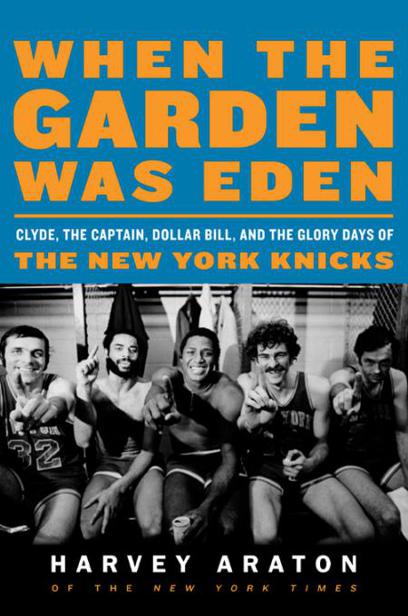

When the Garden Was Eden

Read When the Garden Was Eden Online

Authors: Harvey Araton

GARDEN

WAS EDEN

Clyde, the Captain, Dollar Bill, and the Glory Days of the New York Knicks

HARVEY ARATON

WITH PHOTOGRAPHS BY GEORGE KALINSKY

To Zelda Spoelstra, the Angel of the NBA

,

and to the nurturing women in my life:

Marilyn Araton, Sharon Kushner, Randi Waldman

,

Ruth Albert, Michelle Musler, Sophia Richman

,

and my special love, Beth Albert

PART II: WHEN THE GARDEN WAS EDEN

LAST MAN OUT OF THE TUNNEL WAS WILLIS REED

. The Captain emerged to a rousing ovation at Madison Square Garden and made his stiff-legged way toward his teammates waiting at center court. It was Wednesday night, February 23, 2010, halftime of a thoroughly ordinary Knicks-Bucks game except for the presence of the assembled legends. Bill Bradley and Walt Frazier, Reed’s fellow Knicks in the Hall of Fame, stepped out of the spotlight fringe on either side of the Walter A. Brown world championship trophy—a silver cup that takes more than one man to lift—while Dick Barnett and the beloved “Minutemen” Cazzie Russell and Mike Riordan applauded Reed as if he were coming to their rescue all over again.

This was, in fact, the 40th anniversary of the Knicks’ rise to the summit of pro basketball, and all the men at center court wore varsity jackets custom-made for the occasion: blue-and-white sleeves and 1970 stitched to the left shoulder. Four decades had passed since

“Here comes Willis!”

—since Reed, with a numbed and practically immobilized right leg, hit the Knicks’ first two shots before Frazier and the others followed his lead and buried the Lakers in Game 7 of the NBA Finals.

And yet the celebration seemed tinged with sadness. Teri McGuire appeared for her husband, Dick, the venerable organizational lifer—player, coach, and scout—who had suffered an aortic aneurysm and died earlier that month. Eddie Donovan, the architect of the team fondly known in city basketball circles as the Old Knicks, had suffered a fatal stroke and was represented by his son Sean. Gail Holzman Papelian stood in memory of her father, Red, the wily and streetwise coach of both championship teams. The DeBusschere boys, Peter and Dennis, came for their father, Dave, dead seven years from a sudden heart attack in 2003.

But the legacy lives on. When Frazier stepped to the microphone, the fans in the lower bowl rose, shouting their approval, aiming their cell phones. The man they called Clyde conjured the memories that still, despite the years,

abound and astound

: “I see the Captain coming through the tunnel, I see three of the greatest players ever to play the game—Baylor, West, and Chamberlain—mesmerized by his presence.”

He paused for effect, letting the few fans old and lucky enough to have seen the looks on the faces of the Lakers for themselves linger for just a second longer in the reverie. “I say to myself, ‘We got these guys.’ ”

The disconnect of eras was starkly apparent, 37 years and counting since the Old Knicks had claimed the franchise’s second and last crown, in 1973. A new generation of fans, long suffering and paying staggering prices for an inferior product, constituted that night’s crowd.

In the second half, a team of young players and short-term rentals—filling roster space as the front office readied itself for the unprecedented 2010 free-agent sweepstakes, the Summer of LeBron—played miserably, falling far behind Milwaukee. There would be no glorious comeback, nothing even close to that storied game of November 11, 1972, when Reed, Frazier, and friends ran off the final 19 points to nip the Bucks right here at the Garden. But tonight, as the stands emptied before the end of the fourth quarter, so, too, did the guests of honor retreat from celebrity row, opposite the Knicks’ bench, with only Barnett resisting the urge to bail. Or, as he might have put it:

fall back, baby

. The man who had

TRICKY DICK

stitched into the right sleeve of his commemorative jacket remained in his seat until the final buzzer of the home team’s brutal showing. Sitting alone, Barnett watched through sleepy, expressionless eyes the young men coming off the court, players whose collective achievements pale in comparison with his own but whose individual salaries amount to more than Barnett had earned over his entire career.

“It is what it is,” he said philosophically, staring out at the deserted court as if it were a vandalized cathedral. “And it’s still just a game.”

But when the Captain and Clyde and the rest of the Old Knicks played, when the city and the country convulsed with fury and pain: oh, what a beautiful game it was.

ROOTS

1

DOWN HOME

IT WAS A HOT SUMMER NIGHT IN RUSTON, LOUISIANA

. The air inside Chili’s, a bustling outlet just off I-20, was almost heavy enough to make breathing not worth the effort. The A/C system appeared to be waging the same losing battle as the makeup on the faces of several waitresses. But Willis Reed paid the wet heat no mind. He was much too tickled at tonight’s role reversal. Here, a few thousand miles south of Manhattan, Reed’s best buddy and oldest friend—Howard Brown—was the name brand, the guy with fans clamoring for his attention, the celebrity.

“That’s what happens when you’re a teacher and you have a long career in the same area,” said Reed, former NBA champion and national sports hero. “You know everyone.”

Reed and Brown, both age 67, live not far from here on adjacent properties near the Grambling State University campus where they once shared a dorm room.

“Howard helped me get the land,” Reed said.

“Whenever Willis would come back to visit, he’d stay with me,” Brown said from the seat across from mine. “And about the time he was moving back, he said, ‘If you want to build a house, why not right here?’ ”

The two might as well be brothers, and Reed calls them that. They met in the late 1950s at the all-black Westside High School, a few miles away from Bernice, a 30-minute drive north from Ruston. Willis and Howard both played on Westside High’s basketball team, Reed the star big man and Brown a 6'0" guard who, according to Reed, never met a shot he didn’t like.

Well, only “until it came down to the wire,” said Brown. “Then Coach would say, ‘Get it inside’—which meant ‘Give it to Willis.’ ”

Give it to Willis

. A smirk grew across Brown’s face, and he looked across the table at Reed: “Remember how Coach Stone would hold the bus for you?”

Reed cackled at the memory, while Brown narrated:

“We’d all be there, ready to go, except Willis. There was a guy named Duke who drove the bus, and he’d be looking at Coach, waiting for him to say, ‘Let’s go.’ But then Coach would stand up, put his hands in his pocket, and say, ‘I’ve got to go get my keys.’ He’d go back in the building and wait until he saw Willis walking up to the bus. Then he’d come back on and say, ‘Crank it up, Duke.’ ”

And so the bus would roll with Reed on board, on the way to another all-black school, another audition for a young man destined for stardom in the heart of New York. But all of that had happened decades ago. It was ancient and unknown history to the Chili’s crowd, sweating over their fajitas.

The night manager stopped by our table while making her rounds to comment on my accent, which doesn’t sound too Louisianan.

“He’s here to work on a book,” Brown informed the perky young woman.

“Really,” she said. “What’s it about?”

“This man right here and the basketball team he used to play for,” Brown said. “This is Willis Reed of the New York Knicks; his photo is on your wall.”

He pointed to the entryway of the restaurant and there it was, along with other greats from this area, one uncommonly rich in basketball lore: Bill Russell, a native of Monroe, due east on I-20; Robert Parish, another Celtics Hall of Fame center, out of Shreveport, an hour away on the interstate in the other direction; Karl Malone, who put Ruston’s Louisiana Tech on the college basketball map; Orlando Woolridge, a cousin of Reed’s and a gifted kid who played for Digger Phelps at Notre Dame—on Reed’s recommendation—and later in the NBA; and, of course, Reed himself, who hilariously wasn’t good enough for most of the major universities up north that deigned at the beginning of the sixties to recruit a player or two from the growing pool of African Americans.

In the end, after a brief and uninspired flirtation with the University of Wisconsin and Loyola University of Chicago, Reed was more comfortable moving on down the road to Grambling, where he could play for Fred Hobdy, a protégé of the coaching legend Eddie Robinson, and stay connected with his best friend. Howard Brown might not have been cut out for college basketball, but Reed was more concerned about having a freshman roommate.