Child

by Marc Weissbluth.

Night terrors are not simply nightmares. They occur at an age when children’s dreams do not include fear, or for that matter any other emotion (see

Did you know? What children dream about

). In night terrors, the child is fearful but cannot report any specific events. One component could be lack of regulation of brain structures that handle strong negative emotions, such as the amygdala. The amygdala regulates the sympathetic nervous system to mobilize the brain and body to fight or run away. In adults, this system can be suppressed by other regions of the brain such as the hippocampus and neocortex. In children, who have less developed control over their emotional responses (see

chapter 18

), such suppression may not be mature enough to be effective, especially during deep sleep.

DID YOU KNOW? WHAT CHILDREN DREAM ABOUT

Most of us are familiar with the claim, popularized by Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung, that dreams symbolize hidden desires and fears. Perhaps in part because of this culturally driven expectation, we often assign meaning to our dreams after we wake up, making our reports unreliable.

Your child may also experience a version of this coaching if you ever ask what he dreamed about or wish him good dreams. Your wish is harmless, but it also means that you’re inadvertently encouraging storytelling that might not match what was actually dreamed. Unless adults practice recalling their dreams, most of a night’s dreams are forgotten by morning. The same is likely to be true for children.

If you ask adults, they report having a dream 60–90 percent of the time after being woken up from REM sleep, and 25–50 percent of the time from non-REM sleep. They can also report what they were dreaming about. You can take this approach with children too: wake them up and ask what they were dreaming about (or what was happening, if they are very young and do not know what a dream is). If you are unwilling to wake your sleeping child in the name of science, you don’t have to. The sleep researcher David Foulkes and his collaborators stayed up with children between the ages of three and twelve, either in a laboratory or at the children’s homes. They woke the children in the night and then asked what was happening just before they woke up.

At early ages, children’s dreaming was simple and rare. Only 15 percent of three- and four-year-olds reported any dream events after being awoken from REM sleep, and there were no dreams at all during non-REM sleep. The dreams that preschoolers did report were static and often involved animals: “a chicken eating corn” or “a dog standing.” The children themselves typically appeared as passive agents: “I was sleeping in a bathtub.” “I was thinking about eating.” At this age, dreams also lack social interactions or feeling. Preschoolers do not report fear in dreams, nor do they report aggression or misfortunes. This contrasts with their waking lives, in which they can describe people, animals, objects, and events around them.

At later ages, dreams take on more complex qualities. Around age six, dreams become more frequent and acquire active qualities and continuity of events. By eight or nine, dreams are reported as frequently as they are in adults, have complex narratives, and feature the dreamer as an active participant. Dreams also start to include thoughts and feelings.

The static dreams of preschoolers occur when their visual-spatial skills are not fully developed. For instance, children who report more dreams are also better at re-creating pictures of red and white patterns using blocks. At this age, children are also less able to imagine what an object looks like when viewed from a different angle. Such skills depend on the parietal lobe, which sits between neocortical regions that represent vision and space. The parietal lobe does not become fully myelinated until age seven, suggesting that at earlier ages, children may dream in static images because their brains are not fully competent to process movement.

What does this process tell us about child development? One potential answer is that dreams reveal the patterns of brain activity that are possible in the absence of external stimuli. In this respect, they may give you a window into the developing conscious mind of your child.

Night terrors may be triggered by sudden waking. In one study, eighty-four preschoolers who sleepwalked or suffered night terrors were observed while they slept. More than half were found to have disordered breathing, such as obstructive sleep apnea. In this disorder, when respiratory centers in the brainstem receive a signal that breathing has stopped, the sufferer wakes up suddenly, gasping. In children, sleep apnea has several causes, including being overweight and having enlarged tonsils. Remarkably, all the children with sleep apnea who underwent tonsillectomies in that study were cured of their night terrors.

In night terrors and sleepwalking, sleep mechanisms do not fully suppress behaviors that usually occur in waking life. In the other direction, sleep

phenomena can also appear unbidden in the daytime. Examples include narcolepsy and cataplexy, in which an awake person suddenly falls asleep or loses conscious motor control. An upsetting example is sleep paralysis, in which a person wakes up but cannot move. In this case, touching the person is usually enough to end the paralysis. Don’t be reluctant to do this—you will be rescuing your child from anxiety.

Another characteristic of children’s sleep is the need for naps, which is driven by a slow cycle that spans the entire day. In both adults and children, alertness and sleepiness are cyclical. Part of the cycle includes an afternoon lull, followed by a second wind. Until age five or six, the lull is low enough to require an afternoon nap. After that age, children are able to stay up all day, as adults can.

This is not to say that staying awake all day is the best strategy for grownups. Low afternoon alertness in adults may be a remnant of our need for a nap. In one experiment, college students were required to focus on the center of a screen when the letter

T

or

L

flashed, followed after a brief pause by some diagonal bars shown elsewhere on the screen. Students tested early in the day identified both the letter and the orientation of the bars even if they were flashed in quick succession. Later in the day, they needed the letters to be spaced at longer intervals for successful identification. This slowing of perceptual capacities was prevented if the students were allowed to take a brief nap. Naps not only keep toddlers from getting cranky but may also help adults’ mental performance.

So when you watch your baby or child sleeping, be aware that her brain is far from idle. Her brain is fulfilling a well-choreographed process that is coming along nicely without any special effort by her or you. While the sugarplums in her head might not be dancing, bigger things are changing—including events that may restore and rewire the developing brain.

Chapter 8

IT’S A GIRL! GENDER DIFFERENCES

AGES: BIRTH TO EIGHTEEN YEARS

Three-year-olds take gender roles as seriously as drag queens do. One of our colleagues, who was dedicated to freeing her kids from traditional gender expectations, bought a doll for her son and trucks for her daughter. She gave up her quest after she found the boy using the doll to pound in a nail and the girl pretending that the trucks were talking to each other.

Many puzzled parents have wondered where this highly stereotyped behavior comes from, especially in households where Mom wouldn’t be caught dead in a pink frilly dress and Dad would rather cook dinner than watch sports. All over the world, a phase of intense adherence to a sex role seems to be important for the development of a solid gender identity. This stubbornness reminds us of the early stage of grammatical learning, another area where young kids apply newly learned rules more broadly than necessary (“That hurted my foots” instead of “That hurt my feet”).

In light of their behavioral differences, you’d probably imagine that the brains of little boys and girls are distinct in many important ways. Because of our society’s intense interest in sex differences, researchers have done many thousands of studies of this topic, and journalists have been eager to publicize them. This literature is vast and variable, so as we evaluated it, where possible we relied on meta-analysis (see glossary) to evaluate the findings. From careful review of such papers, a few important patterns emerge.

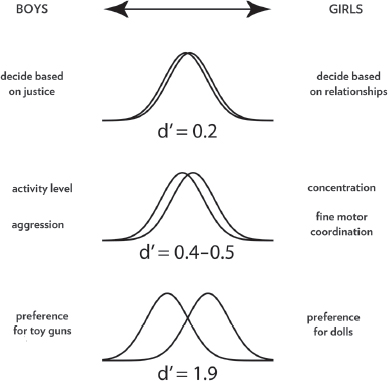

When we evaluate reports of sex differences, it’s important to pay attention to the size of the effects. Most gender differences are too small to matter in

any practical way, and a minority of differences are important when comparing groups. But only a few tell us anything significant about individuals. For instance, girls—on average—are more likely to hear a relatively quiet sound. But it would be impossible to guess whether a particular child is male or female by knowing that child’s hearing ability, because all possible scores are found in both boys and girls. And what’s more, for nearly all sex differences, the differences among individual girls or among individual boys are much larger than the average differences between the sexes, with a few important exceptions.

What do we mean when we say that a gender difference is small or large? Let us be technical for a moment. Scientists often measure the size of a difference between two groups by calculating a statistic called

d-prime (d'

) or

effect size

, defined as the difference between groups divided by the standard deviation, a measure of variability, of one or both groups. If there is no difference, the d' is zero. The d' gets bigger as the size of the difference in average scores between the groups increases, relative to the range of scores within each group.