What Came From the Stars (25 page)

Read What Came From the Stars Online

Authors: Gary D. Schmidt

MELUS: A sweet drink made with something like honey. Tommy said it was like grape juice but a completely different flavor. This isn’t a very helpful description.

MOD: When I asked him what this meant, Tommy pointed to his stomach and said, “Guts.” I don’t know if he meant bravery or his intestines.

NAELI: Fireworks.

NANIG: Not any. I’m not sure if this was really a word in this language or if Tommy was just saying it funny.

NEFER: Never. This is probably another word that Tommy was just saying funny. Sometimes he doesn’t know when to stop. He liked to say it when Patrick Belknap was reaching for his accordion.

NUNC GLAEDRE NON: I think this is a saying. It means something like, “Never again will there be happiness” or “You won’t be seeing good times around here anymore.” This is a depressing language.

NYSSI: Tommy used this to describe a kind of order—so, “in order of

nyssi.”

I never could figure out what this order was. I think it had something to do with color, but I’m not sure.

O’MONDIM: The name of a group of monsters. At least, I think they are monsters. Maybe not.

ORLU: A weapon that you wear at your shoulder. The plural is

orluo,

so I guess adding an

o

in this language is like our adding an

s.

I don’t think Tommy knew how to hold this weapon either.

RAU: A boat. Tommy never said what kind, but it sounds like a boat with a sail.

RECED: A castle. Tommy said that it was built for the Ethelim by the Valorim.

RUCCA: Dirty or ugly or smelly or disgusting. Plymouth Harbor on a really bad day. Or the basement of William Bradford Elementary any day.

RYLIM TIDES: The highest tides that come only twice a year and destroy the

hruntum.

See

hruntum.

SELITH: Relax.

SLYTHING: A sneaky walk, used by the O’Mondim and sometimes Mr. Zwerger in order to catch someone.

SORG: I think this is a certain kind of stone that is very hard and heavy. I asked Tommy if it was like Plymouth Rock, and he said it was a lot harder and heavier than Plymouth Rock, but how would he know that?

STRANG: I guessed “strange” but Tommy gave me a look that said I was an idiot and he said it means “strong.” Then I said it should probably mean “strangle,” and Mr. Burroughs told us to stop.

SYN: After.

THRIMBLE: A technique used in painting—and maybe other arts, but in painting for sure. In this technique, the artist makes things on the canvas move—not appear to move, but really move. Like a goat chewing grass, say.

THRYGETH: The very, very last completed part of a work of art that gives it its power.

TOMBRADISIND: No idea what this means, but it seems important to Tommy. James Sullivan also uses this word. I think it means that something is good. Like, say, “Mr. Burroughs is a

tombra-disind

teacher.” I think.

TREMPE: A loud drum. The plural is

trempo.

TRUNC: Another weapon, this one used by the O’Mondim. It is made out of a gray metal. Its plural is

trunco.

UNFERE: Not beautiful, but not horribly ugly. Somewhere in between, but tending toward the ugly side of things. Sort of like Mrs. MacReady.

VALORIM: The name of another group of people.

VITRIE: A predator that sounds like some sort of reptile, like a dragon. It has talons that sink into you—which sounds very dragony. The plural is

vitrio.

WEGELAS: White birds, sort of like seagulls, but smaller.

WEORULD: Globe or world or planet. Or this could be another word that Tommy was just saying funny.

WUDUO: Long banners that are usually black. They are hung on high walls when someone important has died. Like a president, I guess.

YKRAT: This sounds like a rope made out of something like iron. It is very strong and cannot be broken. I said it could probably also mean “love” and Tommy didn’t say no.

CHAPTER ONE

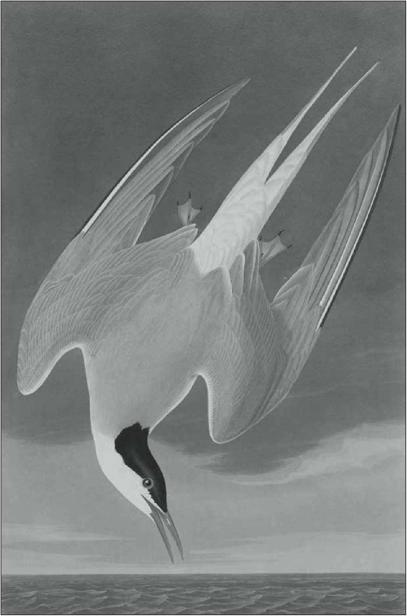

The Arctic Tern

Plate CCL

JOE PEPITONE

once gave me his New York Yankees baseball cap.

I'm not lying.

He gave it to me. To me, Doug Swieteck. To me.

Joe Pepitone and Horace Clarke came all the way out on the Island to Camillo Junior High and I threw with them. Me and Danny Hupfer and Holling Hoodhood, who were good guys. We all threw with Joe Pepitone and Horace Clarke, and we batted too. They sang to us while we swung away: "He's a batta, he's a batta-batta-batta, he's a batta..." That was their song.

And afterward, Horace Clarke gave Danny his cap, and Joe Pepitone gave Holling his jacket (probably because he felt sorry for him on account of his dumb name), and then Joe Pepitone handed me his cap. He reached out and took it off his head and handed it to me. Just like that. It was signed on the inside, so anyone could tell that it was really his. Joe Pepitone's.

It was the only thing I ever owned that hadn't belonged to some other Swieteck before me.

I hid it for four and a half months. Then my stupid brother found out about it. He came in at night when I was asleep and whipped my arm up behind my back so high I couldn't even scream it hurt so bad and he told me to decide if I wanted a broken arm or if I wanted to give him Joe Pepitone's baseball cap. I decided on the broken arm. Then he stuck his knee in the center of my spine and asked if I wanted a broken back along with the broken arm, and so I told him Joe Pepitone's cap was in the basement behind the oil furnace.

It wasn't, but he went downstairs anyway. That's what a chump he is.

So I threw on a T-shirt and shorts and Joe Pepitone's cap—which was under my pillow the whole time, the jerk—and got outside. Except he caught me. Dragged me behind the garage. Took Joe Pepitone's baseball cap. Pummeled me in places where the bruises wouldn't show.

A strategy that my ... is none of your business.

I think he kept the cap for ten hours—just long enough for me to see him with it at school. Then he traded it to Link Vitelli for cigarettes, and Link Vitelli kept it for a day—just long enough for me to see him with it at school. Then Link traded it to Glenn Dillard for a comb. A comb! And Glenn Dillard kept it for a day—just long enough for me to see him with it at school. Then Glenn lost it while driving his brother's Mustang without a license and with the top down, the jerk. It blew off somewhere on Jerusalem Avenue. I looked for it for a week.

I guess now it's in a gutter, getting rained on or something. Probably anyone who walks by looks down and thinks it's a piece of junk.

They're right. That's all it is. Now.

But once, it was the only thing I ever owned that hadn't belonged to some other Swieteck before me.

I know. That means a big fat zero to anyone else.

I tried to talk to my father about it. But it was a wrong day. Most days are wrong days. Most days he comes home red-faced with his eyes half closed and with that deadly silence that lets you know he'd have a whole lot to say if he ever let himself get started and no one better get him started because there's no telling when he'll stop and if he ever did get started then pretty Mr. Culross at freaking Culross Lumber better not be the one to get him started because he'd punch pretty Mr. Culross's freaking lights out and he didn't care if he did lose his job over it because it's a lousy job anyway.

That was my father not letting himself get started.

But I had a plan.

All I had to do was get my father to take me to Yankee Stadium. That's all. If I could just see Joe Pepitone one more time. If I could just tell him what happened to my baseball cap. He'd look at me, and he'd laugh and rough up my hair, and then he'd take off his cap and he'd put it on my head. "Here, Doug," Joe Pepitone would say. Like that. "Here, Doug. You look a whole lot better in it than I do." That's what Joe Pepitone would say. Because that's the kind of guy he is.

That was the plan. And all I had to do was get my father to listen.

But I picked a wrong day. Because there aren't any right days.

And my father said, "Are you crazy? Are you freaking crazy? I work forty-five hours a week to put food on the table for you, and you want me to take you to Yankee Stadium because you lost some lousy baseball cap?"

"It's not just some lousy—"

That's all I got out. My father's hands are quick. That's the kind of guy

he

is.

Who knows how much my father got out the day he finally let himself get started saying what he wanted to say to pretty Mr. Culross and didn't even try to stop himself from saying it. But whatever he said, he came home with a pretty good shiner, because pretty Mr. Culross turned out to have hands even quicker than my father's.

And pretty Mr. Culross had one other advantage: he could fire my father if he wanted to.

So my father came home with his lunch pail in his hand and a bandage on his face and the last check he would ever see from Culross Lumber, Inc., and he looked at my mother and said, "Don't you say a thing," and he looked at me and said, "Still worried about a lousy baseball cap?" and he went upstairs and started making phone calls.

Mom kept us in the kitchen.

He came down when we were finishing supper, and Mom jumped up from the table and brought over the plate she'd been keeping warm in the oven. She set it down in front of him.

"It's not all dried out, is it?" he said.

"I don't think so," Mom said.

"You don't think so," he said, then took off the aluminum foil, sighed, and reached for the ketchup. He smeared it all over his meat loaf. Thick.

Took a red bite.

"We're moving," he said.

Chewed.

"Moving?" said my mother.

"To Marysville. Upstate." Another red bite. Chewing. "Ballard Paper Mill has a job, and Ernie Eco says he can get me in."

"Ernie Eco," said my mother quietly.

"Don't you start about him," said my father.

"So it will begin all over again."

"I said—"

"The bars, being gone all night, coming back home when you're—"

My father stood up.

"Which of your sons will it be this time?" my mother said.

My father looked at me.

I put my eyes down and worked at what was left of my meat loaf.

It took us three days to pack. My mother didn't talk much the whole time. The first morning, she asked only two questions.

"How are we going to let Lucas know where we've gone?"

Lucas is my oldest brother who stopped beating me up a year and a half ago when the United States Army drafted him to beat up Vietcong instead. He's in a delta somewhere but we don't know any more than that because he isn't allowed to tell us and he doesn't write home much anyway. Fine by me.

My father looked up from his two fried eggs. "How are we going to let Lucas know where we've gone? The U.S. Postal Service," he said in that kind of voice that makes you feel like you are the dope of the world. "And didn't I tell you over easy?" He pushed the plate of eggs away, picked up his mug of coffee, and looked out the window. "I'm not going to miss this freaking place," he said.

Then, "Are you going to rent a truck?" my mother asked, real quiet.

My father sipped his coffee. Sipped again.

"Ernie Eco will be down with a truck from the mill," he said.

My mother didn't ask anything else.

My father brought home boxes from the A&P on one of those summer days when the sky is too hot to be blue and all it can work up is a hazy white. Everything is sweating, and you're thinking that if you were up in the top—I mean, the really top—stands in Yankee Stadium, there might be a breeze, but probably there isn't one anywhere else. My father gave me a box that still smelled like the bananas it brought up from somewhere that speaks Spanish and told me to put in whatever I had and I should throw out anything I couldn't get in it. I did—except for Joe Pepitone's cap because it's lying in a gutter getting rained on, which you might remember if you cared.

So what? So what? I'm glad we're going.

After the first day of packing, the house was a wreck. Open boxes everywhere, with all sorts of stuff thrown in. My mother tried to stick on labels and keep everything organized—like all the kitchen stuff in the boxes in the kitchen, and all the sheets and pillowcases and towels in the boxes by the linen closet upstairs, and all the sturdiest boxes by the downstairs door for my father's tools and junk. But after he filled the boxes by the downstairs door, he started to load stuff in with the dishes, stuff like screwdrivers and wrenches and a vise that he dropped on a stack of plates, and he didn't even turn around to look when he heard them shatter. But my mother did. She lifted out the pieces she had wrapped in newspaper, and for a moment she held them close to her. Then she dropped them back in the box like they were garbage, because that's all they were now. Garbage.