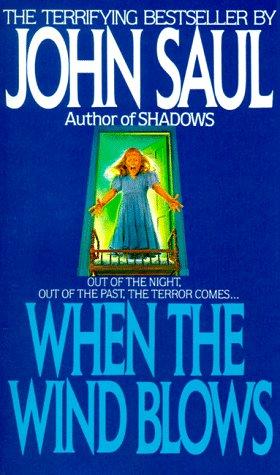

When the Wind Blows

Read When the Wind Blows Online

Authors: John Saul

A sound was coming to her. Her mind began to drift.

Usually it came to her at night, when the wind was blowing. But today was bright and clear; the wind was still.

And yet the sound was there. A baby, crying out for its mother.

Instinctively Diana knelt next to Christie and took the child in her arms. “It’s all right,” she whispered. “Everything’s going to be all right.”

Perplexed, Christie looked into Diana’s eyes. “I

am

all right, Aunt Diana. Really, I am,” Christie insisted.

“But you were crying. I heard you. Good girls never cry. Only bad children cry. They cry. And cry. And then they must be punished …”

By John Saul:

SUFFER THE CHILDREN

PUNISH THE SINNERS

CRY FOR THE STRANGERS

COMES THE BLIND FURY

WHEN THE WIND BLOWS

THE GOD PROJECT

NATHANIEL

BRAINCHILD

HELLFIRE

THE UNWANTED

THE UNLOVED

CREATURE

SLEEPWALK

SECOND CHILD

DARKNESS

SHADOWS

Published by

Dell Publishing

a division of

Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group, Inc

1540 Broadway

New York, New York 10036

Copyright © 1981 by John Saul

All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the written permission of the Publisher, except where permitted by law

The trademark Dell

®

is registered in the U S Patent and Trademark Office

eISBN: 978-0-307-76827-8

v3.1

With appreciation for their

continuing concern for social progress,

this book is dedicated to

Morrie and Joanie Alhadeff

Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Prologue

The wind swept down out of the Rockies like a living thing, twisting its way through the evergreens and aspens, curling through the ravines before spilling out into the valley where, gathering a cargo of dust, it ground eastward, choking the villages and hamlets that dotted the area like prairie-dog colonies.

The people hadn’t known about the wind when they built their towns, but they discovered it soon enough, and, as with all such things, they chose to live with it, ignoring it whenever possible, hiding from it when it got too bad, wryly commenting about it to each other and comparing it favorably to the tornadoes they had left behind when they had migrated westward.

The wind was just one more thing to be lived with, contended with.

And besides, the mines were worth it.

Even the coal mine at Amberton, which, though neither as rich nor as glamorous as the gold and silver mines that seemed to be everywhere but there, was worth the wind.

And so, on a bright spring morning in 1910, the miners made their way into the tunnels of the mine, ignoring the wind, intent only on getting through another day, bringing up the coal to feed the railroad, and returning home to rinse the black dust from their throats with endless shots of whiskey washed down with beer.

Within the mine there was no evidence of either the wind or the spring morning. There was only the flickering yellow glow of the miners’ helmets, the hot, musty, coal-choked air, and the constant undercurrent of fear. Something could go wrong.

In the mines, something always went wrong.

That morning, though, fear mingled with a feeling of optimism, for on that morning they were extending Shaft Number Four, which promised the largest deposit yet discovered in the Amberton mine.

The dynamite had been set the night before, and through the morning the miners worked, checking the fuses, laying the wire, hooking up the blasting machines. Then, finally, they were ready.

They gathered outside the mine, the wind lashing at them as they prepared for the final moment.

The plungers of the blasting machines were shoved downward, and then there was a low rumbling from the depths of the mine.

The miners listened, then grinned at each other.

It was over.

Hundreds of feet down, there was now a pile of rubble, ready to be loaded and hauled to the surface. Picking up their tools, they went back into the mine.

At first no one noticed the water as it seeped through the shattered coal face at the end of Number Four.

When the first miner felt the dampness through his boots, he was more annoyed than worried.

But then the water began rising, and soon the miners realized what had happened.

Somewhere in the depths of the earth, there was a pocket of water, and the blast had disturbed it.

They began hunting for the source of the leak. Someone went to the surface and brought back the shift supervisor and the owner of the mine. Lumber was brought down, and the walls of Number Four

were quickly shored up. But even as they worked, the water began to rise, and soon the miners were wading.

“At the back,” someone cried. “It’s coming in from the back!”

The men surged toward the far reaches of the shaft. Then they saw it.

What had started as a trickle was now a raging torrent, spewing from a gap in the wall.

As they watched, great chunks of coal broke away to be replaced by ice-cold, crystal-clear water that was quickly stained inky black by the pulverized coal over which it flowed.

Suddenly the wall of Number Four caved in, and water rushed over the men, flattening some of them on the floor of the shaft, pinning others to the walls.

The lucky ones were crushed immediately by the crumbling wall of the mine.

The less fortunate drowned in the first few moments of the flood.

For the rest, it was an even more horrible death.

For them, the flood played tricks, picking them up and sweeping them along, then pressing them up near the roof of the mine, where pockets of air were trapped, allowing them to keep their heads above the tide while the icy water numbed their bodies, allowing them to hope for a way out where there was none.

The pressure of the inrushing water began compressing the pockets of air, and for the men trapped against the roof, a new agony began.

Their ears began to hurt, and they swallowed over and over again, trying to clear the pain from their heads. But as more and more water—tons of it—drained into the unnatural shaft that the men had created, the pressure grew; the pain increased.

Some of them plunged into the depths of the water, then fought back up, their fingers clawing instinctively at the roof of the tunnel, trying to find a way

out, even while their lungs filled with water. Soon their struggles ceased.

For the few who grimly clung to life even when they knew it was over, the mine had saved one last torture.

The current stopped flowing, and there was suddenly quiet in the blackness.

Each of the men, unaware that he was not alone in his survival, began to listen in the sudden silence.

None of them knew what he was listening for.

Voices, perhaps.

The voices of friends, calling out for help.

Or the voices of others, rescuers, perhaps.

The sound, when it came, was low. A distant murmur at first that grew and swelled to a chorus of voices. The voices of children, crying in the darkness. Crying for their mothers. Crying a lonely dirge of abandonment.

One by one, the last of the miners began to die. Outside the mine, dusk fell. The wind ceased. Toward the end of the day, it was over.

In the end, all that was left in Number Four was the sound of the children’s voices, still crying, though there was no one left to hear them.

Down the hill from the mine, in a large house that stood alone at the edge of the valley, a woman lay in her bed, pain racking her body.

She was dimly aware that something had happened, that there had been an accident at the mine. And even in the agony of her labor, she knew that her husband had died.

As her baby moved inside her, struggling to release itself into the world, the woman began to know the taste of hatred.

Her husband was dead, and her life was over.

She hadn’t wanted a child, but her wishes hadn’t mattered to her husband—he had insisted. She had

been clever for a while and lied to him about the ways of her body, but it had only been a matter of time before she became pregnant.

And now, as she delivered the tiny gift that her husband would have loved, he had abandoned her, leaving to her only the baby and the mine that had killed him.

The doctor, too, had left her, insisting that he was needed at the mine. The Indian woman who only days before had delivered a baby of her own, was perfectly qualified to care for her, he said. But all the Indian had done was sit by her, muttering to herself in a guttural voice about the curse of this day and the children she thought she could hear crying in the wind.

The woman herself could hear nothing.

Outside, the wind was screaming through the aspens, tearing at the house, rattling windows and plucking at the shingles on the roof.

Inside, the woman screamed silently, refusing to let the Indian woman see the anger and hatred that were growing within her.

As the child came into the world and began crying softly, the Indian crossed herself in the tradition of her religion, while in the depths of her mind she invoked the ancient spirits of her people to protect the child who had the misfortune to be born of this day.

Late that night, as the people of the town gathered in front of the mine to mourn their dead, the woman mourned the birth of her child.

And all through the night, while the wind blew down from the mountains, the sounds of children crying filled the depths of the mine.

For half a century there was no one to hear them.

1