Read What Hath God Wrought Online

Authors: Daniel Walker Howe

Tags: #History, #United States, #19th Century, #Americas (North; Central; South; West Indies), #Modern, #General, #Religion

What Hath God Wrought (64 page)

Where Jackson had proposed the federal government should define and exclude “incendiary” materials from the mail, Calhoun introduced a bill in the Senate to require the federal Post Office to enforce whatever censorship laws any state might enact. At one point in its consideration, Vice President Martin Van Buren saved this measure by his casting vote, but eventually Calhoun’s proposal was defeated. Seven slave-state senators, including Henry Clay and Thomas Hart Benton, joined with northerners to vote it down. Concern for civil liberties, even those of unpopular minorities, counted for more in the halls of Congress than within the Jackson administration. In 1836, an opposition representative from Vermont named Hiland Hall persuaded Congress to pass a law affirming the responsibility of postmasters for delivering all mail to its destination.

42

In practice, however, Kendall found ways to allow southern postmasters to continue deferring to the censorship laws of their states. As he put it in a letter to the Charleston postmaster, “We owe an obligation to the laws, but a higher one to the communities in which we live.” What Calhoun and Van Buren would have required, Kendall and his successors managed to permit. And as Jackson had foreseen, no southern addressee—no matter how respectable, moderate, or Jeffersonian—dared challenge the policy and demand his mail. Instead, the prominent men whom the abolitionists had targeted led public meetings across the South, demanding the Post Office ban abolitionist mailings, and often demanding as well that northern states crack down on their antislavery societies.

The southern practice of ignoring inconvenient federal laws in order to preserve white supremacy was established long before the Civil War. Jackson, who had stood up to South Carolina so firmly over the tariff, cooperated with the state’s defiance of federal law when the issue was race.

43

The refusal of the Post Office to deliver abolitionist mail to the South may well represent the largest peacetime violation of civil liberty in U.S. history. Deprived of access to communication with the South, the abolitionists would henceforth concentrate on winning over the North.

V

April 8, 1834, was the first of three days of voting in a hotly contested race for mayor and city council of New York. The Bank War, then at its height, inflamed partisan rancor. In the predominantly Democratic Sixth Ward, armed men drove the Whig Party observers away from the polling place. The next day a Whig parade was attacked when it passed through the Sixth Ward. The coverage of these events by the local partisan press exacerbated passions rather than encouraging order. The Whigs resolved to challenge the Democratic “bullies” who for years had intimidated prospective voters, helping keep the city under the control of Tammany Hall. On the third day of voting, the rioting involved thousands; the mayor himself was clubbed to the ground as he tried to restore order; and only the mobilization of twelve hundred soldiers separated the antagonists. The election returned a Democratic mayor (by 180 out of 35,000 votes cast) and a Whig council. Although many were injured in the disorders, only one person had been killed, probably because the riot was halted just as the participants began to arm themselves with guns.

44

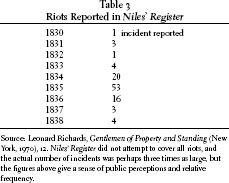

The April election riot commenced a year of recurrent mob violence in New York City and heralded an explosion of such violence across the whole United States for the next three years. In August 1835, at the peak of the disorders, the

Richmond Whig

deplored “the present supremacy of the Mobocracy,” while the Philadelphia

National Gazette

declared, “Whenever the fury or the cupidity of the mob is excited, they can gratify their lawless appetites almost with impunity.”

45

Party politics was by no means the only cause of rioting in Jacksonian America. Ethnic, racial, and religious animosities provided the most frequent provocation to riot. The growing cities seemed vulnerable to anyone exploiting group resentments among the increasingly diverse urban communities, though small settlements certainly demonstrated their share of mob violence, as the Mormons found out in Missouri and Illinois. The absence of effective law enforcement in both urban and rural areas permitted inflammatory situations to get out of hand. The largest riots, surprisingly, were those directed against theaters where prominent British actors accused of anti-American remarks were performing. New York City appearances by actor Joshua Anderson were repeatedly called off in 1831–32, despite audiences paying to see him, because of unchecked violent demonstrations by self-styled patriots seeking excitement. Other actors subjected to the same treatment included Edmund Kean and William Charles Macready. The worst of many riots of this kind occurred in 1849 at the Astor Place Opera House in New York, in which as many as thirty-one people may have died.

46

Rioting, rather than crime by individuals, primarily precipitated the creation of police forces as we know them. There were no professional city police forces before 1844, when New York began the process of creating one in imitation of London’s, founded by Sir Robert Peel in 1829 (hence called “Bobby’s” or “bobbies”). In pre-police days, the only recourses of beleaguered officials consisted of night watchmen (primarily looking out for fires), courtroom marshals, a few part-time, politically chosen constables, ad hoc sheriff ’s posses, and the military. Uniforms for the new police forces were introduced only slowly, beginning in the 1850s, because many in America felt they smacked of militarism.

47

The nickname “copper” or “cop” came from the copper badges that antedated uniforms.

The most common targets of mob violence in the 1830s were the abolitionists and the free black communities that supported them. In fact, the appearance of organized abolitionism explains much of the dramatic rise in the number of riots. In October 1833, an elite-led mob forced the prominent evangelical philanthropists Arthur and Lewis Tappan to relocate the founding meeting of their New York Anti-Slavery Society. New Yorkers, with so much of their city’s business dependent upon the cotton trade, felt understandably suspicious of interference with southern slavery. Even members of the American Colonization Society, offended by the uncompromising rhetoric of the abolitionists, joined the mob. After intimidating the abolitionists into a change of venue, the crowd conducted their own meeting according to rules of order.

48

The great abolitionist undertaking of 1835, their mass mailing of pamphlets to southern addresses, provoked the largest number of riots. The communications revolution, by empowering social critics on the one hand and fanning conservative fears on the other, catalyzed the violence. Future president John Tyler, addressing an antiabolition crowd at Gloucester Courthouse, Virginia, in August 1835, focused his remarks on the sensationalism of the antislavery tracts, their wide circulations, and “the cheap rate at which these papers are delivered.” He pointed with horror to the novel involvement of women in the abolitionist movement, particularly in the circulation of mass petitions, and to the “horn-books and primers” aimed at “the youthful imagination.” Tyler viewed the abolition crusade as an assault not only on slavery but on the entire traditional social order. Not only in the South, but even in the North, the early antiabolitionist mobs sometimes enjoyed the respectable leadership of “gentlemen of property and standing” like Tyler.

49

On October 21, 1835, such a mob in Boston almost killed William Lloyd Garrison; the mayor of the city saved his life by locking him up in jail. Two years later, an abolitionist editor named Elijah Lovejoy was not so fortunate; he died defending his press against a mob in Alton, Illinois. Lovejoy remained the only abolitionist killed in the North; he was shot after killing one of his assailants. The editor became a martyr to his cause, and his death was held up as a shameful interference with free speech. Thereafter respectable opinion in the North swung away from mob action, whether against abolitionists or others.

The 1830s witnessed a transition in the composition of mobs from elite-led, politically motivated, and relatively restrained collective actions to impromptu violence, sometimes perpetrated as much for the sheer venting of emotion as for any planned objective, in which people were more likely to be injured or killed.

50

In the summer of 1834, the newer, less restrained, kind of mobs spread a more awesome terror in New York City. African American celebrations of the seventh anniversary of the end of New York slavery on July 4, 1827, triggered a massive reaction. For three days and nights starting on July 9, mobs vandalized, looted, and burned the homes, shops, and churches of the free black community and white abolitionists. More than sixty buildings were gutted or destroyed, six of them churches, including St. Philip’s African Episcopal Church on Centre Street. Only when it looked like the rioters would turn on the property of the wealthy in general did Democratic mayor Cornelius Lawrence (the one elected by 180 votes) instruct the militia to get serious about enforcing the law. “As long as Negroes and a few isolated white men were the targets, he had not cared,” one historian has observed.

51

The local press too experienced a change of heart, and suddenly deplored the violence it had earlier shamelessly exacerbated. The rioters seem to have been largely working-class whites motivated (so far as one can tell) by fears of racial intermarriage and black competition for jobs, education, and housing.

52

The most notorious of 1834 riots, the burning of the convent at Charlestown, Massachusetts, seems to have been an example of the old-fashioned kind of rioting; it involved both middle-class and working-class conspirators and spared the persons of the sisters. Increasingly, however, mob violence expressed the varied discontents of the working classes. Many of the other disturbances of 1834 document the shift. In January, near Hagerstown, Maryland, Irish canal workers from County Cork fought against other Irish canal workers from County Longford, and dozens died before troops arrived from Fort McHenry. The next month, two volunteer fire companies in New York City engaged each other in a pitched battle. In April, a Democratic Party mob looted the branch of the BUS in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. Philadelphia suffered a race riot in August, prompted by white workers’ fears of blacks taking their jobs, followed by an election riot in October. Elsewhere Protestant workingmen attacked Catholic immigrants. November saw forty Irish immigrant workers laying track between Baltimore and Washington for one of the newly invented locomotives attack their supervisors and kill two of them in an action with both ethnic and class dimensions.

53

Workingmen in Baltimore rioted in August 1835 against the defunct Bank of Maryland, ruined by the speculations of Taney’s crony Thomas Ellicott, of which many had been depositors or creditors. While their action expressed understandable feelings, it only delayed winding up the bank’s affairs (and provoked bitter condemnation from Taney, who was no friend of the working class).

54

An acute analysis of rioting in this period concludes that although immigrant and working-class groups had plenty of legitimate grievances, their rioting was frequently counterproductive and more often than not misdirected against scapegoats.

55

Frontier vigilantes enforced a venerable version of quasi-respectable violence in America. Vigilantes conceived of their violence as a supplement to, rather than a rebellion against, the law. The vigilante tradition did not die down as soon as an area became settled; in 1834, a mob in Irville, New York, took direct action against prostitution. But the heightening level of violence in vigilantism shocked observers. A mob in St. Louis lynched a black man accused of murder by roasting him over a fire in 1835. The same year, when the people of Vicksburg, Mississippi, decided to rid their town of gamblers, instead of riding the culprits out of town on a rail, they hanged them—along with several other outsiders who were simply in town on business.

Southerners seemed readier to resort to violence, inured as they were to it by the beatings and other brutal punishments routinely inflicted by masters, overseers, and slave patrols. Many riots of the antebellum era manifested the southern attempt to stifle criticism of slavery, just as so many riots of the postbellum era reflected southern determination to keep the freedpeople in subjection. (Vicksburg would become the site of one of the most notorious race riots after the Civil War.) Another category of mob was peculiar to the South: those generated by fear of slave insurrections, real or imagined. Not only did the slave states generate more mobs, their mobs attacked persons more than property, and in consequence killed more people. In the peak year of 1835, the seventy-nine southern mobs counted by historian David Grimsted killed sixty-three people, while the sixty-eight northern mobs killed eight.

56

And in the South, the legal authorities showed even less capacity or interest in controlling mob violence.