What falls away : a memoir (30 page)

Read What falls away : a memoir Online

Authors: 1945- Mia Farrow

Tags: #Farrow, Mia, 1945-, #Motion picture actors and actresses

« L£

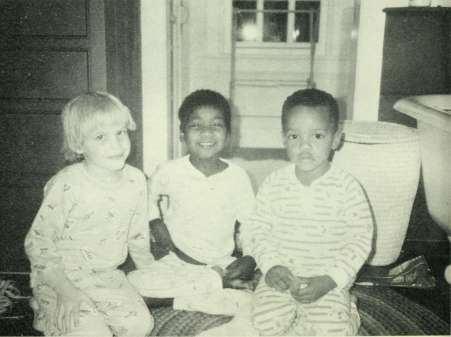

In Ireland tor Widow's Peak with Tarn, Isaiah, and Moses.

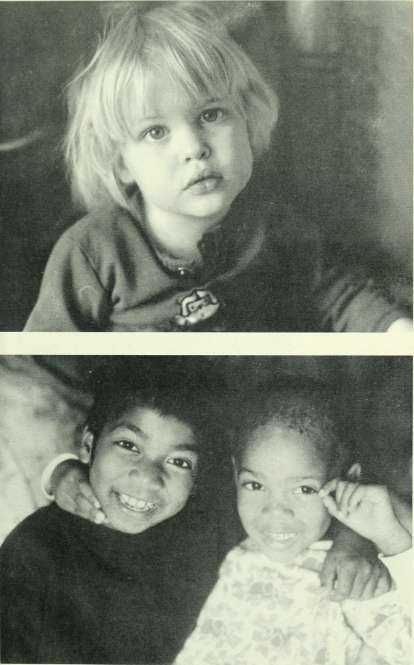

The bovs—Satchel. Thaddeus, and Isaiah—^et readv for bed.

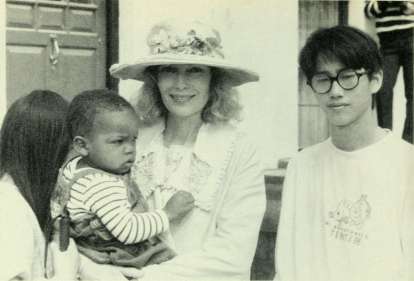

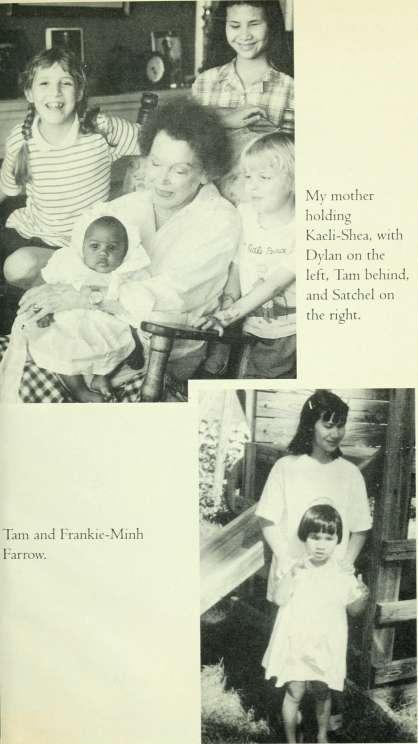

Mv mother holding

Kaeli-Shea, with Dylan on the left, Tarn behind, and Satchel on the n2;ht.

Tarn and Frankie-Mmh Farrow.

The next generation: Lark and Daisy and my first two grandchildren, Sara and Patrick.

Matthew, Lark, Satchel, Daisy, and Tarn at Sascha's wedding.

The screenplay of September was ambitious and problematic. We reshot every single scene as we went along, sometimes four or five times. Woody rewrote major scenes overnight or during lunch, while the cast scrambled to learn the rewrites and to make the long speeches and sometimes ponderous dialogue sound credible and fresh. Fine actors fell by the wayside, including my mother. Parts were recast. There was a shaky feeling in the air. I was relieved when my mother went back with her husband, to the safety of their lives upstate.

When finally the main shoot was over, Woody assembled the footage, looked at it, and threw out the entire thing. Within five weeks he had rewritten the script and we were back at Astoria reshooting the film with a different cast.

As usual I brought Dylan to work, and her crib and toys filled my dressing room. She was now an active toddler who made full use of the long studio hallways. At eighteen months she could sing a dozen songs and speak her mind clearly; she loved being read to and she could identify all the letters of the alphabet. At home and at work she was doted on. And to everyone's astonishment, no one was more doting than Woody Allen.

Woody's parents, the senior Konigsbergs, wintered in Florida, but when they were in New York we dropped by to see them with some of the children every few weeks or so in a ritual that did not vary. Woody would ring their doorbell and then cover the peephole. They always opened it anyway. From the time we walked in until we left a half hour later, he did not address them directly, or sit down or stop mov-mg.

His father was usually watching television when we arrived. Both parents were hard of hearing, as is their son, so the volume was way up.

"You could change the channel and he wouldn't know the difference," said Woody loudly.

"What'd he say?" his mother would ask.

"I don't know," I would answer.

"Can you believe I came from these people?" he said. Of course I could, because he looked exactly like his mother. They seemed like lovely people, but early on things had gone wrong, and Mrs. Konigsberg was always eager to talk about it.

"I don't know," she used to say. "Maybe I was too hard on him when he was young."

"She hit me every day of my life," Woody would call out from wherever he was in the room.

"He was difficult," his mother went on. "Running, jumping, and pulling off his clothes, he was never still. I didn't know how to handle that type of child, he was too active. I was strict with him. Maybe if I hadn't been so strict he would have been different—softer, maybe. Warmer. With his sister it was different, she was an easy child. You could put her down and she would stay there. I was much sweeter with her. Maybe I was too hard on him." Her voice would trail off. She always asked me about my mother, and about each of the children by name. Mr. Konigsberg didn't talk much.

Mrs. Konigsberg passed out chocolate-chip cookies, and with amazement tinged with disapproval, she watched her fifty-two-year-old son romping, cuddling, crawling, and clambering after Dylan.

"It's too much," she'd say to the kids and me as we sat on the sofa eating our cookies, waiting for the half hour to pass. "It's not good for her."

"Twist her nose off," Woody would order Dylan. "She's the wicked witch. Go on, twist it off."

"What'd he say?" his mother would ask.

"Nothing." I'd shake my head. "Dylan, why don't you

come over here and have one of these good cookies? Everybody, careful, don't get chocolate on this white couch."

Woody's response to Dylan was more than I ever imagined. In truth It was much more than I had seen in any father toward a child in my whole life. And Td been married to an Italian, a passionate, emotional guy who was nuts about his daughters; and to Andre, who, when he was there, was an affectionate and demonstrative father. But the most effusive description of Woody Allen could not truthfully include the words passionate, emotional, affectionate, or demonstrative. His reaction to Dylan was a radical departure from his usual behavior. I told myself he'd never really played with a child before, he just didn't know how. Surely he would relax in time.

I had to believe that the participation of the man I loved in the parenting of my child, a situation I had long hoped for, was an answered prayer, a door opening, a new shared, sacred dimension of our lives. And though work remained far and away his priority, by 1987 Dylan was becoming a central consideration in his life. I still hoped his feelings for her would lead to a deeper commitment to the entire family. But not aU of the signs were pointing that way.

He asked me for the key to my apartment. On days we didn't work, he would arrive at about dinnertime. The kids were either in their rooms doing homework or still at the long kitchen table, where the events of the day were related and opinions aired in the liveliest fashion. Our adored housekeeper. Mavis Smith, who had been with the family since 1979, always cooked a terrific meal, and made fresh brownies or chocolate-chip cookies before she left for the evening. Even if Woody and I were planning to go out to dinner later, I served the food and sat with the children.

We'd hear the doorbell's short, loud burst, then the turn of the lock, the heavy slam of the glass-and-wrought-iron

front door, and he was in our kitchen. With barely a nod to me or the other kids, he headed for Dylan. With his mouth wide open, bigger than a grin, his eyebrows high over the black frames of his glasses, it was a face unaccustomed to its own expression—an expression so asymmetrical, large, unguarded, hungry, and foreign, that I would blink to make the strangeness pass, as he scooped Dylan out of her high chair and carried her off into another room.

Woody had been in favor of me adopting another baby when we had talked about it months ago. "The other kids are so much older, it would be good for her to have a playmate, a little sister," he had said, and now I found myself thinking, Surely another baby will dilute this intensity.