When a Crocodile Eats the Sun

Copyright © 2006 by Peter Godwin

All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Little, Brown and Company

Hachette Book Group USA

237 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10169

Visit our Web site at

www.HachetteBookGroupUSA.com

First eBook Edition: April 2008

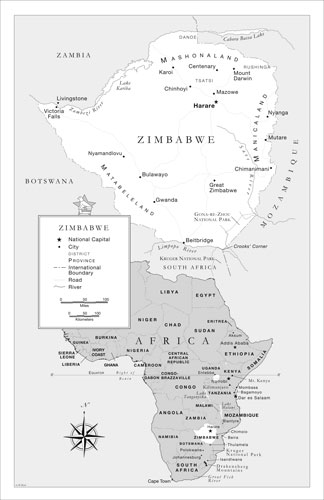

Map by George W. Ward

ISBN: 978-0-316-03209-4

Contents

Also by Peter Godwin

Mukiwa:

A White Boy in Africa

Wild at Heart:

Man and Beast in Southern Africa

(

PHOTOGRAPHS BY

C

HRIS

J

OHNS, FOREWORD BY

N

ELSON

M

ANDELA

)

The Three of Us: A New Life in New York

(

WRITTEN WITH

J

OANNA

C

OLES

)

“Rhodesians Never Die”:

The Impact of War and Political Change on White Rhodesia, c. 1970–1980

(

WRITTEN WITH

I

AN

H

ANCOCK

)

IN MEMORY OF

G

EORGE

G

ODWIN

For the next generation

Hugo, Thomas, Holly, and Xanthe

M

Y FATHER IS NOW

more than an hour late. We sit on a mossy stone bench under a giant fig tree, waiting for him. We have finished the little Chinese thermos of coffee that my mother prepared, and the sandwiches.

Tapera looks up. The motion pleats the base of his shaven skull into an accordion of glistening brown flesh.

“At last,” he says. “He is arrived.”

The car, long and low and sinister, glides slowly toward us, only the black roof visible above the reef of elephant grass. It passes us and then backs up into position.

Keith jumps out of the passenger side.

“Sorry we’re late,” he says. “We were stopped at a police roadblock up on Rotten Row. They wanted to check inside. Can you believe it?”

He hands me a clipboard. “Sign here and here.”

The driver reaches down to unlatch the tailgate. It opens with a gentle hydraulic sigh. Inside is a steel coffin. Together we slide it out and carry it over to the concrete steps. Keith unlatches the lid to reveal a body tightly bound in a white linen winding-sheet.

“Why don’t you take the top,” he says.

I ease one hand under the back of my father’s head and my other arm under his shoulders, and I give him a last little hug. He is cool and surprisingly soft to my touch. The others arrange themselves along his body, and on Keith’s count we lift it out of the coffin.

We shuffle up the concrete stairs that lead to the top of the iron crib. We have woven fresh green branches through its black bars. And on top of the tiers of logs inside it, we have placed a thick bed of pine needles and garnished it with fragrant pine shavings. Upon this bed we lay my father down.

Gently, Tapera lifts Dad’s head to place a small eucalyptus log under his neck as a pillow. As he does so the shroud peeks open at a fold, and I get a sudden, shocking glimpse of my father’s face. His jaw, grizzled with salt-and-pepper stubble; the little dents on his nose where his glasses rested; his mustache, slightly shaggy and unkempt now; the lines of his brow relaxed at last in death. And then, as his head settles back, the shroud stretches shut again, and he is gone.

Tapera is staggering up the steps with a heavy musasa log. He places it on top of the body.

“Huuuh.” My father exhales one last loud breath with the weight of it.

“It is necessary,” Tapera says quietly, “to hold the body down in case . . .” He pauses to think if there is a way to say this delicately. “In case it explodes because of the buildup of the gases.” He looks unhappily at the ground. “It happens sometimes, you know.”

Keith slides the empty coffin back into the hearse and drives away down the lane, where it is soon swallowed up again by the green gullet of grass.

The old black grave digger, Robert, has his hand in front of me now. His palm is yellow and barnacled with calluses. He is offering me a small Bic lighter made of fluorescent blue plastic.

“It is traditional for the son to light the fire,” says Tapera, and he nods me forward.

I stroke my father’s brow gently through the shroud, kiss his forehead. Then I flick the lighter. It fires up on my third trembling attempt, and I walk slowly around the base of the trolley, lighting the kindling. It crackles and pops as the flames take hold and shiver up the tower of logs to lick at the linen shroud. Quickly, before the cloth burns away to reveal the scorched flesh beneath, Tapera hands me a long metal T-bar and instructs me to place it against the back of the trolley, while he does the same next to me. We both heave at it. For a moment the trolley remains stuck on its rusty rails. Then it groans into motion and squeaks slowly toward the jaws of the old redbrick kiln a few yards away.

“Sorry it’s so difficult,” says Tapera, breathing heavily with the effort. “The wheel bearings are shot.”

The flaming pyre enters the kiln and lurches to rest against the buffers. Robert, the grave digger, clangs shut the cast-iron doors and pulls down the heavy latch to lock them.

We all squint up into the brilliant blue sky to see if the fire is drawing. A plume of milky smoke flows up from the chimney stack, up through the green and red canopy of the overhanging flame tree.

“She is a good fire,” says Tapera. “She burns well.”

July 1996

I

AM ON ASSIGNMENT

in Zululand for

National Geographic

magazine when I get the news that my father is gravely ill.

It is night, and I am sitting around a fire with Prince Galenja Biyela. I am sitting lower than he is to show due respect. Biyela is ninety-something — he doesn’t know exactly — tall and thin and straight backed, with hair and beard quite white. Around his shoulders, he has draped a leopard skin in such a way that the tail lies straight down his chest, like a furry necktie. A yard of mahogany shin gleams between his tattered sneakers and the cuffs of his trousers. His long fingers are closed around the gnarled head of a knobkerrie, a cudgel.

“All is well,” he declares.

It is his only English phrase. He speaks in classical Zulu, his words almost Italianate, lubricated by vowels at either end.

His tribal acolytes start chanting his praise names.

“You are the bull that paws the earth,” they call.

“Your highness,” they sing, “we will bow down to the one who growls.”

Prince Biyela’s grandfather, Nkosani — the small king — of the Black Mamba regiment, was the hero of Isandlwana, the battle in which the Zulus famously trounced the mighty British Empire in 1879. Tonight, the old prince wishes to revel in the glory days, to relive the humbling of the white man.

He tells me how the British watched in awe as twenty-five thousand Zulu warriors stepped over the skyline and began to advance, chanting all the while, and stopping every so often to stomp the ground in unison, sending a tremor through the earth that could be felt for miles. He tells me how the

impi,

the Zulu regiments, were armed with short stabbing spears,

ixlwa,

a word you pronounce by pulling your tongue off the roof of your mouth, a word that deliberately imitates the sucking sound made by a blade when it’s pulled out of human flesh.

As the warriors advanced, he says, their places on the ridge above were taken by thousands of Zulu women, urging on their army in the traditional way by ululating, an eerie high-pitched keening that filled the air.

Biyela tells me how the Black Mamba regiment was cut down by withering gunfire until, he says, after nearly two hours, the force “was as small as a sparrow’s kidney,” and the remaining men were on their bellies, taking cover. And how his grandfather, Nkosani, seeing what was happening, strode up to the front line, dressed in all his princely paraphernalia — his ostrich plume headdress and his lion claw necklaces — and berated them. Electrified by his example, the young warriors leaped up and again surged forward, overwhelming the men of the British line, even as Nkosani was felled by a British sniper with a single shot to the head.

And in the final stages of the battle, when the handful of surviving British soldiers had run out of bullets, a most unusual event occurred. The moon passed in front of the sun, and the earth grew dark, like night. And the Zulu

impi

stopped their killing while this eclipse took place. But when the light returned, they resumed the bloodletting.

Biyela tells me that night how his grandfather’s warriors, having overrun the main British camp, dashed from tent to tent mopping up the stragglers — the cooks and the messengers and the drummer boys — until they crashed into one tent to find a newspaper correspondent sitting at his campaign table, penning his report.

“Just like you are now,” he says to me, and his acolytes all laugh until Biyela raises his hand for silence.

“They said to him, ‘

Hau!

What are you doing in here, sitting at a table? Why aren’t you out there fighting?’ And this man, he was a local white who could speak some Zulu, he said, ‘I am writing a report on the battle, for my people.’

“?‘Oh,’ they said, ‘all right.’ And they left him.

“But soon afterward, when they heard that my grandfather Nkosani had been shot, they ran back to the tent and said to the journalist there, ‘Now that our

induna

[leader] has been killed, there is no point in making a report anymore,’ and with that they killed him.”

Biyela’s men nod. I keep writing.

At the end, according to the few British soldiers who escaped, the Zulus went mad with bloodlust, killing even the horses and the mules and the oxen. They disemboweled each dead British soldier so that his spirit could escape his body and not haunt his killer. And if an enemy soldier had been seen to be particularly brave, the

impi

cut out his gallbladder and sucked on it, to absorb the dead man’s courage, and bellowed,

“Igatla!”

— “I have eaten!”

And that night Biyela tells me how, once the battlefield fell quiet, a great wail was heard from the retinue of the Zulu women, as they mourned their dead. And this wail moved like a ripple through village after village until finally it reached the Zulu capital, Ulundi, fifty miles distant.

And here, Prince Biyela ends his telling, choosing not to dwell on what followed the Zulu victory. For the eclipse of the sun was a bad portent, and it drew down terrible times — the British re-inforced and quickly snuffed out the independent Zulu nation. But still their spirit was not entirely doused. Their ferocity was merely curbed, and there was a sullen dignity to their defeat. It is said that before they would sign the surrender proclamation, one old

induna

stood and said to Sir Garnet Wolseley, “Today we will admit that we are your dogs, but you must first write it there, that the other tribes are the fleas on our backs.”

Prince Biyela pauses to gulp another shot of the Queen’s tears, as the Zulus call Natal gin, and the silence is jarred by a ring tone.

“

uMakhalekhukhwini,

” says one of his acolytes — it means “the screaming in the pocket,” Zulu for

cell phone

— and they all grope around in the dark in their jackets and bags. It turns out to be mine. I reach in to cut it off, but it’s my parents’ number in Zimbabwe, eight hundred miles to the north. They never call just to chat. I excuse myself.

My mother’s voice sounds strained. “It’s your father,” she says. “He’s had a heart attack. I think you’d better come home.”