Where the Stones Sing

Read Where the Stones Sing Online

Authors: Eithne Massey

he white bird, blown up the Liffey by a sharp wind from the east, had a seagull's eye view of Dublin. Below him was a warren of narrow, crooked streets. Many of the timber houses were ramshackle, some of them on the edge of town little more than thatched clay cabins. To the west the river flowed past grey city walls past the yellow cornfields and green woods of the countryside; past the towers and abbeys and castles of its plain from the wild mountains in the west where it had first come out of the earth. Few Dubliners had ever been to those mountains. Dubliners loved to complain about their home town, bemoaning the crowds, the dirt, the crime, but they rarely left it.

he white bird, blown up the Liffey by a sharp wind from the east, had a seagull's eye view of Dublin. Below him was a warren of narrow, crooked streets. Many of the timber houses were ramshackle, some of them on the edge of town little more than thatched clay cabins. To the west the river flowed past grey city walls past the yellow cornfields and green woods of the countryside; past the towers and abbeys and castles of its plain from the wild mountains in the west where it had first come out of the earth. Few Dubliners had ever been to those mountains. Dubliners loved to complain about their home town, bemoaning the crowds, the dirt, the crime, but they rarely left it.

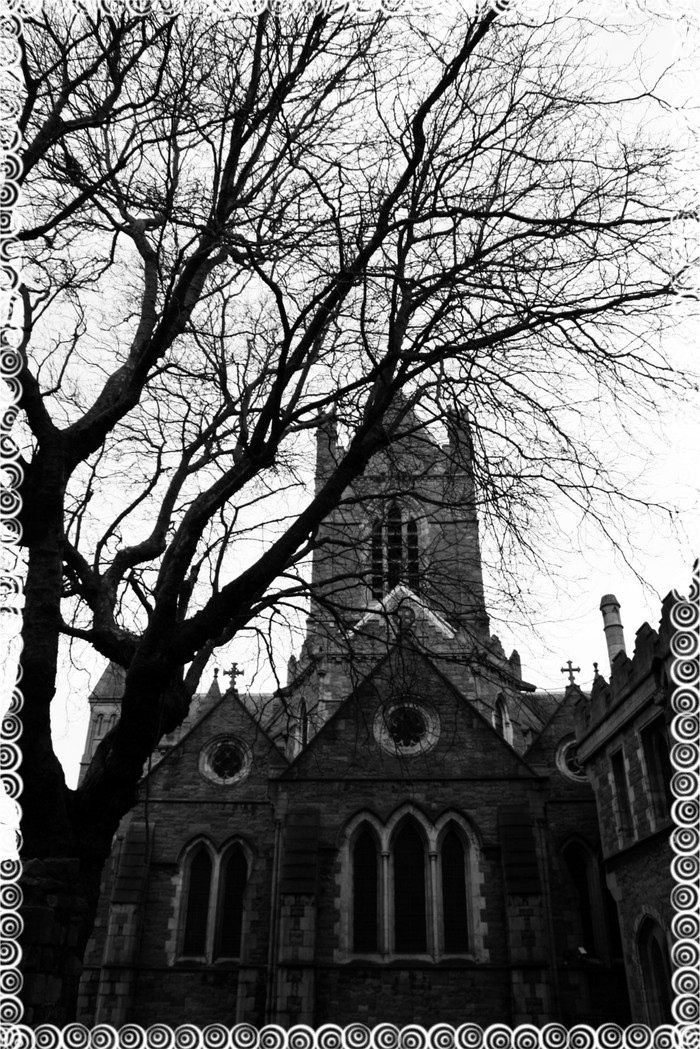

The gull was a Dubliner, and was not going far. He perched on the roof of the great cathedral of Christ Church. The cathedral and the adjoining priory stood on a hill above the river and Fishamble Street wound around the edge of the priory lands. This was where the fish market was. The trestles were piled high with their silvery

wares. At one end of the street was a pile of fish guts, stinking to heaven. The gull swooped and caught a mouthful, avoiding without effort the flapping hands of a fishmonger, who was loading up his wares for the evening. The gull flew west over the cloister of Christ Church to its main gate. There, he settled himself on the priory wall to eat his dinner in the light of the sinking sun. Below him were two ragged children, huddled against the wall. They were quarrelling.

Â

The two children looked like brothers. They were both brown haired and had dark eyes, though the younger one's hair had more red in it and he was thinner and paler than the older boy.

âLet's go now. There is no one around, and I'm tired and cold and hungry,' the younger one was saying. But the other boy shook his head.

âNo point going back to Ymna's if we have no food. There may not be anything to eat if we don't bring a couple of pennies with us. No, let's just try one or two more songs. There might be someone coming out of that inn, and drunk people are often generous.'

âBut they stand around for ages and slobber and talk

rubbish

. And then demand songs from their youth that we don't know,' said the younger one. âI couldn't believe it when that one with the greasy beard demanded

Sumer is icumin in.

It's nearly September.'

âOh, Kai, we can make the words up. If they are far enough

gone they won't notice. We should really wait here until Pa comes back, anyway.'

Kai snorted. âEdward, why are you always so

good?

Who knows when Pa is going to be back? It was dice he was

playing

, wasn't it, this time? With the farmers and shepherds who had come in with their sheep for the market?'

âYes. I'm afraid so. Let's hope they don't look too closely at the dice. Come on, one last song. Then, if we get a penny or so, I promise you we will go buy a pie from one of the stalls before they close them down for the night.'

Kai sighed. âWill we do “Fair Nell”, then?'

The two began to sing, and, having finished his meal of fish guts, the seagull put his head to one side and listened. Not bad, he thought, not bad at all. The children had

beautiful

voices, high and sweet; though there were one or two moments when the voice of the older boy cracked and lost the note.

As they sang, three more boys came along the street. They were dressed identically in the black gowns and white cloaks that marked them as scholars in Holy Trinity Cathedral, known throughout Dublin as Christ Church. The tallest one, thin-faced and cold-eyed, stopped and glared at the singers. âWhat have we here? Fairground children begging in the streets? And singing, disturbing the peace? Hasn't the mayor put out orders that those who do not work are not to be allowed within the city walls?'

The two children stopped singing and the younger one said, âAnd what business is it of yours what we do?'

âMy father says it is the business of every Dublin man, woman and child to make sure that the city laws are kept. And I won't have some beggar give me cheek. If you have any more to say I will stuff your words back down your crowing throat!'

The boy had no sooner finished then he found himself on his back in the mud of the street. Kai was on top of him, pulling his hair hard. Edward dived in an attempt to pull Kai off. But he soon found himself in a fight with the two other boys, who had not hesitated to join in the scrap. Quite a few blows had been exchanged â Kai was particularly pleased with the one that had gone squarely into the thin boy's nose â when the fight was stopped by a stern voice.

âChildren! What's going on? Roland, Jack, I am ashamed of you! And Tom too! You are a disgrace to the priory,

fighting

in the streets like hobbledehoys!'

Two more people had come along the street. The one who had spoken was dressed in a white gown with a black cloak over it and a cross hung around his neck. The voice and the words were angry, but Kai, looking up at him from the ground, thought that this little monk's face looked good natured. As if he were more used to smiling than frowning. The monk was old and quite plump and his hair â what little there was of it â was white. His back was rather stooped, and

he had dark eyebrows over very bright blue eyes.

The three boys stood up and said nothing, simply looked embarrassed as the thin boy tried to mop up the blood from his nose with his sleeve. He was handed a handkerchief by the monk's companion. She was a tall lady, dressed in sombre colours but in very fine cloth, and wearing a cloak trimmed with sable. She had pale gold hair and a sad, calm face.

Now she spoke:

âWe heard singing as we came along the street. Please, will you sing for us again?'

Edward looked meaningfully at Kai. Surely this fine lady would be good for a penny or two at least? They began their song again. To their surprise, the three attackers joined in with the singing, and music filled the street.

When the song was over, the children looked expectantly at the couple. It seemed that the lady was as generous as they had hoped, for she drew her purse out from under her dark violet cloak. But instead of throwing the money into the shawl at their feet, the lady, a shilling in her hand, handed it carefully to Edward.

âThat was beautiful, boys,' she said. âYou both have very fine voices â though yours, I think, is beginning to break. What are your names?'

âWe are of the name Breakwater, and it please you, madam.' It was the younger who spoke. âI am Kai and this is Edward.'

The lady smiled.

âAnd I am Dame Maria de Vincua, and this is my friend, Brother Albert, Canon of the Priory of Christ Church, which is the great building behind this wall. And are you from Dublin? I don't think I have ever seen you here before.'

This time it was the older boy who answered.

âWe do not live here, though we have been in Dublin before now. We have come from the south, with our father. He is a musician, a medical man, and an astrologer. He can pull teeth and cure aches and make love potions and predict the future of any child, any baby born.'

Both children had been trained from an early age to

advertise

their father's wares to passing strangers. But now Edward was sorry he had said anything, for the lady's face changed. She suddenly looked even sadder than before.

Brother Albert interrupted hastily, âThat is most

interesting

, but it is your voices that concern us rather than your father's business. We have been discussing a most pressing need â¦'

âHeigh-ho, what's the to-do here? What mischief has my flesh and blood been up to?'

A dark-haired man came strolling down the street, smiling. Ned Breakwater was exceptionally tall, a feature he sometimes regretted, for it made him more noticeable then he might otherwise have wished to be. But in any company he would have been noticed, for he was a

handsome

man with a glint in his eye and a laugh that rang out

very loud and very often.

âWhat's this? What need is it that my children and not I can fill? 'Tis a strange thought, for, you must believe me, I am a man of many parts. I am an apothecary, a teller of fortunes, a seller of cures and futures. I am a man who can turn my hand to any task I might be set, if it needs a ready wit to do it. I am at your service; Ned Breakwater is my name, though for some reason â¦' his smile grew wider, âI am sometimes called Ned Longshanks.'

He took off his cap and bowed low to the lady, so low that his dark head almost touched the ground.

The canon looked unimpressed and the lady merely lifted one golden eyebrow, as if she was not quite sure if she believed all that Ned Breakwater was saying.

Then Brother Albert said courteously, âThank you for your offer, but I fear we do not need any of those services you mention. It is your children's voices we need, or at least the voice of one of them. This lady here, Dame Maria de Vincua, is as well known for her piety as she is for her wealth in this town of Dublin.'

The lady placed a restraining hand on Brother Albert's arm. âBrother, pray do not â¦'

âNo, do not interrupt me, Maria, it is nothing but the truth.'

He smiled and continued, âDame Maria has lately suffered a most dreadful tragedy, for her son died these two months

gone. Young Philip was a great lover of music, and a most promising singer. For that reason, and for the love of God, the lady has decided to perform an act of great charity. She has made a generous donation to the priory. One of the things she most especially wants is for four choirboys to sing every day in the Chapel of St Mary the White, in the

cathedral

. She will pay for the boys keep and their education as long as they do so. We already have three boys in the choir; these young rascals here. But we have been desperate to find a fourth boy, a boy with a voice like your son's. Would you like to have your child educated and fed, and perhaps have the chance to become a monk himself?'

Ned looked thoughtful.

âHe would live in the priory and be looked after there? I do not know. But perhaps it might serve â what think you, Edward?' He was looking at the older boy.

But now the woman interrupted,âPray you sir, a moment. I think it is the younger child we should wish to have. Your elder son's voice is wonderful, but it is beginning to break. In any case, the younger child is more of an age with the other choirboys. His name is Kai, is it not? A strange name. I have not heard it before.'

There was a silence for a moment. The two children looked at their father with wide eyes. Ned coughed.

âHe is called after the foster brother and seneschal of that most famous and noble king, the legendary King Arthur

of Britain. My wife's people are descended from that great knight, the family is partly Welsh, you know. So it is my little Kai you would wish to have serve at the cathedral. God's teeth, I do not know. What say you, Kai?'

The younger child glared fiercely at Ned Breakwater.

âNo, Pa, no.'

The three boys from the priory had been looking on in surprise. Two of them, thought Kai, looked nice. One had black shining hair and very black eyes, and stood waiting with his head on one side and a faint smile on his face. He reminded Kai of a blackbird; he had the same curious, bright eyes. The other was taller and more solidly built, with fair hair cut in a fringe and wide blue eyes. When they saw that Kai was looking at them they both grinned. It was clear that they harboured no hard feelings about the fight. But the boy who had started the battle, the thin-faced boy the canon had addressed as Roland, looked furious. Now he interrupted angrily, âDon't tell me you want to bring that brat into the priory? To share our lessons and our table? He stinks!'

Brother Albert said sharply, âRoland, hold your tongue. I have often had cause to speak to you about the evil that comes from your mouth. This boy has the voice of an angel. And one does not judge any child of God by the clothes they wear or the money they have in their pockets. Tell me, boy,' he turned to Kai again, âcan you read? And do you know any Latin?'