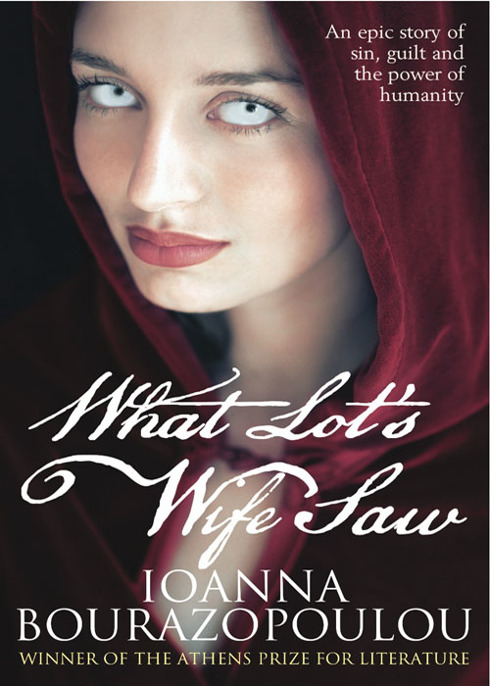

What Lot's Wife Saw

Read What Lot's Wife Saw Online

Authors: Ioanna Bourazopoulou

Main Characters

Phileas Book:

Creator of the Epistleword for

The Times

Residence: Paris

Governor Bera

Residence: the Colony

Xavier Turia Hermenegildo, aka Bernard Bateau

Residence: the Colony

Position: Presiding Judge

Place of Birth: Valencia, Spain

Selim Duden Bercant, aka Andrew Drake

Residence: the Colony

Position: Captain of the Guards

Place of Birth: Antalya, Turkey

Dusan Zehta Danilovitz, aka Montague Montenegro

Residence: the Colony

Position: Orthodox Priest

Place of Birth: Danilovgrad, Montenegro

Nicodeme Le Rhône, aka Charles Siccouane

Residence: the Colony

Position: Private Secretary to the Governor

Place of Birth: Marseilles, France

Arduino Tiberio Flagrante, aka Niccolo Fabrizio

Residence: the Colony

Position: Surgeon General

Place of Birth: Rome, Italy

Judith Swarnlake, aka Regina Bera

Residence: the Colony

Position: Governor’s Wife

Place of Birth: Liverpool, United Kingdom

Bianca Bateau

Residence: the Colony

Position: Chambermaid to Regina Bera

Place of Birth: the Colony

1

Perhaps reality is but a mass delusion

, thought Phileas Book, watching the waves of the Mediterranean Sea breaking against the concrete quays of Paris. Even after all this time, how could one reconcile the sight of the Louvre with the proximity of salt water, or of the Avenue Montparnasse with the tang of the sea breeze? The bewildered Parisians inhaled the new air, which differed from the sweet scent of the Seine, misted their car windows, clogged their nostrils and reminded them that the map of Europe had changed. They now inhabited a coastal city. They, who had once lived at the very heart of the continent, were now forced to replace their limber riverboats with huge ocean-going vessels, and the familiar path of their river with the vast Mediterranean horizon that seemed to have no end.

A quarter of a century had already passed and yet the memory of that supernatural wave, which, like a flying carpet had come unbidden one autumn from Africa and slammed into the suburbs of Montreuil and Chantilly to bring the sea to Paris’s doorstep, continued to torment the sleep of Parisians. The new port, destined to host massive ships, seemed, in their eyes, to be a horrible concrete tombstone of their romantic past. Either from bitterness or superstition, they avoided the quays in autumn, lit candles in the dry bed of the Seine and returned to their homes earlier than usual. The erstwhile City of Light reacted to the hubris of the Overflow by ageing prematurely. It had suddenly filled with wrinkles and scars, drawn curtains and unlit landings, whispers laced with guilt and shadows that walked soundlessly so as not to provoke the avenging earth. The newly built port, despite being a marvel of engineering, had so many venomous looks directed against it that it was a wonder that it had not yet detached itself from the French coast to plunge to the depths and thus bury the shame forever.

Phileas Book belonged to the somewhat infamous minority that appeared to have made peace with the insulting presence of the port. He strolled alone on the quayside this November dusk. He left his raincoat open and allowed the rolling sea, which relentlessly crashed and sucked against the concrete, to splash his shirt. He kept up a furious monologue as his boots stamped along the wet pavement. He was obviously caught up in some internal argument, typical of the ones that so often convulsed this eccentric

Times

correspondent and that lent credence to those rumours about his upcoming dismissal. Whenever Book disagreed with Book, Book sulked and ignored himself for days on end.

The Parisians who watched him strolling along the empty pier would disapprove: does this person have no memory? The truth was that Phileas Book remembered only too well. It was particularly in autumn that the demons which haunted him gained strength – they became the tortured cries, the strangled moans of the drowned, the distorted faces, the sun-parched clothes that crackled from the ingrained salt, and the arms that desperately stretched out from the muddy waves. His wanderings by the port would enrage rather than calm his demons, but Book had long accepted that cohabitation with them was mandatory and that there was enough room in his tormented consciousness for everyone, even for himself. When he felt the sea breeze caressing his face – a sea only a few blocks from Montmartre, gods are you not blushing? – the old map of France was sometimes dredged up in his brain, and he would momentarily lose awareness of his surroundings. He would walk towards the waves, believing that he was heading for one of the now inundated vineyards, but thankfully, the protective wall that the designers had presciently placed in his path would stop him from plunging over the edge. The vineyards of his memory now lay many leagues under his field of vision and had been long since colonised by seaweed, no longer able to lend any colour to the waves with the tannins of their grapes.

Phileas Book belonged to the

habitants-étrangers

of Paris, and despite never having really bonded with the locals he had bonded with the city, to the great indignation of his newspaper, which was forced to post all the material for his work from London. Paris touched him as it nobly suffered not only the pain of the horribly wounded, but also the stigma of the traitor. To those who would accuse it of conceding the use of its sea too easily to the fleet of the Seventy-Five and of its port as the seat of their Consortium, it would answer that neither the sea nor the port truly belonged to it as it had always been landlocked. It would have named the true culprits as the whims of nature that had suddenly wrapped the Mediterranean Sea around the neck of France while plunging her tender trunk – Orléans, Burgundy, Limoges – as well as the priceless fingertips – Marseilles, Nice, Toulon – to the depths, transforming her into a disembodied bust.

The dismembered do not negotiate, they lack the necessary tools for it, and so the Consortium succeeded in its submission of Paris even more completely than the Overflow had. In Book’s opinion, Paris, at least, by sentencing itself to silence, had reacted with more maturity than the others who felt the scourge of the Overflow. It did not tear its hair out in lament like the Balkans, nor curse like the Iberians, nor yet lose its sanity like the Italians had; it just aged, turned introspective and quietly mourned. This Book admired, as he himself had managed neither to mourn nor to age with dignity.

The walk in the port that he imposed on himself every evening in memory of those drowned nearly always ended violently and painfully as, walking absent-mindedly, he would bump forcefully into the steel barriers which circumscribed the public promenade. Just as he did today, banging his forehead on the fencing and acquiring a new bump. He rubbed it in surprise. Where had that steel fence come from? He was unwilling to accept that only half the quay belonged to the walkers and visitors, the contemplators, the idle, the lovers or the

habitants-étrangers

like himself; the other half belonged to those who had paid for it.

Behind the fencing stretched the vast naval base of the Consortium of the Seventy-Five, the convoluted design of which was reminiscent of an artificial fjord. A multitude of jetties invaded the sea like so many tentacles, each one splitting into branches, corners, curves, lines and breakwaters, creating a lagoon of uncountable artificial coves where the strange ships of the Consortium could be berthed. Book drew near to the fence and peered at the maze-like port, which was now blood red from the setting sun. He examined the bizarrely shaped vessels whose method of propulsion was still beyond him, and watched the workers unload wooden boxes that bore the logo of the Consortium on their sides. He heard the sacks of valuable salt being dragged along and inhaled its aroma, the aroma of fear and money. He waved nervously at the guard who had been fingering his club while watching him from behind the barrier and then abruptly turned on his heels. Book started back on his return journey, walking carefully along the edge of the promenade, knowing that if he were ever to fall into the sea, no one would pluck him out and he would have to swim all the way to Africa.

Despite the viciousness of the barrier, he preferred this side of the port for his tribute because he usually found it deserted. The Parisians would not deign to approach the borders of their ignominy and so Book enjoyed the silence and the reassuring absence of humanity. All he could see were empty benches, bare warehouse walls, bins overflowing with rubbish and limping dogs licking their wounds. Occasionally he would pass some panel with the torn remnants of advertisements on it, which could no longer reveal their message as the scraps of paper were covered by urine stains and misspelt graffiti, scrawled in thick marker pen. Only the poster of the Consortium which advertised the mysterious salt remained strangely untouched no matter where in town it appeared, as if the vandals so respected its ugliness that they refrained from defacing it further.

Even in this isolated corner of the city, the only one where Phileas Book could find some peace, the nightmarish poster dominated the fading wall. He hurried past it and felt it breathing next to him as if it were a living thing. The poster depicted the all-familiar naked woman with the violet skin, seated in the lotus position, who had no face, just a cavernous mouth from which unfolded a sinuous tongue, and from the tip of which sprouted, like the head of a mushroom, a staring eyeball. The legend underneath read “What did Lot’s wife see?” in trembling letters, as if written by a dying man.

Book closed his eyes. The tangle of symbols on this poster pursued him even in his sleep. The eye of the telescopic tongue managed to stare at him no matter where he stood in town, irrespective of whether he turned his back to it, and even, as now, when he pretended that both it and he had ceased to exist.

Under the poster a man sat cross-legged, naked from the waist up. He had placed a glass saltshaker in front of him and his red eyes gazed at it in ecstasy while he muttered monotonously, like a chant, “God is Salt.”

Book, without meaning to, tipped the shaker over with the edge of his boot.

“Blasphemer,” sighed the man and he wrapped his fingers around Book’s leg, “mindless blasphemer.”

He began to lick Book’s boot. The violet colour of his tongue left no doubts as to his condition. Book withdrew his foot carefully and pushed him gently with his heel, to dislodge him without hurting him. The man put up no resistance; they rarely did. They were multiplying dangerously, Book thought, and one always found them under the posters. He returned to his office determined to wash his boots with soap.

Book’s office was barely large enough for himself: a table, an armchair and an umbrella stand. Actually, it was just an attic over a ground-floor camping goods store, which Book rented along with the use of a toilet. It was never intended to be a place to receive visitors so it lacked superfluous furniture such as a second chair.