What If? (12 page)

Authors: Randall Munroe

A solar panel’s wires and circuits will eventually succumb to corrosion, but solar panels in a dry place, with well-built electronics, could easily continue providing

power for a century if they’re kept free of dust by occasional breezes or rain on the exposed panels.

If we follow a strict definition of lighting, solar-powered lights in remote locations could conceivably be the last surviving human light source.

3

But there’s another contender, and it’s a weird one.

Cherenkov radiation

Radioactivity isn’t usually visible.

Watch dials used

to be coated in radium, which made them glow. However, this glow didn’t come from the radioactivity itself. It came from the phosphorescent paint on top of the radium, which glowed when it was irradiated. Over the years, the paint has broken down. Although the watch dials are still radioactive, they no longer glow.

Watch dials, however, are not our only radioactive light source.

When radioactive particles travel through materials like water or glass, they can emit light through a sort of optical sonic boom.

Th

is light is called Cherenkov radiation, and it’s seen in the distinctive blue glow of nuclear reactor cores.

Some of our radioactive waste products, such as cesium-137, are melted

and mixed with glass, then cooled into a solid block that can be wrapped in more shielding so they can be safely transported and stored.

In the dark, these glass blocks glow blue.

Cesium-137 has a half-life of thirty years, which means that two centuries later, they’ll still be glowing with 1 percent of their original radioactivity. Since the color of the light depends only on the decay

energy, and not the amount of radiation, it will fade in brightness over time but keep the same blue color.

And thus, we arrive at our answer: Centuries from now, deep in concrete vaults, the light from our most toxic waste will still be shining.

- 1

When Enrico Fermi built the first nuclear reactor, he suspended the control rods from a rope tied to a balcony railing. In case something went wrong, next to the railing was stationed a distinguished physicist with an axe.

Th

is led to the probably apocryphal story that SCRAM stands for “Safety Control Rod Axe Man.”

- 2

Th

e purpose

of the crash was to safely incinerate the probe so it wouldn’t accidentally contaminate the nearby moons, such as the watery Europa, with Earth bacteria.

- 3

Th

e USSR built some lighthouses powered by radioactive decay, but none are still in operation.

Machine-Gun Jetpack

Q.

Is it possible to build a jetpack using downward-firing machine guns?

—Rob B

A.

I was sort of

surprised to find that the answer was yes! But to really do it right, you’ll want to talk to the Russians.

Th

e principle here is pretty simple. If you fire a bullet forward, the recoil pushes you back. So if you fire downward, the recoil should push you up.

Th

e first question we have to answer is “can a gun even lift its own weight?” If a machine gun weighs 10 pounds but produces only 8 pounds of recoil when firing, it won’t be able to lift itself off the ground, let alone lift itself plus a person.

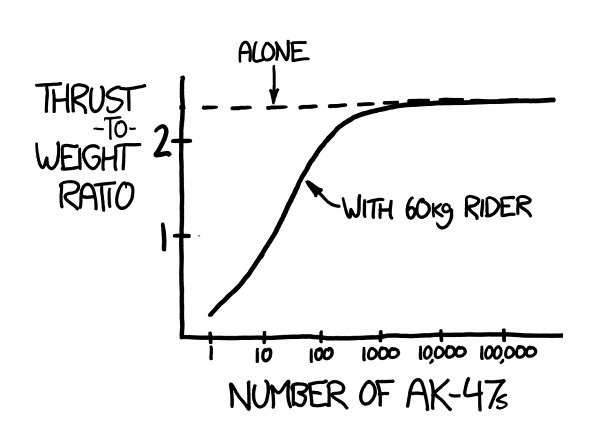

In the engineering world, the ratio between a craft’s thrust and the weight is called, appropriately,

thrust-to-weight ratio.

If it’s less than 1,

the vehicle can’t lift off.

Th

e

Saturn V

had a takeoff thrust-to-weight ratio of about 1.5.

Despite growing up in the South, I’m not really a firearms expert, so to help answer this question, I got in touch with an acquaintance in Texas.

1

Note

:

Please, PLEASE do not try this at home.

As it turns out, the

AK-47

has a thrust-to-weight ratio of around 2.

Th

is means if you stood it on

end and somehow taped down the trigger, it would rise into the air while firing.

Th

is isn’t true of all machine guns.

Th

e

M60

, for example, probably can’t produce enough recoil to lift itself off the ground.

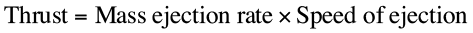

Th

e amount of thrust created by a rocket (or firing machine gun) depends on (1) how much mass it’s throwing out behind it, and (2) how fast it’s throwing it.

Th

rust is the product of these two amounts:

If an

AK-47

fires ten 8-gram bullets per second at 715 meters per second,

its thrust is:

Since the

AK-47

weighs only 10.5 pounds when loaded, it should be able to take off and accelerate upward.

In practice, the actual thrust would turn out to be up to around 30 percent higher.

Th

e

reason for this is that the gun isn’t spitting out just bullets

—

it’s also spitting out hot gas and explosive debris.

Th

e amount of extra force this adds varies by gun and cartridge.

Th

e overall efficiency also depends on whether you eject the shell casings out of the vehicle or carry them with you. I asked my Texan acquaintances if they could weigh some shell casings for my calculations. When

they had trouble finding a scale, I helpfully suggested that given the size of their arsenal, really they just need to find someone

else

who owned a scale.

2

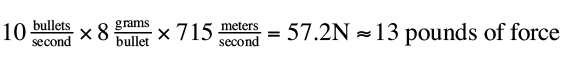

So what does all this mean for our jetpack?

Well, the

AK-47

could take off, but it doesn’t have enough spare thrust to lift anything weighing much more than a squirrel.

We can try using multiple guns. If you fire two guns at the ground, it creates twice the thrust. If each gun can lift 5 pounds more than its own weight, two can lift 10.

At this point, it’s clear where we’re headed:

You will not go to space today.

If we add enough rifles, the weight of the passenger becomes irrelevant; it’s spread over so many guns that each one barely notices. As the number of rifles increases, since the contraption is effectively many individual rifles flying in parallel, the craft’s thrust-to-weight ratio approaches that of a single, unburdened rifle:

But there’s a problem: ammunition.

An

AK-47

magazine holds 30 rounds. At 10 rounds per second, this would provide a measly three seconds of acceleration.

We can improve this with a larger magazine

—

but only up to a point. It turns out there’s no advantage to carrying more than about 250 rounds of ammunition.

Th

e reason for this is a fundamental and central problem in rocket

science: Fuel makes you heavier.

Each bullet weighs 8 grams, and the cartridge (the “whole bullet”) weighs over 16 grams. If we added more than about 250 rounds, the

AK-47

would be too heavy to take off.

Th

is suggests our optimal craft would comprise a large number of

AK-47

s (a minimum of 25 but ideally at least 300) carrying 250 rounds of ammunition each.

Th

e largest versions of this

craft could accelerate upward to vertical speeds approaching 100 meters per second, climbing over half a kilometer into the air.

So we’ve answered Rob’s question. With enough machine guns, you could fly.

But our

AK-47

rig is clearly not a practical jetpack. Can we do better?

My Texas friends suggested a series of machine guns, and I ran the numbers on each one. Some did pretty well;

the

MG-42

, a heavier machine gun, had a marginally higher thrust-to-weight ratio than the

AK-47

.

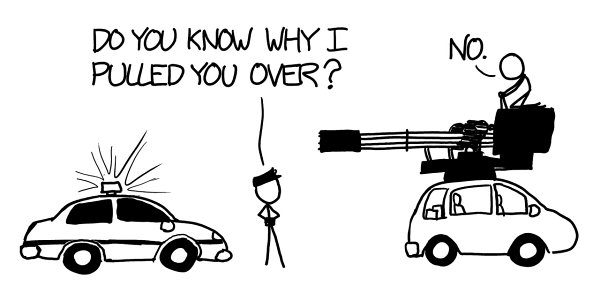

Th

en we went bigger.

Th

e

GAU-8

Avenger fires up to 60 1-pound bullets a

second

. It produces almost 5 tons of recoil force, which is crazy considering that it’s mounted in a type of plane (the

A-10

“Warthog”) whose two engines produce only 4 tons of thrust each. If you put two of them in one

aircraft, and fired both guns forward while opening up the throttle, the guns would win and you’d accelerate backward.

To put it another way: If I mounted a

GAU-8

on my car, put the car in neutral, and started firing backward from a standstill, I would be breaking the interstate speed limit in less than

three seconds

.

“Actually, what I’m confused about is how.”

As good as this gun would be as a rocket pack engine, the Russians built one that would work even better.

Th

e Gryazev-Shipunov

GS

h

-

6-30

weighs half as much as the

GAU-8

and has an even higher fire rate. Its thrust-to-weight ratio approaches 40, which means if you pointed one at the ground and fired, not only would it take off in a

rapidly expanding spray of deadly metal fragments, but you would experience 40 gees of acceleration.

Th

is is way too much. In fact, even when it was firmly mounted in an aircraft, the acceleration was a problem:

[T]he recoil . . . still had a tendency to inflict damage on the aircraft.

Th

e rate of fire was reduced to 4,000 rounds a minute but it didn’t help much. Landing lights almost

always broke after firing . . . Firing more than about 30 rounds in a burst was asking for trouble from overheating . . .

—

Greg Goebel, airvectors.net

But if you somehow braced the human rider, made the craft strong enough to survive the acceleration, wrapped the GSh-6-30 in an aerodynamic shell, and made sure it was adequately cooled . . .