While the World Watched (21 page)

Read While the World Watched Online

Authors: Carolyn McKinstry

Tags: #RELIGION / Christian Life / Social Issues, #HISTORY / Social History, #BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY / Personal Memoirs

Mourners who overflowed the church stand across the street during funeral services for 14-year-old Carole Robertson, September 17, 1963.

A friend wipes tears from the face of Mrs. Lorene Ware during funeral services for her son Virgil Lamar Ware, September 22, 1963, in Birmingham. Virgil was killed during one of several racially motivated incidents that occurred immediately following the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church bombing.

A seventeen-year-old demonstrator is attacked by a police dog during a Civil Rights march in Birmingham, May 1963.

The Birmingham Fire Department aims high-pressure water hoses at several student marchers during Dr. Martin Luther King’s children’s march in May 1963.

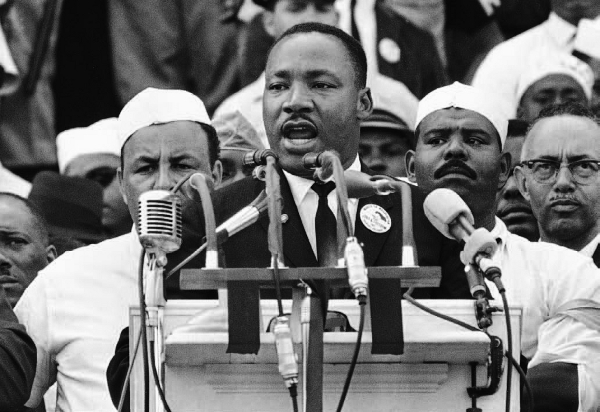

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. addresses marchers during his famous “I Have a Dream” speech at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., August 28, 1963.

Robert F. Kennedy uses a bullhorn to address black demonstrators speaking out for equal rights on June 14, 1963.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. (left), Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth, and Rev. Ralph Abernathy hold a news conference in Birmingham on May 8, 1963.

This stained-glass window was given to the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in 1965 by the people of Wales following the bombing.

Epilogue

For many years I hated those Klan members who bombed my church and killed my four young friends. I wondered how they could do what they did—hurt innocent people because of their skin color. I was angry and confused, and I felt powerless to fix the problem. Hatred, unforgiveness, and bitterness were eating me up, slowly destroying me.

When I was a child and a young adult, it hadn’t really occurred to me that I needed to forgive Klan members. I learned, however, that the hate I held in my heart was hurting me, not them. I cried regularly for twenty years after the bombing. Every time I saw something that reminded me of my friends’ deaths, I relived all the past pain and sorrow. In my anger and hurt, I became dependent on alcohol to numb my inner pain, and I couldn’t sleep at night. I spent years struggling with depression and strained relationships before I was finally able to release this hatred that I harbored in my heart.

I’ll never forget the day I fell on my knees and prayed a specific prayer of surrender: “God, I don’t know what I’ve done to myself—the smoking, the drinking, the sleepless nights. I have become a nervous wreck. Please, God, give me the strength to put it all down. Please fix my body and take away my cravings for alcohol. Please touch me with your healing so I can go forward, knowing I’ve left behind all the unforgiveness in my heart.” That prayer was the beginning of the healing process for me. I made a conscious choice that day to forgive the men who had caused me, my family, my friends, and my community such fear and pain.

I still had much to learn about forgiveness, however—that was only the first step. I didn’t know how it worked, why it healed, what Scripture said about it. I had a lot of growing and maturing to do, and they didn’t happen overnight. Even now, when my memory returns to those dark, frightening times, I must go back to God in prayer and ask him to keep unforgiveness from my heart and to help me see offending people through his eyes, not my own. I know that because of the way Christ has forgiven me, I have no option but to forgive others who have intentionally hurt me and those I love.

At its core, forgiveness is a spiritual act—it’s not something we can do in our own strength. As a Christian woman who has been forgiven by God, I have come to understand that God created all of us—including Bobby Frank Cherry, Thomas Blanton, Robert Chambliss, and Governor George Wallace—even though their hearts overflowed with hate and they allowed that hate to dictate their cruel actions. I have also learned that just as God loves me, he also loves all the people he created. He does not love the crimes they commit, the disrespectful language they use, the bitterness they nurture in their hearts, or the pain and suffering they bring to others. But he loves

them

.

I have often read and reflected on the Bible’s account of Jesus’ crucifixion (see Luke 23:33-43). From the cross, Jesus looked down on the men who crucified him and prayed, “Father, forgive them, for they do not know what they are doing” (Luke 23:34). On each side of Jesus, two common criminals—both deserving of their punishment—had also been nailed to wooden crosses. One thief insulted Jesus. The other criminal, however, rebuked the insulting thief, saying, “This man has done nothing wrong” (Luke 23:41). Then the criminal looked toward the dying Jesus and made a request of deep faith: “Jesus, remember me when you come into your kingdom.” Jesus answered him, “I tell you the truth, today you will be with me in paradise” (Luke 23:42-43).

Jesus forgave the men who crucified him as well as the thief who hung beside him. Pondering that Scripture, as well as other passages throughout the Bible, I came to understand that I, too, needed to forgive those who had hurt me and my family and friends. And that forgiveness was more important for me than for them. It allowed me to move forward with the life God had planned for me. During those times of prayer, Scripture reading, and reflection God seemed to touch my heart. He helped me through the long process of forgiveness, and by his grace I chose to sincerely forgive all those who had so profoundly impacted my young life. Once I forgave, the burden I had carried in my heart lifted. I began to see people the way God sees them. When I stepped into the witness box in that courtroom some forty years after Bobby Cherry had bombed my church, I looked at the man in a different way. Though I was still afraid of him, I could also see another side to him. He looked like an old, tired—albeit hate-filled—grandfather, not the murderer of four innocent Sunday school girls.

I know all of us are capable of evil, but I also believe that as people made in God’s image, there is also good in all of us. Surely we must become intentional in looking for that good.

Loving Our Neighbors

One of the biggest lessons in forgiveness I’ve learned is that God has called me—and each one of us—to care for our neighbors. I try to live by this Scripture verse: “Love does no harm to its neighbor” (Romans 13:10). Jesus himself had a lot to say about the way we treat our neighbors. In addition to the great commission, he also gave us one of the greatest commandments: “Love your neighbor as yourself” (Matthew 22:39). Who are our neighbors? Every person on earth, regardless of color, age, gender, or financial circumstances. What does it mean to love our neighbors? It means forgiving them when they hurt or offend us or someone we love. It means letting go of our anger and resentment against them. It means looking at them with God’s eyes and seeing the goodness in them as creatures made by the almighty Creator God. It means doing our neighbors no harm and treating them as we ourselves want to be treated.

Above all, genuine love does something—it never sits back and watches. Compassion doesn’t require a large committee or a formal, organized approach. You and I can each become a “committee of one.” Hurting people surround us. On each day that God gives us life, we can intentionally strive to help those who are in need. Just imagine what could happen if each one of us reached out every day and touched one person with Christ’s love. One by one, healing would take place in people’s hearts. I believe we can help heal the world with something as simple as daily acts of kindness.

Only about six months after the bomb blast killed my four friends at Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, in the spring of 1964, a young woman in New York City was stabbed and killed in public. Thirty-eight of her neighbors watched her murder but did nothing to help save her life. They opened their windows, looked out at the screaming woman fighting for her life, and simply watched. The woman was twenty-eight-year-old Catherine Genovese. Her neighbors called her “Kitty.” She was returning home late from work one evening and a man grabbed her. Kitty cried out to the watching neighbors for help, but no one responded. The man stabbed her, and she again screamed for help: “He stabbed me! Please help me! Please help me!” The assailant ran away, and Kitty struggled to her feet. When nobody came to her aid, she continued to scream for help: “I’m dying! I’m dying!” But still no one responded. Seeing no opposition, the assailant returned and stabbed Kitty to death—while the world watched. Later, when detectives asked spectators why they didn’t simply dial “0” on their phones and call the police, one person said, “I don’t know.” Another said, “I didn’t want to get involved.”

[86]

If we truly love our neighbors, we will protect them from others who hurt or humiliate them. We will step into their situations and take a stand for them as individuals created by God.

In order to truly love our neighbors, we have to get to know them. As we live and work and commute in the course of our busy everyday lives, we often miss opportunities to truly connect with the people who live around us. We can become so comfortable and protected in our own comfort zones that we fail to reach out to neighbors who are different from us. Genuine love sees beyond the external differences and finds the similarities of another’s heart.

I once heard a beautiful illustration of loving one’s neighbor. A woman in a large neighborhood was sick, had surgery, and came home to recover. Someone placed a huge ice chest on her front steps and filled it with fresh ice every morning. Each day, different people from all over the neighborhood came by and placed casseroles, cakes, soups, and other prepared food in the ice chest for the woman and her family to eat that night. These were anonymous acts of kindness that helped the woman toward physical healing and allowed her to take care of her family. True love gives without needing applause or credit.

The Birmingham Pledge

The city of Birmingham has made its mistakes over the years. People have suffered here because of human cruelties and violence toward one another. As I have pondered the struggle for Civil Rights, I have often asked myself the question

Can anything good come out of Birmingham?

I confess that at times I’ve doubted that anything good could ever come out of my city.

But still I cling to hope. And I know there

is

something good that has come from the pain and suffering of Birmingham’s segregated, violent, dark days: the Birmingham Pledge.

Inspired by the historic events that took place in this city during the Civil Rights movement, Birmingham attorney James E. Rotch composed a statement—a personal commitment to recognize the importance of every individual, regardless of race or color. This commitment became a grassroots movement committed to eliminating prejudice in Birmingham and throughout the world. In the last five years, the Birmingham Pledge has received worldwide recognition, with signatures from tens of thousands of people. In January 2000, a joint resolution of Congress was passed recognizing the Birmingham Pledge. In 2001, President George W. Bush proclaimed September 14–21 as National Birmingham Pledge Week, and he encouraged all citizens to join him in renewing their commitment to fight racism and uphold equal justice and opportunity.

The Birmingham Pledge simply says,

• I believe that every person has worth as an individual.

• I believe that every person is entitled to dignity and respect, regardless of race or color.

• I believe that every thought and every act of racial prejudice is harmful; if it is my thought or act, then it is harmful to me as well as to others.

• Therefore, from this day forward I will strive daily to eliminate racial prejudice from my thoughts and actions.

• I will discourage racial prejudice by others at every opportunity.

• I will treat all people with dignity and respect; and I will strive daily to honor this pledge, knowing that the world will be a better place because of my effort.

[87]

In signing this document, people are pledging to believe in the worth of every person God created and to treat people with respect and dignity. It is also an acknowledgment that racial discrimination—every thought and every cruel action—is harmful, both to the offender and to the recipient. So basic, so simple, and yet so life honoring.

The Gift of Forgiveness

Not long ago I was asked to speak at the Underground Railroad, a historic Civil Rights museum in Cincinnati, Ohio. During my visit I met the senior historian and adviser at the museum, a man in his seventies named Carl Westmoreland. He welcomed me, proudly gave me a personal tour, and showed me the museum’s artifacts. Carl and I had met many years earlier, and he had heard my story of choosing to forgive the men who had killed my four friends.

“After hearing your story, Carolyn,” he said, “I, too, decided to forgive the white men who had set my house on fire. I had been angry for many years, and I’d allowed my heart to fill up with hatred and bitterness. But after listening to you, there was no way I could continue to hold on to that bitterness. I knew I had to forgive.”

Then Carl told me his story. He had owned a house in an impoverished and fairly rough part of downtown Cincinnati. Developers eyed the property and decided they wanted to buy it so they could turn it into apartment buildings. Carl, however, turned down their offer. After many attempts on the developers’ part and Carl’s continual refusal to sell, someone went to Carl’s home while he was at work and set his house on fire. Carl’s eight-year-old son was home alone at the time. The boy managed to get out alive and unharmed, but Carl knew his son could have been burned to death. Over the years Carl hadn’t let go of his anger at this cruel act, and instead had allowed hatred, resentment, and bitterness to grow unchecked in his heart.

That day, during my visit to the Underground Railroad, Carl confessed to me, “When I heard you speak, I realized that if you could forgive those men who had bombed your church, murdered your friends, and almost killed you, I knew I had no choice but to forgive the men who had burned down my house and could have killed my son.”

From Martin Luther King Jr.’s “Where Do We Go from Here?” Speech

I’m concerned about a better world. I’m concerned about justice; I’m concerned about brotherhood; I’m concerned about truth. And when one is concerned about that, he can never advocate violence. For through violence you may murder a murderer, but you can’t murder murder. Through violence you may murder a liar, but you can’t establish truth. Through violence you may murder a hater, but you can’t murder hate through violence. Darkness cannot put out darkness; only light can do that.

And I say to you, I have also decided to stick with love, for I know that love is ultimately the only answer to mankind’s problems. And I’m going to talk about it everywhere I go. I know it isn’t popular to talk about it in some circles today. And I’m not talking about emotional bosh when I talk about love; I’m talking about a strong, demanding love. For I have seen too much hate. I’ve seen too much hate on the faces of sheriffs in the South. I’ve seen hate on the faces of too many Klansmen and too many White Citizens Councilors in the South to want to hate, myself, because every time I see it, I know that it does something to their faces and their personalities, and I say to myself that hate is too great a burden to bear. I have decided to love. If you are seeking the highest good, I think you can find it through love. And the beautiful thing is that we aren’t moving wrong when we do it, because John was right, God is love. He who hates does not know God, but he who loves has the key that unlocks the door to the meaning of ultimate reality.