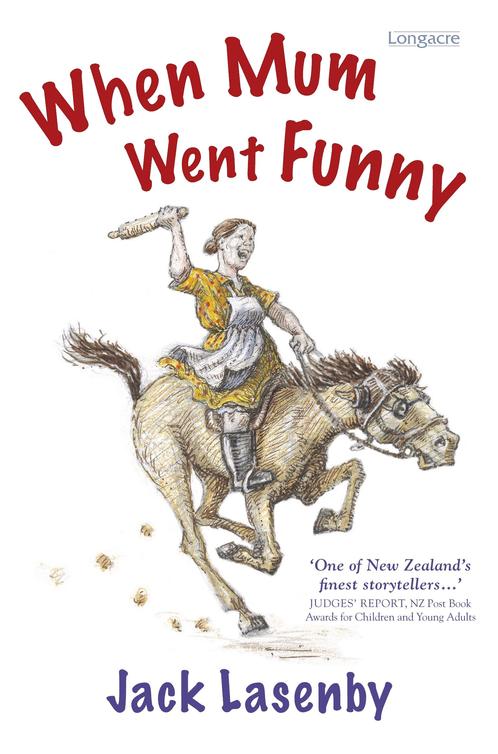

When Mum Went Funny

Read When Mum Went Funny Online

Authors: Jack Lasenby

M

um has all kinds of strange ideas: she’ll feed you food pills, so she doesn’t have to cook. There’s always nail soup when the cupboard is bare. If you’re not careful, she’ll make you go to school from six in the morning to five at night (if she doesn’t come with you!). And a special warning, keep an extra close eye on Mum when the circus rolls into town. She might try to get in the lion’s cage, or even sell you to the circus.

Flying to school in a Lancaster Bomber, you’ve got to keep your eyes peeled for Messerschmitt attacks. But that’s not the half of it! It was a battle of wits, when Mum got that look in her eye.

With his masterful storytelling, Jack Lasenby makes magic out of the everyday

…

My first night in the bush, over fifty years ago, I cut a tea-tree stick to hang my billy over the fire. The heat curled up one end, like a handle, and I used it as a walking stick. It helped me swim rivers, climb mountains, and fight off wolves, kehuas, and polar bears in the Vast Untrodden Ureweras; it came in handy as a tent pole; it saw and heard so many things, it became very wise.

Once, about midnight, I woke and heard my Wise Old Tea-Tree Walking Stick telling a story to the billy. I wrote it down, signed it with my name, and published it in the

Woman’s Weekly.

My first story!

Most people don’t know that – at midnight – walking sticks can walk around by themselves. A couple of nights ago, I woke and heard voices. I sneaked out and saw my Wise Old Tea-Tree Walking Stick sitting in my chair, telling a story to my computer who wrote it down, signed it with my name, and emailed it to my publishers. The cheek of them!

I stood my Wise Old Tea-Tree Walking Stick on his head and told him, “I’ve a good mind to split you up for kindling wood!” And I told my computer, “Come the mong on me just once more, and I’ll pull out your plug!”

Tonight, I’ll to go to bed and pretend to snore. At midnight, still snoring loudly, I’ll tiptoe out and see if they’re up to their tricks again.

Now that I’m old, and my hair and teeth and ears are grey, I thought I should tell you the true truth about where I pinch my ideas from.

Yours Truly Truthfully,

Jack Lasenby

This book is dedicated to my Wise Old Tea-Tree Walking Stick.

I wish to acknowledge that I pinch all my ideas from my Wise Old Tea-Tree Walking Stick.

II

Squabbling Over the Rear Turret

VI

Putting the Car Up On Blocks

VIII

From Six in the Morning to Five at Night

XI

Riding in Circles, and the Immelmann Turn

XVII

To Last Him Through the Winter

XXI

Some People Don’t Know When They’re Well Off

XXII

The Day of the School Picnic

XXIII

When Mum Wanted to Go to School

XXIV

The Day that Mum Wore Her Hat to the Station

I

f it hadn’t been for Kate, I don’t know what would have become of us, when Mum started going funny. Kate’s our older sister. Then there’s me. Then Betty, and Jimmy; they were just little kids when all this happened.

Betty got along all right, she knew how to look after herself. I suppose I was okay, too. But Jimmy was different.

Jimmy always had a dirty bandage on his foot or a finger. If one of us got a stone bruise from running on the road in bare feet, or a prickle that had to be dug out, it was always Jimmy. He fell, he tripped, he tumbled; he knocked himself about. When I look back, I wonder how he lasted.

Behind the wash-house door, Mum kept a bagful of old sheets that she’d boiled, hung in the sun, and torn up as bandages. She’d bandage Jimmy’s latest cut or graze, around and around, tear the end of the

bandage

into two strips, tie them in a single knot so they wouldn’t rip any further, then wind the two strips around in opposite directions, and do them up with a

granny knot. Last of all, she’d tuck the ends under, so they wouldn’t come undone.

“That’s not too tight is it?” she’d ask, and Jimmy would nod. “Try and keep it on this time,” Mum would tell him.

Ten minutes, and the bandage would be trailing behind Jimmy. The rest of us were always having to stop and wait while he did it up – so it could come off all over again. Then Kate would do it up. “There!” she’d say and give it a little pat. “That’ll stay in place,” and it did.

Mum used to make different poultices: bread, and comfrey root, and porridge to draw his boils. Later there was something called Antiphlogistine. Jimmy sometimes cried when Mum put the poultices on hot. It was even worse when he didn’t cry. The rest of us watched and winced as he sat silent, one of his hands holding the back of Mum’s hand while she put on the poultice and wound the bandage. Sometimes, he’d let Kate do it. He didn’t seem to mind her as much.

Kate always told us that Mum started going funny because Dad wasn’t there. She had to run the farm on her own now, and we were supposed to help her. She kept old Rosie for a house cow, but got rid of the rest of the milking herd. Instead, she bought lambs for fattening, and we ran steers up the back of the farm, black cattle beasts as wild as deer.

“Dry stock,” Mum told us. “They’re less trouble than milking. You can help me by milking old Rosie for the

house, and you can shift the steers around, whenever you’ve got a chance after school and weekends. The more they get used to seeing people and being moved, the easier they are to handle. Quiet stock means better condition.”

Kate started to ask something, and Mum looked at her hard and said quickly, “Better condition means better prices at the sales.

“The lambs won’t be any bother. As soon as they’re fat enough, the drover will collect them. And the same with the steers.” For one moment, I thought Kate was going to ask something else. “It’s going to be less trouble than milking,” Mum said again, but in a little voice, talking to herself rather than us. She often did that now, Kate told us afterwards.

“Mum’s going funny,” Kate said. “Because of Dad.”

S

o, to help Mum, we whistled Blue, piled on Old Pomp, rode him up the back of the farm, and moved the steers from paddock to paddock. They were pretty skittery at first, but Blue showed them who was boss.

One cattle beast put down its head and chased Jimmy, when he fell off Old Pomp, but Blue got it by the tail – that was the heeler in him, Kate said – and swung there till the steer ran bawling after the others. I yanked Jimmy back up, and the steer never gave us any more trouble, but Jimmy always remembered which one it was and pulled faces at it, every time we moved the steers after that. Kate said not to tell Mum, because it would just worry her.

The lambs weren’t any bother. As well as heeler, Blue had a bit of border collie in him, so he could move them around on his own, good-oh. Mum said she wished she could get him to move us around, too. Once, she told him to muster us into the backyard and make us do our jobs, but when Blue tried to strong-eye us, we just stared back and stamped our feet the way we’d seen the old ewes do it. Blue didn’t like that, and you could

see him changing his mind and forgetting. That’s when Kate said he might be missing Dad, too.

At first, we went down to the cowshed and put Rosie in one of the old bails, but it turned out easier to milk her at the back gate. About the time we got home from school, she’d wander up to the house, and wait for somebody to notice her. If we left it too long, she’d stick her head over the hedge and moo to let us know it was time. At first we fought for whose turn it was, but later we got a bit sick of it. We’d say we were late for school, and leave the morning milking for Mum, specially if it was raining.

Mum said we’d have to help her with the vegie garden, now she was on her own, and we did – for a while. Then we got sick of that, and she had to chase us to do a bit of weeding, or to go and pick a feed of silver beet, or dig a bucket of spuds for tea.

Mum went round the lambs each day, and she’d ride our mare, Trixie, up the back and shift the steers with Blue, and she did the gardening. When we felt like it, we’d go and work the steers after school, but time went by, and we got sick of going up every day.

We rode to school on Old Pomp, and pretended he was a Wellington bomber. As the war went on year after year, Old Pomp turned into a Lancaster. Kate was the pilot, and the rest of us squabbled over who was going to be the air gunner in the rear turret. There was another turret in the nose, one on top, and one underneath until we fitted the radar dome there, but

Betty was determined to be the tail gunner. And being Betty, she got her own way.

Jimmy was quite happy in the top turret, firing his guns whether there were enemy planes or not, going, “Ka-Ka-Ka!” at the top of his squeaky voice. When he spun his turret round too fast, he used to fall off and sometimes pull Betty and me with him.

“You fall out of a Lancaster at ten thousand feet,” Kate told him, “and you’ll be squashed over half of Germany.” Jimmy took a bit more care, but soon forgot.

I still wanted to get into the rear turret. “We’ll swap,” I told Betty. “I’ll let you be the navigator and work the radio. And you can aim the bombs and let them drop!” But Betty didn’t fall for it, not even when I told her she could yell out, “Bombs away!”

“You always made me sit at the back when it was just Old Pomp,” she cried, “but now it’s a Lancaster, you all want my turret!”

“Be fair! Give us a turn!”

“You never give me a turn when I wanted to sit up the front.”

“Gave me!” said Kate, who thought grammar was important.

“None of youse give me a turn!” Betty cried.

“Don’t be mean!” I told her.

“S’mine!” You could tell when Betty wasn’t going to give in; it wasn’t just her grammar, but she stuck out her chin.

Kate was more determined than Betty, but she didn’t stick out her chin; and she didn’t get her way only because she was older. Occasionally she’d say something, but other times she just did things without saying a word. You never knew with Kate. Poor Mum, those years when she went funny, she didn’t stand a chance against her.

M

ost days flying to school we had to fight off attacks from Billy Kemp on his pony, Hiccup. Sometimes he was a Messerschmitt 109, sometimes a Spitfire that the Nazis had forced down and captured, it just depended. He’d come hurtling down out of the clouds, or out of the sun. “Ka! Ka! Ka!” his machine guns would go, and we’d be firing back from all four turrets.

Once we’d put in the radar dome, Billy soon worked out that a Lancaster’s belly was its weak spot, so our tail gunner had most of the fun because he had to come up from behind.

Sometimes the Nazi air ace shot us down, sometimes we limped home on three engines, sometimes we bailed out and paddled home in our rubber dinghy. Sometimes we blew Billy Kemp and Hiccup out of the sky: Boom! The tail gunner used to screech, “Gotcha!” as Billy went down in smoke. She tried to claim all the credit.

So it was no wonder we were tired by the time we got home. There was the milking, and the garden, and all the other jobs like feeding the chooks and looking for their eggs, and cleaning the house, tidying our rooms,

and helping Mum bring in the washing, and do the starching, and sprinkling, and ironing.

Jimmy and Betty were old enough to take turns pressing the hankies while the iron was cooling down, and I could be trusted to iron some of the bigger stuff, shorts and shirts and pillow slips, but only Kate and Mum could do the trickier things because of pleats, and scorching. Then there was splitting the kindling, and bringing in the coal, and emptying the ashes into the rubbish hole. Our work was never finished.

Sometimes we forgot we were supposed to go round the lambs or shift the steers and went bird-nesting instead, or we went over to the orchard and filled up on apples or pears. Sometimes we went eeling in the creek, and played hidey-go-seek around the old cowshed and the barn. The buildings smelled dry and empty now, the leg-ropes hanging in the bails, waiting for the cows to come back.

Jimmy said he couldn’t remember what the shed was like with the herd in the yard, the cups going suck-suck on the cows in the bails, and the machine going chug-chug. Betty reckoned she could remember it, but she might just have been making it up. She did that sometimes. She might have been the littlest, but there were no flies on Betty. Mum used to tell her, “For somebody your age, you’ve got the cheek of Old Nick!”

I don’t know about Kate, but I remembered. I stood barefoot on the dry concrete of the yard, listened to the

silence and thought of those forgotten noises, the grassy smell of cows. I didn’t tell anyone, but it made me feel so funny, I kept out of the shed and the barn, most of the time. And I held my breath because somebody had told me that was how to keep off bad luck.

I can’t remember what made Mum go off pop at us – the time she came in from the garden with the bucket of spuds she’d told us to dig for tea in one hand, and the secateurs in her other – but we knew at once she’d had another of her funny ideas.

Mum put down the bucket of spuds with a little grunt and swapped the secateurs into her right hand. We looked up from where we sprawled around the kitchen, looking at “Over the Teacups” in the

Woman’s Weekly

and the pictures in the

Auckland Weekly News

, and squabbling over whose turn it was to milk Rosie.

“I’m fed up with having to dig the garden, plant the spuds, mould them up, dig them, carry them down to the house, wash and peel them, and then have to cook them for you lot, while you lie around the house,

reading

comics, or playing down in the creek when you should be going round the lambs or shifting the steers. Next thing you’ll be expecting me to eat the potatoes for you.

“Why I should have to work my fingers to the bone for a pack of huge, lazy children, I don’t know.

Anyway,

I’ve made up my mind: in future, you can cook for yourselves!” Mum snipped the air with the secateurs, as if she was snipping our ears.

“But if you don’t cook for us, we’ll starve to death,” said Jimmy in his serious voice.

“All the more food for me!” Mum snipped the air again.

Betty stared and said, “But you’re our mother!”

“So what?” Snip! Snip!

“That means you’ve got to cook our food.”

“Who says?”

We looked at each other.

“Because that’s what mothers do,” said Kate. “It says so in the Bible.”

“Where?” Mum took Dad’s old Bible off the top of the wireless and slapped it down on the table. Snip! Snip! “Go on, show me!”

Kate turned at once to Isaiah. “There!” she said. “‘She shall feed her flock like a shepherd,’” she read. “That means you, and we’re your flock.”

“It says ‘He’!” Mum declared. “Not ‘She’!”

“That was for when Dad was here,” Kate said. “It’s you now.”

“Prove it!”

But Kate never gave in easily, specially not with Mum. “You have to feed us because we’re your children. The government says so.”

“Rubbish!”

“I know,” said Jimmy. “We’ll ride into Matamata and tell the policeman you won’t cook us our tea.” You could tell he meant it because his voice went very high.

“That’s different! You wouldn’t really tell on me, would you?” Mum smiled and tried to look friendly, but we remembered the secateurs.

“You bet!” we all said together.

“You’d tell on your poor old mother?”

“Yes!”

“Well, perhaps I’ll cook you your tea after all. I’ll boil these potatoes.”

“Can we have them mashed?” asked Jimmy.

“I suppose so,” Mum said. “So long as you promise you’re not going to tell on me to the policeman.”

“We weren’t going to tell on you,” Jimmy said, “not really,” and ran and put his arms around Mum.

“You were the one who said you were going to tell on me to the policeman, and the rest of you agreed.”

“We were just fooling,” we told Mum as she put down the secateurs so she could wash the potatoes. We made swallowing noises as she put them in a pot and on to the stove to boil, and we watched silently as Kate pinched the secateurs and hid them down her front.

Mum turned round from the stove. “Where are my secateurs?”

“We haven’t seen them!” we all said together.

“You haven’t put any salt in with the potatoes, Mum,” Betty told her.

“If it’s not one thing, it’s another! Why can’t

you

put the salt in? The trouble is, you’re too lazy to do a hand’s turn for yourselves. I’m sure I had them when I came in.”

“You might have left them up the garden,” somebody said, and we ran to have a look. “They’re in the shed,” Kate told her when we came back inside. “They were there all the time. You must have popped them in on your way down to the house.”

“I knew I put them down somewhere,” Mum said. “But I thought I had them when I came into the kitchen with the potatoes.” She thought for a moment. “I’m sure I was going to snip something.” She looked at our ears.

“Well, they were out on the bench where you always put them down. I hung them up on their nail.”

Mum looked at Kate, because she gets up to tricks like that, hiding things that Mum’s just put down for a moment, and then finding them for her somewhere else.

“If I thought for one moment, Kate Costall, that you’d hidden my good secateurs…”

“Why would we do that?” Kate asked Mum. “Are we going to have something to go with the potatoes?”

“When I was a child –” said Mum, and we all looked at Kate.

“When I was a girl –” she said.

“When I was growing up –” said Jimmy, his face very serious.

“When I was your age –” said Betty with a big grin to show she knew it was just a game.

“That’s quite enough of that sort of impertinence to your mother. Do you want to have something to eat

tonight, or don’t you?”

“Yes, please!” we all said together. “What are we going to have with the spuds, Mum?”

In the end, Mum forgot she wasn’t ever going to cook our food again, and we had mashed potatoes with sausages, which we all love, and silver beet which we all hate, so one balanced out the other, as Kate told us. After tea, Mum gave us each a tea-towel and made us dry the dishes while she washed. Then we made her go out to the shed and see her secateurs hanging on their nail above the bench where she must have put them down when she was coming back in from the garden. But she still looked at Kate’s ears, and squinted up her eyes very narrow.

Kate looked innocent and said, “I told you they were there all the time, didn’t I?” And Mum had to say, “I suppose you did.”

But we watched Mum. Every now and again, she went funny. Kate reckoned it was because of Dad not being there.