What She Saw (9 page)

Authors: Mark Roberts

The girl made the sign of the cross and fell into a prayerful mode.

It was Macy Conner, eyes shut, face composed peacefully.

Rosen left the Portakabin and, walking quietly, stood behind Macy. The carnations looked just about fit for the bin, and the price drop label read â60p'. A poor little girl's offering for another unfortunate child.

She opened her eyes, turned and said, âMr Rosen?'

âHello, Macy.'

âHow's Thomas?' she asked. âHe's not very well.'

âIs he still alive?'

âYes.'

âI'm leaving flowers because I want him to know I'm thinking about him.'

âThat's very thoughtful of you.'

âCan you tell him I'm praying for him?'

âNext time I see him, I will,' said Rosen.

The cut on her lip was vivid and looked set to tear and pour blood.

Even after your own trauma

, thought Rosen,

you're mindful of the suffering of others

.

âDo you know his mum and dad?'

âYes.'

âIt must be terrible for them.'

Rosen glanced at the small card sellotaped to the plastic bag holding the virtually dead carnations.

To Thomas

Get well soon

Macy

The handwriting was immaculate linked print, and displayed a maturity beyond her years. The message was, Rosen guessed, the well-intentioned but naïve sentiment of a ten year old.

âMr Rosen?'

He smiled, encouraging her, hopeful she'd come up with some other detail but not wishing to push her too hard.

âI've got something to tell you.'

âGo on.'

âWe weren't totally honest with you when we called in over there.' She indicated the Portakabin with a nod of her head and a look of shame.

âOK?'

âMum did have a bad head last night and that's partly why she couldn't go to the shop for the electricity card. But there was another reason why I had to go and Mum couldn't.' She touched the swelling on her lip. âMy grandma lives with us. She's that sick she's mostly in bed. Mum doesn't let her be on her own in the flat. In case she dies of the cancer. I've heard Mum talk to the nurses. She can't talk to me. I've tried to talk about things but she just clams up. She told the nurses she was terrified of her mother dying. And scared of her dying all on her own. When we came to see you this morning, my big brother, Paul, he was in the flat with Grandma, but Paul wasn't around for some of last night and so Mum let me go to the shop for the electricity card.'

âI'm very sad to hear about your grandma.'

Macy looked at Rosen directly, openly. âSo am I. I'm so close to her. Mr Rosen, I was on my way over to your cabin to tell you because I've been worried sick all afternoon.'

âWhat's been worrying you, Macy?'

He felt the warm stirring of a bond forming with the little girl before him.

âBecause we didn't tell you the whole truth. About why it was me who had to go to the shop. I couldn't say anything when I was with

Mum. I'm sorry. It's wrong to lie and it's really bad to lie to the police.'

âYou've nothing to be sorry to me for. I understand. You've been a wonderful help, a great witness and a brave girl. Don't think of it as lying, think of it as being tactful.'

âTactful?'

âMindful of the feelings of others, your mum's feelings.'

âYou're not angry with me?'

âI'm pleased with you.'

Relief swept through her features and a moment of tenderness overwhelmed Rosen.

â“It's important to tell the truth at all times.” That's what my grandma taught me. Truth.'

Rosen, who agreed in principle but not always in practice, smiled.

âYour grandma sounds like a very good woman.'

âShe's the best. Because she's dying, I think that's why I feel so sorry for Thomas's mum and dad. Do you think he's going to die?'

âI'm not a doctor, Macy, I can't say, but I understand what you mean. Your situation has taught you to empathize with Mr and Mrs Glass, and that's a really good thing to do, it's very grown up.'

She held out a hand and Rosen shook with her. Her fingers were cold and he sat on his fatherly instinct and the words

Put your gloves on

because there was the possibility that she didn't own a pair.

âI've got to go to Lewisham Library, to pick up some books. Grandma likes me to read to her. I've got special permission from Mrs Dodson, who's head of the library, to get Gran's books from the grown-ups' section.'

He hadn't noticed the bag on her back.

âMacy?'

She looked at him, alert and eager to please.

âRemember when we were talking this morning, in the cabin? Did you remember that thing that you said you'd blocked out?'

âIt's trapped.' She touched her head. âIn here. It's been bugging me

all day. Soon as I remember, Mr Rosen, I'll come and see you, straight away, I promise.'

Rosen watched Macy walk away under the weight of a bag of books, strapped from right shoulder to left hip. He looked at her pitiful offering of carnations and the scorched tarmac where Thomas had been set alight.

He walked back across Bannerman Square to the graffiti-daubed wall, bracing himself to recreate the horror of Thomas Glass's experience in the back of a burning car.

21

4.03 P.M.

R

osen worked backwards from the point where Stevie had lain Thomas down.

He dipped under the scene-of-crime tape and crouched at the pothole where Thomas had fallen into a puddle. He looked up at the spray-painted aerosol eye.

The painted eye stared directly back at Rosen. As he moved his head a little to the left, the eye held his gaze.

He stood up and walked into the charred rectangle where the car had burned, aligned the front and back of the vehicle, and positioned himself in the space next to the back left-hand door. He pictured the rising flames and imagined the complete claustrophobia Thomas must have felt, banging on the window maybe, staring out, desperation mounting.

Rosen dipped to the height of a child in the back of that car. Through the imaginary flames and rising smoke, he stared directly at the painted eye and the words,

The position of this car, this was no accident

sounded clearly inside his head.

Bang, bang, bang

, a fist on the window. A door they'd failed to lock. A door that fell open under a watchful, sinister eye.

He rose to his full height and made his way slowly to the pothole where Thomas had fallen; imagined the mind-bending terror, his

agony; pictured Stevie running towards that place through the sodium-tinted night.

And his focus came back to the eye on the wall, the complementary black and white, the black of the oval outline, the white inner eye that housed all the details, the sinister pupil with the life-like speck of white light and the spokes linking the circumference of the eye to the centre.

âDCI Rosen?'

Snapped from the moment by the sound of a man's voice, Rosen glanced over his shoulder. A well-dressed man in his thirties, tall, close to six foot four, who wouldn't have looked out of place in a line-up of rising political stars, was approaching.

He stayed on the other side of the scene-of-crime tape and said, âDCI Rosen? I'm James Henshaw. Chief Superintendent Baxter told me you'd be here.'

Rosen recognized his face and remembered seeing Henshaw on a TV documentary about Fred and Rosemary West, giving his expert opinion on their psychology, their shared mission, their hand-in-glove marital murder unit. He had been a convincing and articulate pundit.

âI came as soon as I picked this up,' Henshaw said, handing Rosen his card, and a folded sheet of paper. Rosen opened it and saw it was an email from Baxter confirming that Rosen wanted Henshaw on the team.

Rosen lifted the scene-of-crime tape and Henshaw ducked under it. As he shook hands with Rosen, the profiler smiled but Rosen read a sadness in him that sparked something buried deeply in his memory. When he let go of Henshaw's hand, although unsure of the details, Rosen knew he was in the presence of a man who had suffered deep and personal tragedy.

âThank you for coming so quickly, James. Your timing's impeccable. I think I've come to a time, place and concept that you could really help me with,' said Rosen. He pointed at the graffiti.

âThis is the exact place where Thomas was set on fire?' asked Henshaw,

putting on a pair of glasses to study the image. He stood quiet and still while Rosen waited, watching the intensity of his reaction. âHe or she's a very good artist,' said Henshaw, eventually. âIt's been painted under pressure, possibly in the dead of night with a spray can in one hand and a torch in the other.'

Taking a digital camera from his pocket, Henshaw asked, âMay I?'

At Rosen's nod, Henshaw took several photographs of the eye. Then the profiler stepped in closer and examined the eye narrowly, nearly scraping his nose on the bricks in the wall.

âWhat's your take on this graffiti?' asked Rosen.

âThe cave paintings of our time.'

Rosen looked at the graffiti with fresh eyes, breaking it down into its component parts as Henshaw pressed ârecord' on his phone and dictated: âBlack oval outline, white, dappled grey within the white, fifteen spokes outside to centre, perspective perfect, execution exquisite, mindset abnormal.'

Henshaw turned, pressed âstop' and pocketed his phone. For some reason, he reminded Rosen of a pilgrim standing before a holy icon. Henshaw looked at Rosen.

â“Mindset abnormal”?' asked Rosen.

âMy instinct and my understanding are telling me that the combined content and quality' â Henshaw looked at the eye again, as if double-checking his judgement before delivering it â âmeans this is the work of a damaged mind.'

âThe thing is,' said Rosen. âWe had a trashed CCTV camera on that wall. . .' He pointed.

âWhere's it now?'

âScientific Support took it away.'

Henshaw's attention drifted back to the graffiti. âHollow scrawl or Holy Scripture?' He did a visual three-point turn: wall, scorched earth, eye.

âIt's no accident he was brought here,' said Rosen. He moved in closer.

The wall had been covered on both sides with fingerprint dust, but so far nothing concrete had been uncovered from the dozen different, partial palm- and fingerprints picked up on the bricks.

He leaned over the wall and, dead tired, wondered if his eyes were playing tricks on him.

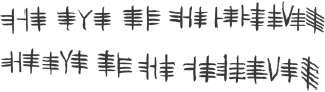

There were two horizontal lines of symbols scratched lightly with a sharp point on the surface of the bricks directly behind the eye on the other side of the wall.

He walked around the wall to get a full head-on view. For a moment, it appeared like an optical illusion created by the wear and tear of time on the brickwork but then, superficial as the marks were, the symbols were as real and vivid as the eye on the other side.

How come no one picked up on this

? thought Rosen.

Me included?

He felt the presence of Henshaw behind him.

Rosen squatted on his heels and stared at the symbols. From his pocket, he produced a torch and threw yellow light onto the marks on the brickwork. He looked at the top line and made out five sets with four spaces. Down to the second line. Again. Five sets. Four spaces.

He looked at the first set, top line, and compared it to the first set, bottom line. The symbols correlated. The second set, top line, matched the symbols below. Third top and bottom, the same. Fourth top and bottom, matched. Finally, he looked at the fifth set.

He stood up and took out his notebook and pen. At a fevered rate, Rosen drew lines on a blank page.

âWhat's this?' Henshaw crouched down.

Rosen counted the dashes.

âLet's call these marks words,' said Rosen. âThe first four words top and bottom are identical. The last word, top and bottom, has the same number of letters and final two letters the same.'