What Can I Do When Everything's On Fire?: A Novel (2 page)

Read What Can I Do When Everything's On Fire?: A Novel Online

Authors: António Lobo Antunes

WHAT CAN I DO WHENEVERYTHING’S ON FIRE?

and that’s why, without waking up, I kept thinking

—Why worry I know damned well that I’m

not interested in any episodes I knew weren’t real

—I’m asleep

that might have scared me yesterday, I’m not scared of them now

—Why should I get all worked up if it’s nothing but a lie

aware of the position of my body in the bed, a twist in the sheet under my leg that’s hurting me, the pillow

as usual

sliding between the mattress and the wall, my fingers

by themselves, on their own

looking for it, grabbing it, pulling it up, tucking it under my cheek, which was tucking itself into the pillow in turn, which part of me is pillow and which part is cheek, my arms were holding onto the pillowcase and I was helping my arms

—They’re mine

amazed that they belonged to me, aware of one of the plane trees outside there, a blur on the windowpane at night and day now, getting into my sleep, making me lift up my head

just my head because the twist in the sheet was still hurting me

looking through the window to the office where the doctor was writing out a diagnosis or a report

the desk, the chair, and the cabinet all old, the door always open

where the patients would lie in wait to beg for cigarettes, unshaven, with deadeyes

I could never eat fish eyes in a restaurant, my uncle would stab with his fork and I would be blinded, screaming

they don’t pay any attention to me, nobody ever pays any attention to me, all the orderlies do is shove me along

—Let’s go let’s go

and the fishes sitting on benches, their hands out, begging for cigarettes, my uncle lowering his fork

—Don’t you like eyes, Paulo?

the desk, the chair, the cabinet, the doctor signing something or other, looking at me, quickly picking up his fork, moving it toward the sea bream or the gilthead, I do like eyes, uncle

—You can go home tomorrow

and while I was waking up and a dove was bobbing up and down on a branch of the plane tree, the twist in the sheet stopped hurting, the fish that I am separated itself from the pillow which isn’t me after all, my uncle was amused and retreating into last night’s dream, in which pills had changed into conger eels into puppets, and were asking me for cigarettes

—Don’t you like eyes, Paulo?

the man gasping on my right for example rising up on his mattress like a drowning man on a slow swell, his wife would visit him on Sundays with a small bag of peaches and he would dismiss the peaches which he never finished with a wave of his hand

—Did you bring me any butts, Ivone?

my mother Judite, my father Carlos, the doctor, not this one, a fatter one,

I remembered the doctor’s red necktie when they brought me in, a Gypsy woman who was hollering

or was I the one hollering?

the doctor

—

What’s your mother’s name?

along with that I remembered the attendants, who were holding me by the wrists, from the ambulance Dona Helena had called

—

Take it easy, fellow

all those plates smashed in the kitchen, the pitcher still intact, the hands on the clock keeping watch over the stew

—

Destroy us

maybe it was the attendants who had helped me instead of the fat doctor with the red tie, not in this office but in a room with no windows or a closet where the Gypsy woman or I was hollering or maybe neither one of us, the noise of the dishes

—

What’s your mother’s name?

my mother Judite, my father Carlos

—Did you bring me any butts, Ivone?

five cigarettes on Saturdays but you run out of cigarettes, a chit for a glass of milk at the bar but the milk can’t stand up straight and it spills all over the counter the minute you touch it, the orderly cleans the counter, cleans our jackets and chins with a rag that’s the fossil remains of a towel, the television ranting up on a high shelf

—Damned pigs

cake that crumbles as soon as you bite into it, sandwiches with resistant meat, the cigarette lighted with the tenth match on the filter end as a tiny little flame devours the cotton

—They don’t even notice it, the poor devils

the match goes out too soon or refuses to go out and burns your skin, the certainty that I’d dreamed those days last night or the night before and so why worry since back beyond the day before yesterday, all I can remember is a Gypsy woman hollering and my being strapped down to the bed, by the ambulance attendant maybe

—Take it easy take it easy

the cup I stole from the dish rack smashed on the floor, Dona Helena in tears, I’ve got to break these plates, the pitcher intact, offended

what I liked about the pitcher

asking

—How about me?

the doctor with two or three psychologists or students or customers from the disco where my father worked and the branch of

the plane tree finally quiet as always at noontime, its elbows on the wall pushing back the row of sparrows over its brow, cats in a thicket of thorns or beside the garbage from the dining room where a girl wearing a cap was emptying buckets, the doctor to the students

—They live inside themselves, they have practically no feeling, it’s so hard to help them get to feel again

giving me a basket of peaches no, giving me a cigarette, the match lighting when it should light, going out when it should go out, the ashtray full of ashes and with it like that where can I put my ash, I think Dona Helena’s husband went along with the attendants pointing to the carpet, the floor

—He gets ashes on everything

I think the doctor

They live inside themselves, they don’t even know their own families

and the psychologists or students or customers from the disco who made fun of my father repeating in obedient notebooks they live inside themselves, they don’t even know their own families, the doctor’s wedding ring advancing across the desk,

—See now

the pen tapping on the desk top, waking me up, aware of the position of my body in the bed, of a twist in the sheet under my leg

—Paulo

smashing the pen and the plates in the kitchen, Dona Helena took the pitcher with the line of a break where they’d glued it back together, away from me, the pen still moving along on the desk stopping me from smoking

—Paulo

the second coffin and my pretending not to notice it

—What’s your mother’s name?

and at that point, almost without realizing it, I began to laugh, when my father died I began to laugh just like that, people on long benches, a little old man with a painted mouth and a lap dog in his arms, the second coffin that I pretended not to notice, the priest came out from behind a curtain and I was lying over the casket laughing

—What’s my mother’s name you say, what’s my mother’s name you say?

preventing the psychologists or the students or the customers from the disco from getting a look at the corpse and ridiculing it, my father’s a clown with feathers and spangles and a wig, padding on his behind, his breast, the painted mouth of the old man with the dog bristling at me barking, once I took my father’s mastiff with a bow to Príncipe Real park where they used to play with me on the swing, there were fish in the pond, I never threw cracker crumbs to the fish

—Eat your cracker, Paulo

I unhooked the leash

—Get lost

and the animal was hesitant, hiding under the furniture dribbling piss on the rug, if we’d bought him a glass of milk at the hospital bar he would have spilled it on the counter, my father cleaned the dog’s snout with the rag that was the fossil of a towel, I threw stones at him until I made him disappear around a corner, terrified, confused, the bow was becoming undone and wrapping around his legs, if only I could have thrown stones at my father

—Get lost

until I made him disappear around a corner, the feathers, the spangles, the wig, if only I could have stopped laughing

—They live inside themselves they don’t even know their own families

without a single tear to hide the coffin, the music, the cone of light that was rising up onto the stage and my father singing

not my father, a clown with feathers and spangles and a wig not the clown, a woman, all those plates to smash in the kitchen, the bottles of perfume in his room, the nail polish, the lipsticks, the razor to hide his beard, skirts and more skirts on a clothes rack, if only I could have thrown stones at the…

—What’s your mother’s name?

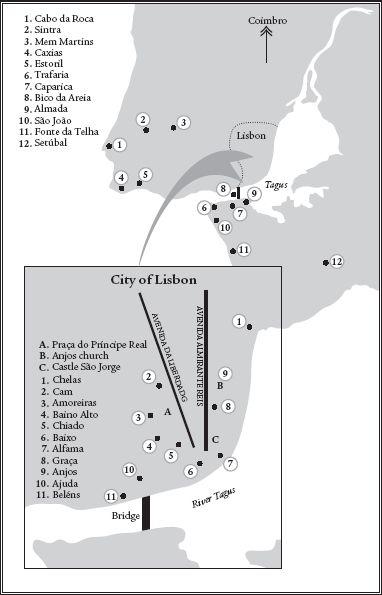

I say, my mother lives in Bico da Areia on the other side of the Tagus, a bus, a second bus, Lisbon upside down in the water, if I knock on the door the leash gets unhooked from my collar and a man on the first step at the entrance, my mother

—Get lost

catching a glimpse of the light on, houses with only tin or wooden roofs, shacks for black people, small gardens with wilted flowers, chestnut trees, in my father’s time the flowers never ended up that way

—Go see if the faggot’s kid is still out there

always fresh flowers in the living room, what’s the reason for your purple fingernails, Father, the painted line that makes your eyebrows, the man came out onto the step chewing, a napkin around his neck and the wilted flowers

—Go see if the faggot’s kid is still out there

the Tagus was going back and forth uncovering the float, that is it seemed to be going back and forth but it was staying right there, the Gypsies’ horses were grazing on dune weeds, I heard a cricket or a night bird by the road, the man with the napkin around his neck wiped his slippers on the step and went back to the table chewing

—Nobody is out there

ruffled curtains, cardboard magnolias, my mother washed pots in the tub in the backyard, not dressed like a bride, barefoot, no pearl tiara on her forehead, my father and she cutting the cake and on top of the cake a pair of wax figurines, I woke up on the mattress in the kitchen as their arguments pulled me out from the bedcovers and I brought the rubber crocodile with me, my mother no longer a bride but not barefoot, not washing pots in the tub in the backyard and emptying the tub into the flower bed, was holding up a bra for my father to see

she kept the pearls in a button box and the figurines from the cake were displayed on the radio

—Do you wear this, Carlos?

my mother’s name was Judite because that time I promised not to tell

when my mother’s eyes looked strange and my uncle pointed at them with his fork

—Don’t you like eyes, Paulo?

the crocodile got away from me and curled around her legs

—Mother

and I was thinking I hope the psychologists or students or customers from the disco didn’t notice, I wonder where the figurines from the cake are, where the string of pearls can be, one of the Gypsies appeared with a switch and drove the horses toward the pine grove, as I curled up under the furniture along with the dog shedding hair and dribbling piss, do you wear this Carlos, and my father not saying anything, throwing stones until I made it disappear around a corner while the crocodile

—Mother

don’t let them leave me all alone when they close the blinds and the man with the napkin

—Judite

not a man, the slices of a man seen through the slats in the blind, they drive me along toward the pine grove with the horses, the crocodile staying stubbornly by the entrance

—Let me stay with you people

explaining to them that I’m not me, I’m not to blame maybe if I grab them around the legs, the slices of my mother getting bigger, half of her glasses looking at the floorboards

—Did you hear the door creak

I thought I could make out the slices of a bottle that went back to being the slices of it placed on the slices of a sideboard, you could hear the pine trees rustling and the river by the float cleaning its teeth with its tongue, the slices of bottle rose up and the man with the napkin appeared on the step with it annoyed and scratching himself

the refrigerator with the dwarf from Snow White on top, the one with the pick on his shoulder who bossed his companions around, the dwarf to my mother