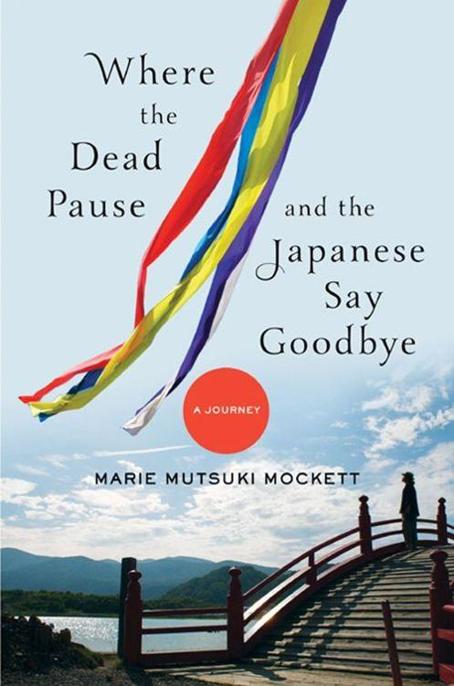

Where the Dead Pause, and the Japanese Say Goodbye: A Journey

Read Where the Dead Pause, and the Japanese Say Goodbye: A Journey Online

Authors: Marie Mutsuki Mockett

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Memoirs, #Social Science, #Death & Dying, #Travel, #Asia, #Japan

FOR MY MOTHER

C

ONTENTS

Once upon a time there was a monster made of water who slept deep in the ocean under a mass of rock. There were people living in homes on top of the rock, delicate creatures whose bodies were made mostly of water, with a little bit of bone and cartilage thrown in. The people liked to eat fish from the ocean, but this didn’t bother the monster. For the most part, it got along fine with the people.

The water monster had an enemy in the giant catfish named namazu, who supported everything—the heavy rock, the monster, and the people and their homes—on his back. Like all catfish,

namazu, who supported everything—the heavy rock, the monster, and the people and their homes—on his back. Like all catfish, namazu had an urgent and continuous desire to twitch, and when he stirred, the rock on his back moved too. Alarmed by the shuddering, the people fled their homes and rushed to the safety of the highest points on the rocks. Then the water monster woke up.

namazu had an urgent and continuous desire to twitch, and when he stirred, the rock on his back moved too. Alarmed by the shuddering, the people fled their homes and rushed to the safety of the highest points on the rocks. Then the water monster woke up.

The monster took a while to suck in its breath—one long, slow inhalation. It sucked the water into its lungs, filling itself until it was so large, it rolled out from its comfortable resting place and veered deep out into the ocean. Now the monster was fully awake and very angry to have been so disturbed. It hurled itself back toward the catfish and the blanket of rock on namazu’s back. The monster devoured some of the people on the rocks, and thrashed others against the sand and stone, before its own body shattered from the

namazu’s back. The monster devoured some of the people on the rocks, and thrashed others against the sand and stone, before its own body shattered from the

impact. The people’s bodies, once broken, could not recover from such fury. But the monster could recongeal.

As night fell, the wily monster lulled the remaining people on the land into the false conviction that all was safe. It was cold and dark, and everyone wanted to go home. They were fairly confident that the monster had gone back under the water, and they went home to make sure that no one had stolen their most valuable possessions. Only then did the monster return—three, four, seven times. More people died, and the houses that had not been destroyed by the previous waves were washed away. Then the people learned that their most valuable possessions had never been the things in their homes.

Because the monster was and is immortal, it knew the cruel pleasure of waiting through the generations. It often struck just as the oldest people who’d last seen it were dying out, and the new people were too young to think it was anything but a legend. But one thing remained consistent. Once it was sighted, the people, old or new, always knew who the monster was. They called it

tsunami

.

W

HERE THE

D

EAD

P

AUSE

,

AND THE

J

APANESE

S

AY

G

OODBYE

O

N

M

ARCH 11, 2011,

I woke to a text from a friend alerting me that Japan had been jolted by an earthquake.

At first I dismissed the news; Japan often has earthquakes. I’m originally from California, and it, too, often has earthquakes. But the urgency of the message intrigued me, and I eventually got out of bed and inspected the news on my computer.

This was no routine earthquake. I checked the epicenter. It was 8.9 or 9.0 on the Richter scale and 130 miles off the coast of Sendai. Reports streamed in that the earthquake had triggered a tsunami, and a graphic of Japan showed an increasingly wide area of impact. The coast of T hoku, the northeast region on Japan’s main island, had been eviscerated. Even though it was morning, my husband poured me a glass of wine from a bottle we’d half drunk the night before, and I sat and watched the Internet, with the radio on in the background.

hoku, the northeast region on Japan’s main island, had been eviscerated. Even though it was morning, my husband poured me a glass of wine from a bottle we’d half drunk the night before, and I sat and watched the Internet, with the radio on in the background.

For thirty-six hours after the earthquake and tsunami, I was unable to get any word from my mother’s family, who own and run a Zen Buddhist temple in Iwaki, a city about eighty-five miles from Sendai on the T hoku coastline. Thirty-six hours does not seem like a very long time given the distance (around seven thousand miles) from Japan to New York, where I lived, and the time difference

hoku coastline. Thirty-six hours does not seem like a very long time given the distance (around seven thousand miles) from Japan to New York, where I lived, and the time difference

(thirteen to fourteen hours, depending on the time of year). But this waiting period felt akin to a week. Friends phoned and sent emails and texts. The attention made me self-conscious. I was not in danger. I called my mother in California and told her not to go to the beach.

Japanese temples, especially older Zen temples like my family’s, are often safely located high up on a hill. This is because a temple is supposed to bring you closer to Buddha and to the gods, who almost always live up in the sky, out of mortal reach. Tsunamis usually impact coastlines, but this particular event was so powerful, the water infiltrated rivers, scaling heights previously considered secure. I watched the images as they were updated, looking for any indication of my family’s fate. A photo came in from Onahama harbor, the seaside port in Iwaki. I picked up the phone again. Nothing.