What If Ireland Defaults? (10 page)

Read What If Ireland Defaults? Online

Authors: Brian Lucey

Stiglitz, J. (2000) âCapital Market Liberalization, Economic Growth, and Instability',

World Development

, Vol. 28, No. 6, pp. 1075â1086.

Stiglitz, J. (2001) âFrom Miracle to Crisis to Recovery: Lessons from Four Decades of East Asian Experience', in J. Stiglitz and S. Yusuf (eds.),

Rethinking the East Asian Miracle

, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 509â526.

Stiglitz, J. (2002)

Globalization and Its Discontents

, New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

Stiglitz, J. (2004) âCapital Market Liberalization, Globalization, and the IMF',

Oxford Review of Economic Policy

, Vol. 20, No. 1, pp. 57â71.

Stiglitz, J. (2006)

Making Globalization Work

, New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

Stiglitz, J. (2010a)

Freefall: America, Free Markets, and the Sinking of the World Economy

, New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

Stiglitz, J. (2010b) âContagion, Liberalization, and the Optimal Structure of Globalization',

Journal of Globalization and Development

, Vol. 1, No. 2, Article 2.

Stiglitz, J. (2010c) âRisk and Global Economic Architecture: Why Full Financial Integration May Be Undesirable',

American Economic Review

, Vol. 100, No. 2, pp. 388â392.

Stiglitz, J. (2011) âPreface', in D. Coats (ed.),

Exiting from the Crisis: Towards a Model of More Equitable and Sustainable Growth

, Brussels: European Trade Union Institute, pp. 9â16.

Stiglitz, J. and Weiss, A. (1986) âCredit Rationing and Collateral', in J. Edwards, J. Franks, C. Mayer and S. Schaefer (eds.),

Recent Developments in Corporate Finance

, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 101â135.

United Nations Commission of Experts of the President of the United Nations General Assembly on Reforms of the International Monetary and Financial System (2010)

The Stiglitz Report: Reforming the International Monetary and Financial Systems in the Wake of the Global Crisis

, New York: The New Press.

Wagner, W. (2010) âDiversification at Financial Institutions and Systemic Crises,'

Journal of Financial Intermediation

, Vol. 19, No. 3, pp. 373â386.

Wall Street Journal

(2010) âIreland's Fate Tied to Doomed Banks',

Wall Street Journal

, eastern edition, 10 November 2010.

Wall Street Journal

(2011) âIreland's Banks Get Failing Grades',

Wall Street Journal

, eastern edition, 1 April 2011.

Debt Restructuring in Ireland: Orderly, Selective and Unavoidable

Constantin is adjunct professor at the School of Business, Trinity College Dublin, and a director of St Columbanus AG, a Swiss asset management company. An internationally syndicated newspaper columnist, he blogs at

trueeconomics.blogspot.com

.

Ireland's Road to Debt Restructuring

In a 2011 research paper titled âThe Real Effects of Debt', Bank for International Settlements (BIS) researchers S. Cecchetti, M. Mohanty and F. Zampolli provide analysis of the long-term effects of debt on future growth. The authors use a sample of eighteen Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD) countries, not including Ireland, for the period of 1980â2010 and conclude that âfor government debt, the threshold [beyond which public debt becomes damaging to the economy] is in the range of 80 to 100% of GDP [gross domestic product].' The implication is that âcountries with high debt must act quickly and decisively to address their fiscal problems.' Furthermore, âwhen corporate debt goes beyond 90% of GDP, [the] results suggest that it becomes a drag on growth. And for household debt, ⦠a threshold [is] around 85% of GDP.' Combined private non-financial and public debt in excess of circa 250 per cent of GDP exerts a long-term drag on future growth.

These effects were present during the benign environment of the Age of Great Moderation, the period from the mid-1990s through 2007, when low inflation and cost of capital spurred above-average global growth. More significantly, the effects were present while the Baby Boom generation was at its prime productive age, rapid expansion of information and communication technology (ICT) drove productivity in manufacturing and services, and innovations in logistics revolutionised retailing (the so-called Wal-Mart effect).

In other words, despite all the positive push forces lifting the growth rates the negative pull force of building debt overhang was still econometrically traceable. Eurozone economies posted average growth rates of 2.0 per cent per annum in 1991â2007, well below the less indebted group of smaller advanced economies

1

that posted average annual growth rates of over 4.2 per cent.

2

From the Irish perspective, the impact of debt overhang on long-term growth in the advanced economies presents a clear warning. Ireland's robust growth in the 1990s and through to 2007 represents not a long-term norm but a delayed catching up with the rest of the advanced economies. In other words, even disregarding the negative effects of the severe debt overhang we experience today, Ireland's average growth rates in the foreseeable future will be close to the average growth for smaller open economies in the Eurozone. That rate, according to the IMF's latest forecasts, is unlikely to be significantly above 2.0 per cent.

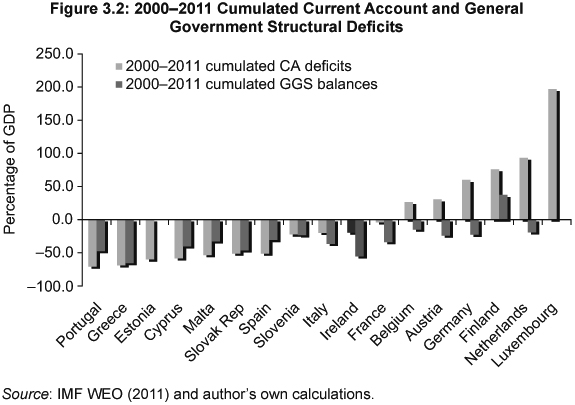

But Ireland's debt overhang, when it comes to debt types analysed by Cecchetti, Mohanty and Zampolli (2011), is beyond severe. It is outright extreme, as shown in Figure 3.1. Across the eighteen advanced economies, weighted average real economic debts stood at 307 per cent of GDP at the end of 2010 and are expected to rise to circa 310â312 per cent of GDP or gross national product (GNP) by the end of 2011. Ireland's real economy debt to GDP ratio is likely to reach close to 400 per cent of GDP and, more importantly, close to 480 per cent of GNP.

Below, we show that this level of debt overhang can be expected to permanently reduce the potential rate of growth in the Irish economy to that consistent with deflationary stagnation. In addition, we also show that the internal devaluation option is not likely to produce meaningful debt reductions at these levels of debt overhang. It is, therefore, virtually inevitable that Ireland will need to restructure some of its debts. We conclude by showing that an orderly restructuring of selective debts can result in simultaneous alleviation of the debt overhang and its effects on growth, creating potential conditions for a swift recovery from the insolvency crisis.

Is Internal Devaluation an Option?

Irish experience in the 1980sâ1990s â one of the few cases of successful deflation of public debt â is often presented as an example of what needs to be done to correct for current insolvency. This path to fiscal and economic sustainability, however, is simply invalid in the current crisis for a number of structural reasons.

Firstly, public debt overhang in the 1980s â as severe as it might have been â was not associated with simultaneous debt overhangs in the private economy. There was no structural insolvency in the banking system during the 1980s and Irish debtâGDP ratios, while higher for the public sector debt at under 120 per cent of GDP in the 1980s as opposed to the expected peak of 116 per cent of GDP in the current crisis (ex-NAMA (National Asset Management Agency) and other off-balance sheet liabilities commonly referred to as quasi-governmental debt), were much lower for the private sector. It is worth noting, however, that inclusive of NAMA's outstanding liabilities and the Central Bank of Ireland emergency assistance to the banking sector (both explicitly guaranteed by the Exchequer) Irish government and quasi-governmental debt is closer to 170 per cent of GDP. While the majority of these quasi-governmental liabilities are unlikely to generate a direct call on Exchequer finances, some, especially those relating to potential NAMA losses, can constitute a direct cost to the Irish government. Private sector debts back in the 1980s peaked at about 50 per cent of GDP and these currently stand, as variously estimated, at between 210 per cent and 289 per cent of GDP. Furthermore, while servicing costs on government debt managed to reach almost 10 per cent of GDP and 35 per cent of tax revenue back in the 1980s, servicing costs of the government debt this time around, courtesy of the troika agreements, can be expected to reach circa 4.7â6.5 per cent of GDP, depending on the underlying European Central Bank (ECB) rate assumptions, which is far less than in the past. However, the real carrying capacity of this economy is no longer measured by the actual GDP and should be benchmarked instead to GNP. In these terms, financing costs of the public debt, especially including promissory notes, can be as high as 8 per cent of GNP. The combined private and public debt burden on the economy in the 1980s was around 14 per cent. At current levels, using the lower estimate for total public and private debt, the Irish economy is spending circa 15 per cent of GDP or 18 per cent of GNP on interest payments on the non-financial debt.

Secondly, unlike in the 1980s and the 1990s, Irish policy makers no longer have control over interest rates and currency valuations. Thus, Ireland no longer can avail of surprise devaluations, similar to those that took place in 1986â1987 and subsequently.

Thirdly, unlike in the 1990s, the core twin drivers for growth, namely robust external demand and catching up with EU-average levels of capital stock and infrastructure, are no longer present today. The former cannot be expected to contribute significantly to Irish growth because our main trading partners â the US, UK and Eurozone â are currently facing long-term deleveraging of their own economies. The latter is unlikely to happen because our internal as well as global financial systems â transmitters of global savings into investment â are in the need of structural repairs that will take years. In addition, significant structural funds made available to Ireland during the 1990s by the EU are also out of our reach today.

Fourthly, Irish institutional competitiveness â especially as expressed in terms of legal, regulatory and policy frameworks international rankings, as compared to our core trading competitors â is no longer a given. Back in the 1980s and early 1990s, Ireland's relative rankings in terms of institutional quality were low. However, the gains in Irish institutional competitiveness in the early to mid-1990s were made against relatively less dynamic competition from Ireland's peers. This allowed Ireland to act as a leader in institutional innovation and precipitated significant comparative advantages to Ireland as a location for foreign direct investment (FDI), equity investments, and mergers and acquisitions. Today, Ireland is no longer ahead of the curve on institutional innovation and much of its institutional capacity is hard-wired into internationally less competitive European frameworks. This makes it more difficult for Ireland to compete for FDI and in the trade arena on the basis of superior gains in overall institutional environments.

In short, the option of deflating via growth and devaluation our debt overhang is closed. Common referencing of the 1990s Celtic Tiger boom as the benchmark to which Ireland naturally moves during the current crisis adjustments is a superficial

deus ex machina

for blindly stumbling toward a disorderly collapse of the debt-ridden economy. This is so because, as argued above, we no longer possess the same starting conditions for policy innovation and economic growth that made the Celtic Tiger of the 1990s feasible. It is also true because the global conditions of rapid growth in global FDI and lower competition pressures from the Asia Pacific region and Eastern Europe, which facilitated the development of the Celtic Tiger in the 1990s, are no longer present.

Scoping the Problem

Using the model estimates by Cecchetti, Mohanty and Zampolli (2011) and updating their results to include Ireland, the core problem faced by the Irish economy is clearly that of debt overhang. Using the study estimates, the potential reduction in Irish GDP growth over the long-term horizon arising from the combined debt overhangs can be as high as 2.1 per cent of GDP. The largest impact from debt overhang for Ireland arises from corporate debt, followed by household debt. Despite this, the Irish government's core objective to date has been to deleverage banks and to contain government debt explosion. In doing so, the government is opting for loading more debt onto households by reducing disposable after-tax incomes and refusing to implement significant savings in current public expenditure.

Ireland's debt levels are extreme. Again referencing the BIS study we see that Ireland sports the highest level of debt to GNP ratio, the second highest debt to GDP ratio and the fastest increases in 2000â2010 in both ratios in the developed world. At this junction in time, Ireland has two options: either attempt to deliver significant â close to double-digit â current account (external) surpluses to pay down the debt over time (with required surpluses of close to the interest costs required to cover debt maintenance, or some 10â12 per cent of annual GDP growth over the next ten years plus), or restructure its debts. In other words, it's either a default on growth, with all economic activity going to finance debt repayments, or a default on debt with all debt-financing resources of the economy going to finance growth.

Exports-Led Growth and Debt Overhang

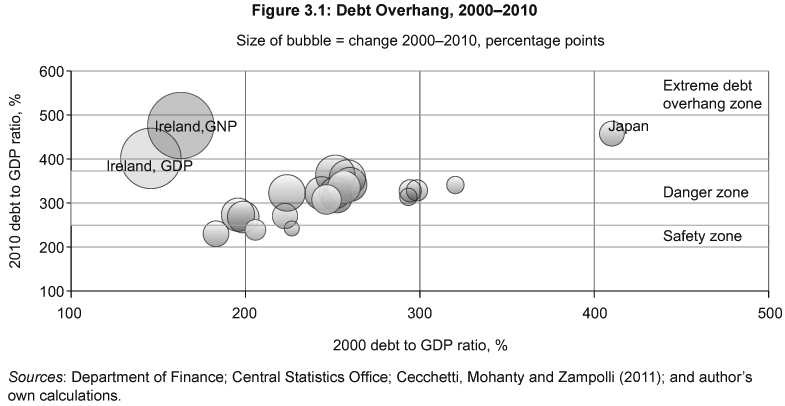

The exports-driven recovery options for Ireland are, of course, superficial. In reality, Ireland is unlikely to be able to generate significant enough surpluses on its current account to deliver growth-based debt pay downs. In the previous decade, the Irish economy ran a cumulative current account deficit amounting to 19.5 per cent of its GDP. The average current account deficit in 2000â2009 in Ireland was -2.35 per cent, and even during the boom years of the 1990s the average current account surplus achieved by the Irish economy was just 1.74 per cent of GDP â not enough to cover interest costs on combined private and public sector debts.

As the Eurozone economies pursued populist agendas of âsocial' services and subsidies expansion throughout the 1990s and 2000s, some (indeed the majority) of the European economies stagnated, implying a diminished capacity to sustain subsidies transfers within the European Union.

To see this, look no further than the links between the current account deficits (external imbalances across the entire economy, public and private) and government deficits (fiscal imbalances), as well as structural deficits (fiscal imbalances corrected for recessionary impacts).

Figure 3.2 shows cumulated current account deficits for twelve years since 2000 as well as cumulated structural deficits.