What to expect when you're expecting (146 page)

Read What to expect when you're expecting Online

Authors: Heidi Murkoff,Sharon Mazel

Tags: #Health & Fitness, #Postnatal care, #General, #Family & Relationships, #Pregnancy & Childbirth, #Pregnancy, #Childbirth, #Prenatal care

“Will I have to be hooked up to a fetal monitor the whole time I’m in labor? What’s the point of it anyway?”

For someone who’s spent the first nine months of his or her life floating peacefully in a warm and comforting amniotic bath, the trip through the narrow confines of the maternal pelvis will be no joyride. Your baby will be squeezed, compressed, pushed, and molded with every contraction. And though most babies sail through the birth canal without a problem, others find the stress of being squeezed, compressed, pushed, and molded too difficult, and they respond with decelerations in heart rate, rapid or slowed-down movement, or other signs of fetal distress. A fetal monitor assesses how your baby is handling the stresses of labor by gauging the response of its heartbeat to the contractions of the uterus.

But does that assessment need to be continuous? Most experts say no, citing research showing that for low-risk women with unmedicated deliveries, intermittent fetal heart checks using a Doppler or fetal monitor are an effective way to assess a baby’s condition. So if you fit in that category, you probably won’t have to be attached to a fetal monitor for the entire duration of your labor. If, however, you’re being induced, have an epidural, or have certain risk factors (such as meconium staining), you’re most likely going to be hooked up to an electronic fetal monitor throughout your labor.

There are three types of continuous fetal monitoring:

External monitoring.

In this type of monitoring, used most frequently, two devices are strapped to the abdomen. One, an ultrasound transducer, picks up the fetal heartbeat. The other, a pressure-sensitive gauge, measures the intensity and duration of uterine contractions. Both are connected to a monitor, and the measurements are recorded on a digital and paper readout. When you’re connected to an external monitor, you’ll be able to move around in your bed or on a chair nearby, but you won’t have complete freedom of movement, unless telemetry monitoring is being used (see this page).

During the second (pushing) stage of labor, when contractions may come so fast and furious that it’s hard to know when to push and when to hold back, the monitor can be used to accurately signal the beginning and end of each contraction. Or the use of the monitor may be all but abandoned during this stage, so as not to interfere with your concentration. In this case, your baby’s heart rate will be checked periodically with a Doppler.

Internal monitoring.

When more accurate results are required—such as when there is reason to suspect fetal distress—an internal monitor may be used. In this type of monitoring, a tiny electrode is inserted through your vagina onto your baby’s scalp, and a catheter is placed in your uterus or an external pressure gauge is strapped to your abdomen to measure the strength of your contractions. Though internal monitoring gives a slightly more accurate record of the baby’s heart rate and your contractions than an external monitor, it’s only used when necessary (since its use comes with a slight risk of infection). Your baby may have a small bruise or scratch where the electrode was attached, but it’ll heal in a few days. You’ll be more limited in your movement with an internal monitor, but you’ll still be able to move from side to side.

Telemetry monitoring.

Available only in some hospitals, this type of monitoring uses a transmitter on your thigh to transmit the baby’s heart tones (via radio waves) to the nurse’s station—allowing you to take a lap or two around the hallway while still having constant monitoring.

Be aware that with both internal and external types of monitoring, false alarms are common. The machine can start beeping loudly if the transducer has slipped out of place, if the baby has shifted positions, if the monitor isn’t working right, or if contractions have suddenly picked up in intensity. Your practitioner will take all these factors and others into account before concluding that your baby really is in trouble. If the abnormal readings do continue, several other assessments can be performed (such as fetal scalp stimulation) to determine the cause of the distress. If fetal distress is confirmed, then cesarean delivery is usually called for.

“I’m afraid that if my water doesn’t break on its own, the doctor will have to rupture the membranes artificially. Won’t that hurt?”

Most women actually don’t feel a thing when their membranes are artificially ruptured, particularly if they’re already in labor (there are far more significant pains to cope with then). If you do experience a little discomfort, it’ll more likely be from the introduction into the vagina of the Amniohook (the long plastic device that looks like a sharp-pointed crochet hook and is used to perform the procedure) than from the rupture itself. Chances are, all you’ll really notice is a gush of water, followed soon—at least that’s the hope—by harder and faster contractions that will get your baby moving. Artificial rupture of the membranes is also performed to allow for other procedures, such as internal fetal monitoring, when necessary.

Though the latest research seems to indicate that artificially rupturing the membranes doesn’t shorten the length of labor or decrease the need for Pitocin, many practitioners still turn to artificial rupture in an attempt to help move a sluggish labor along. If there’s no compelling reason to rupture them (labor’s moving along just fine), you and your practitioner may decide to hold off and let them rupture naturally. Occasionally, membranes stay stubbornly intact throughout delivery (the baby arrives with the bag of waters still surrounding him or her, which means it will need to be ruptured right after birth), and that’s fine, too.

“I heard episiotomies aren’t routine anymore. Is that true?”

Happily, you’ve heard right. An episiotomy—a surgical cut in your perineum (the muscular area between your vagina and your anus) to enlarge the vaginal opening just before the baby’s head emerges—is no longer performed routinely at delivery. These days, in fact, midwives and most doctors rarely make the cut without a good reason.

It wasn’t always that way. The episiotomy was once thought to prevent spontaneous tearing of the perineum and postpartum urinary and fecal incontinence, as well as reduce the risk in the newborn of birth trauma (from the baby’s head pushing long and hard against the perineum). But it’s now known that infants fare just fine without an episiotomy, and mothers, too, seem to do better without it. An average total labor doesn’t seem to be any longer, and mothers often experience less blood loss, less infection, and less perineal pain after delivery without an episiotomy (though you can still have blood loss and infection with a tear). What’s more, research has shown that episiotomies are more likely than spontaneous tears to turn into serious third- or fourth-degree tears (those that go close to or through the rectum, sometimes causing fecal incontinence).

But while routine episiotomies are no longer recommended, there is still a place for them in certain birth scenarios. Episiotomies may be indicated when a baby is large and needs a roomier exit route, when the baby needs to be delivered rapidly, when forceps or vacuum delivery need to be performed, or for the relief of shoulder dystocia (a shoulder gets stuck in the birth canal during delivery).

If you do need an episiotomy, you’ll get an injection (if there’s time) of local pain relief before the cut, though you may not need a local if you’re already anesthetized from an epidural or if your perineum is thinned out and already numb from the pressure of your baby’s head during crowning. Your practitioner will then take surgical scissors and make either a median (also called midline) incision (a cut made directly toward the rectum) or a mediolateral incision (which slants away from the rectum). After delivery of your baby and the placenta, the practitioner will stitch up the cut (you’ll get a shot of local pain medication if you didn’t receive one before or if your epidural has worn off).

To reduce the possibility that you’ll need an episiotomy and to ease delivery without one, some midwives recommend perineal massage (see

page 352

) for a few weeks before your due date if you’re a first-time mom. (If you’ve delivered vaginally before, you’re already stretched, so do-ahead massage probably won’t accomplish much.) During labor, the following can also help: warm compresses to lessen perineal discomfort, perineal massage, standing or squatting and exhaling or grunting while pushing to facilitate stretching of the perineum. During the pushing phase, your practitioner will probably use perineal support—applying gentle counterpressure to the perineum so your baby’s head doesn’t push out too quickly and cause an unnecessary tear.

If you haven’t already, discuss the episiotomy issue with your practitioner. It’s very likely he or she will agree that the procedure should not be performed unless there’s a good reason. Document your feelings about episiotomies in your birth plan, too, if you like. But keep in mind that, very occasionally, episiotomies do turn out to be necessary, and the final decision should be made in the delivery or birthing room—when that cute little head is crowning.

“How likely will it be that I’ll need forceps during delivery?”

Pretty unlikely these days. Forceps—long curved tong-like devices designed to help a baby make his or her descent down the birth canal—are used in only a very small percentage of deliveries (vacuum extraction is more common; see next question). But if your practitioner does decide to use forceps, rest assured; they are as safe as a C-section or vacuum extraction when used correctly by an experienced practitioner (many younger doctors have not been trained in their use, and some are reluctant to use them).

Forceps are considered when a laboring mom is just plain exhausted or if she has a heart condition or very high blood pressure that might make strenuous pushing harmful to her health. They might also be used if the baby needs to be delivered in a hurry because of fetal distress (assuming the baby is in a favorable position—for example, close to crowning) or if the baby’s in an unfavorable position during the pushing stage (the forceps can be used to rotate the baby’s head to facilitate the birth).

Your cervix will have to be fully dilated, your bladder empty, and your membranes ruptured before forceps are used. Then you’ll be numbed with a local anesthetic (unless you already have an epidural in place). You’ll also likely receive an episiotomy to enlarge the vaginal opening to allow for placement of the forceps. The curved tongs of the forceps will then be cradled one at a time around the temples of the baby’s crowning head, locked into position, and used to gently deliver the baby. There may be some bruising or swelling on the baby’s scalp from the forceps, but it will usually go away within a few days after birth.

If your practitioner attempts delivery with forceps, but the attempt is unsuccessful, you’ll likely undergo a C-section.

“My friend’s ob used a vacuum extractor to help deliver her baby. Is that the same as forceps?”

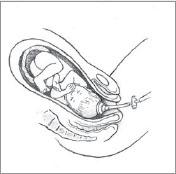

It does the same job. The vacuum extractor is a plastic cup placed on the baby’s head, and it uses gentle suction to help guide him or her out of the birth canal. The suction prevents the baby’s head from moving back up the birth canal between contractions and can be used to help mom out while she is pushing during contractions. Vacuum extraction is used in about 5 percent of deliveries and offers a good alternative to both forceps and C-section under the right circumstances.

Your practitioner would use vacuum extraction for the same reason forceps would be used during delivery (see previous question). Vacuum deliveries are associated with less trauma to the vagina (and possibly a lower chance of needing an episiotomy) and less need for local anesthesia than forceps, which is another reason why more practitioners opt for them over forceps these days.

Babies born with vacuum extraction experience some swelling on the scalp, but it usually isn’t serious, doesn’t require treatment, and goes away within a few days. As with forceps, if the vacuum extractor isn’t working successfully to help deliver the baby, a cesarean delivery is recommended.

Vacuum Extractor

If during delivery your doctor suggests the need for vacuum extraction to speed things up, you might want to ask if you can rest for several contractions (time permitting) before trying again; such a break might give you the second wind you need to push your baby out effectively. You can also try changing your position: Get up on all fours, or squat; the force of gravity might shift the baby’s head.

Before you go into labor, ask your practitioner any questions you have about the possible use of vacuum extraction (or forceps). The more you know, the better prepared you’ll be for anything that comes your way during childbirth.

“I know you’re not supposed to lie flat on your back during labor. But what position is best?”