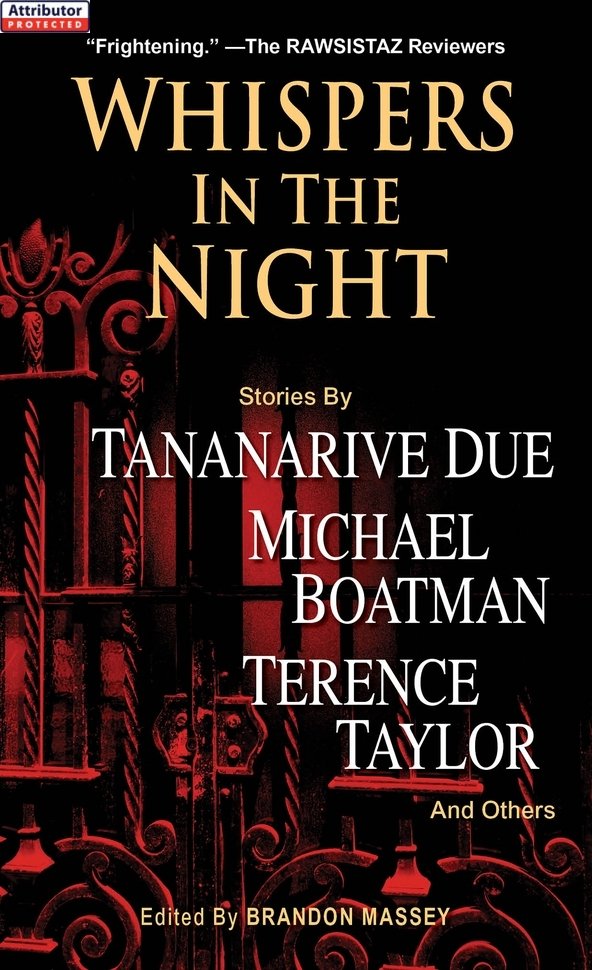

Whispers in the Night

Read Whispers in the Night Online

Authors: Brandon Massey

ALSO BY BRANDON MASSEY

Cornered

Â

Don't Ever Tell

Â

The Other Brother

Â

Twisted Tales

Â

Within the Shadows

Â

Dark Corner

Â

Thunderland

Â

Â

The Dark Dreams Anthologies

Â

Dark Dreams

Â

Voices From the Other Side

Â

Whispers in the Night

Â

The Ancestors

WHISPERS IN THE NIGHT

Edited by BRANDON MASSEY

KENSINGTON PUBLISHING CORP.

http://www.kensingtonbooks.com

http://www.kensingtonbooks.com

All copyrighted material within is Attributor Protected.

Table of Contents

ALSO BY BRANDON MASSEY

Title Page

INTRODUCTION

Summer

- Tananarive Due

Scab

- Wrath James White

And Death Rode with Him

Are You My Daddy?

To Get Bread and Butter

Dream Girl

My Sister's Keeper

The Wasp

Hell Is for Children

Flight

Hadley Shimmerhorn: American Icon

Nurse's Requiem

Wet Pain

The Taken

Mr. Bones

Rip Crew

Power and Purpose

The Love of a Zombie Is Everlasting

Ghostwriter

ABOUT THE CONTRIBUTORS

Copyright Page

Title Page

INTRODUCTION

Summer

- Tananarive Due

Scab

- Wrath James White

And Death Rode with Him

Are You My Daddy?

To Get Bread and Butter

Dream Girl

My Sister's Keeper

The Wasp

Hell Is for Children

Flight

Hadley Shimmerhorn: American Icon

Nurse's Requiem

Wet Pain

The Taken

Mr. Bones

Rip Crew

Power and Purpose

The Love of a Zombie Is Everlasting

Ghostwriter

ABOUT THE CONTRIBUTORS

Copyright Page

INTRODUCTION

W

ell, well, well. Here we are again. And as the old saying goes, the third time's the charm.

ell, well, well. Here we are again. And as the old saying goes, the third time's the charm.

If you're a newbie to the

Dark Dreams

series, here's a quick overview of what it's all about: a collection of horror and suspense short fiction, following no particular theme, with all of the stories written exclusively by black writers, established, upcoming, and those seeing their work in print for the first time ever.

Dark Dreams

series, here's a quick overview of what it's all about: a collection of horror and suspense short fiction, following no particular theme, with all of the stories written exclusively by black writers, established, upcoming, and those seeing their work in print for the first time ever.

In the three years since the first volume in the series was published, we've seen, happily, more horror/ suspense fiction by black writers on bookstore shelves, much of it produced by

Dark Dreams

alumni. Tananarive Due, L.A. Banks, and Robert Fleming have given us memorable novels and short story collections. Evie Rhodes has been growing an audience, with works such as

Expired

and

Criss Cross.

Gregory Townes earned much-deserved acclaim for

The Tribe

, his self-published debut. Speaking of self-published horror novels by black writers, in fact, there are a

ton

of them, and it will be interesting to see how many find their way inside a major publisher's catalog in the near future.

Dark Dreams

alumni. Tananarive Due, L.A. Banks, and Robert Fleming have given us memorable novels and short story collections. Evie Rhodes has been growing an audience, with works such as

Expired

and

Criss Cross.

Gregory Townes earned much-deserved acclaim for

The Tribe

, his self-published debut. Speaking of self-published horror novels by black writers, in fact, there are a

ton

of them, and it will be interesting to see how many find their way inside a major publisher's catalog in the near future.

All of this is good. Many eyes have been opened in the past few years; people are beginning to see that black writers really

can

write horror stories. But there is still much work to be done. Personally, I'm looking forward to the day when I'm not referred to as the Black Stephen King or Dean Koontz; I'm looking forward to the day when I can give a speech to a group of readers and don't have to justify why I write the stories that I do.

can

write horror stories. But there is still much work to be done. Personally, I'm looking forward to the day when I'm not referred to as the Black Stephen King or Dean Koontz; I'm looking forward to the day when I can give a speech to a group of readers and don't have to justify why I write the stories that I do.

More important: I'm looking forward to the day when

any

black writer can pen a tale of horror and suspense, and can discuss it with readers without apologies or undue explanation, without being likened to being merely a black version of a white author, without being viewed with suspicion or even fear.

any

black writer can pen a tale of horror and suspense, and can discuss it with readers without apologies or undue explanation, without being likened to being merely a black version of a white author, without being viewed with suspicion or even fear.

Bottom lineâI'm looking forward to seeing genuine

respect

accorded to the brothers and sisters who choose to write in this oft-maligned field. The

Dark Dreams

series is a collective effort by those of us who love the genre to nurture that love in others, too. A grand ambition, to be sure. The only way for us to achieve it is to deliver stories that challenge, thrill, educate, entertain, and delight readers.

respect

accorded to the brothers and sisters who choose to write in this oft-maligned field. The

Dark Dreams

series is a collective effort by those of us who love the genre to nurture that love in others, too. A grand ambition, to be sure. The only way for us to achieve it is to deliver stories that challenge, thrill, educate, entertain, and delight readers.

The first two

Dark Dreams

books broke new ground in the genre; I truly believe that in this, the third volume, we may have the finest stories yet. This is no easy feat, considering how well received the first two books have been. If you've been following the series from the beginning, you'll notice that many of the writers from the previous collections have appeared yet again in this one. There's a reason for this, and it's quite simple: time and again, they've given me the best stories.

Dark Dreams

books broke new ground in the genre; I truly believe that in this, the third volume, we may have the finest stories yet. This is no easy feat, considering how well received the first two books have been. If you've been following the series from the beginning, you'll notice that many of the writers from the previous collections have appeared yet again in this one. There's a reason for this, and it's quite simple: time and again, they've given me the best stories.

The celebrated Tananarive Due, for example, has participated in all three anthologies. “Danger Word,” her story in the first book, which she cowrote with her husband, Steven Barnes, was an apocalyptic zombie tale; her second story, “Upstairs,” was a gripping tale of psychological “real world” horror about a little girl who has a secret relationship with a serial killer hiding out in her family's attic. And her entry here, “Summer,” is another grabber, a story about a young mother struggling to raise her infant daughter one sweltering summer on the swampâwhen her child-rearing troubles are suddenly eased by an otherworldly visitor....

Other three-time contributors include Christopher Chambers, back with “Mr. Bones,” a story set in the days of black minstrels on the chitlin circuitâand brought into modern times with a chilling, thought-provoking twist. L.R. Giles uses the recent megachurch phenomenon as the background of his “Power and Purpose,” an aptly titled piece about a gifted psychic who may be the only one able to save a popular preacher. Anthony Beal returns with “And Death Rode With Him,” a puzzlingâand ultimately revealingâstory about a bar in the Southwest desert, where the drinks are bad and the patrons never seem to leave. Rickey Windell George, always reliable for a shocker of a tale, will knock you out with “Hell Is for Children,” a grisly account of a mother doing her best to raise her child under the most trying of circumstances (only readers with strong stomachs should dare to read this one).

Lawana James-Holland is back with a signature story of history and horror in “Flight,” following the adventures of a black man living with Native Americans in the frontier daysâwhen mystical beasts possibly roamed the land. In “Rip Crew,” B. Gordon Doyle uses the hard-hitting language and culture of the streets to pull us into a shadowy world inhabited by violent gangs and bizarre sex cults. Chesya Burke questions how far one should go to save a wayward sister in “My Sister's Keeper.” And Terence Taylor resurrects the still-fresh tragedy of Hurricane Katrina to inform his unforgettable “WET PAIN,” a story of racism, friendship. . . and malevolent entities that feed on human misery.

Those are the members of the “three-time” team. But we've also got writers returning for a second tour of dark dreaming duty. In “The Wasp,” Robert Fleming tells the story of a woman who tries to use the legal system to escape her abusive husbandâand when it fails and even turns on her, as a last resort she takes a most extreme way out. Maurice Broaddus plumbs questions of God and the Devil in “Nurse's Requiem,” as a young Christian man works at a deteriorating nursing home in a quest to prove his faith. Michael Boatman takes another break from his acting work to demonstrate again that he's a multitalented artist, in the satiric zombie tale “Hadley Shimmerhorn: American Icon.”

But

Dark Dreams

isn't just about prior contributors coming back to entertain us and challenge us anew; it's also a venue for new voices and first-timers to the series. Wrath James White, known in the horror small-press community for his searing visions of terror, hits a home run with “Scab,” a stunning story of a dark-skinned black man tragically haunted by the mocking, derisive voices of his youth, when it wasn't considered “in” to have a dark complexion. Lexi Davis dishes up a load of laughs in “Are You My Daddy?” about a young man who just can't get away from the responsibility of serving as a child's fatherâa kid gifted in ways that'll make your head spin.

Dark Dreams

isn't just about prior contributors coming back to entertain us and challenge us anew; it's also a venue for new voices and first-timers to the series. Wrath James White, known in the horror small-press community for his searing visions of terror, hits a home run with “Scab,” a stunning story of a dark-skinned black man tragically haunted by the mocking, derisive voices of his youth, when it wasn't considered “in” to have a dark complexion. Lexi Davis dishes up a load of laughs in “Are You My Daddy?” about a young man who just can't get away from the responsibility of serving as a child's fatherâa kid gifted in ways that'll make your head spin.

With “Dream Girl,” Dameon Edwards, in his first major publication, explores the question that black women seeking a black man continually ask, “Where are all the good brothers?” According to this unusual story, they just might be hanging out at the strip clubsâwith a girl from their dreams who materializes from thin air.... Tenea Johnson delves into a fascinating racial issue in “The Taken,” about a pro-black group that abducts a number of affluent white adultsâand stows them on a ship, in a reenactment of the infamous and harrowing Middle Passage that brought millions of Africans to America.

Newcomer Tish Jackson shows a deft touch for tongue-in-cheek comedy and horror in “The Love of a Zombie Is Everlasting,” perhaps the most original zombie story I've yet to read. And Randy Walker gives us a fresh twist on the obsessive-compulsive, weirdo writer idea with “To Get Bread and Butter,” about an author who makes

Monk

(a TV show featuring a famously eccentric detective) look positively normal by comparison.

Monk

(a TV show featuring a famously eccentric detective) look positively normal by comparison.

There's a startling breadth of work here. If you have a taste for the imaginative, the suspenseful, the horrific, or the just plain bizarre, you'll find something (hopefully,

much

) that you'll enjoy.

much

) that you'll enjoy.

And remember, you'd better keep that night-light on . . .

Summer

Tananarive Due

D

uring the baby's nap time, a housefly buzzed past the new screen somehow and landed on Danielle's wrist while she was reading

Us Weekly

on the back porch. With the Okeepechee swamp so close, mosquitoes and flies take over Graceville in summer.

uring the baby's nap time, a housefly buzzed past the new screen somehow and landed on Danielle's wrist while she was reading

Us Weekly

on the back porch. With the Okeepechee swamp so close, mosquitoes and flies take over Graceville in summer.

“Well, I'll be damned,” she said.

Most flies zipped off at the first movement. Not this one. The fly sat still when Danielle shook her wrist. Repulsion came over her as she noticed the fly's spindly legs and shiny coppery green helmet staring back at her, so she rolled up the magazine and gave it a swat. The fly never seemed to notice Angelina Jolie's face coming. Unusual for a fly, with all those eyes seeing from so many directions. But there it was, dead on the porch floorboards.

Anyone who says they wouldn't hurt a fly is lying

, Danielle thought.

, Danielle thought.

She didn't suspect the fly was a sign until a week later, when it happened againâthis time she was in the bathroom clipping her toenails on top of the closed toilet seat, not in her bedroom, where she might disturb Lola during her nap. A fly landed on Danielle's big toe and stayed put.

Danielle conjured Grandmother's voice in her memoryâas she often did when she noticed the quiet things Grandmother used to tell her about. Grandmother had passed three summers ago after a stroke in her garden, and now that she was gone, Danielle had a thousand and one questions for her. The lost questions hurt the most.

Anything can happen once,

Grandmother used to say.

When it happens twiceâlisten. The third time may be too late.

Anything can happen once,

Grandmother used to say.

When it happens twiceâlisten. The third time may be too late.

It was true about men, and Danielle suspected it was true about the flies, too.

Once the second fly was deadâagain, almost as if it had made peace with leaving this world on the sole of her slipperâDanielle wondered what the flies meant. Was someone trying to send her a message? A warning? Whatever it was, she was sure it was something bad.

Being in the U.S. Army Reserves, her husband, Kyle, didn't like to look for omens. He only laughed when she talked about Grandmother's beliefs, not that Kyle was around in the summer to talk to about anything. His training was in summers so it wouldn't interfere with his job as county school bus supervisor. Last year, he'd been gone only a couple of weeks, but this time he was spending two long months at Fort Irwin in California. He was in training exercises, so the only way to reach him was in a real emergency, through the Red Cross. She hadn't spoken to him in three weeks.

Kyle had been in training so long, the war had almost come and gone. But he still might get deployed. He'd reminded her of that right before he left, as if she'd made a promise she and Lola could do fine without him. What would she do if she became one of those Iraq wives? Life was hard enough in summer already, without death hanging over her head, too.

With Grandmother gone from this earth and Kyle in California, Danielle had never been so lonely. She felt loneliest in the bathroom. Maybe the small space was too much like a prison cell. But she didn't fight the feeling. Her loneliness felt comfortable, familiar. She wouldn't have minded sitting with the sting awhile, feeling sorry for herself, staring at the dead fly on the black and white tile. Wondering what its message had been.

But there wasn't enough time for that. Lola was awake, already angry and howling.

Â

Â

Long before the bodies were found, Grandmother always said the Okeepechee swampland was touched by wrong. Old Man McCormack sold his family's land to developers last fall, and Caterpillar trucks were digging a man-made lake in the soggy ground when they uncovered the bones. And not just a few bones, either. The government people and researchers were still digging, but Danielle had heard there were three bodies, at last count. And not a quarter mile from her front door!

Grandmother had told her the swampland had secrets. Lately, Danielle tried to recall more clearly what Grandmother's other prophecies had been, but all she remembered was Grandmother's earthy laughter. Danielle barely had time to fix herself a bowl of cereal in the mornings, so she didn't have the luxury of Grandmother's habits: mixing powders, lighting candles, and sitting still to wait. But Danielle believed in the swampland's secrets.

All her life, she'd known Graceville was a hard place to live, and it was worse on the swamp side. Everyone knew that. People died of cancer and lovers drove each other to misery all over Graceville, but the biggest tragedies were clustered on the swamp sideânot downtown, and not in the development called The Farms where no one did any farming. When she was in elementary school, her classmate LaToya's father went crazy. He came home from work one day and shot up everyone in the house; first LaToya, then her little brothers (even the baby), and her mother. When they were all dead, he put the gun in his mouth and pulled the triggerâwhich Danielle wished he'd done at the start. That had made the national news.

Sad stories had always watered Graceville's backyard vegetable gardens. Danielle's parents used to tell her stories about how awful poverty was, back when sharecropping was the only job for those who weren't bound to be teachers, and most of their generation's tragedies had money at their core. That wasn't so true these days, no matter what her parents said. Even people on the swamp side of Graceville had better jobs and bigger houses than they used to. They just didn't seem to build their lives any better.

Danielle had never expected to raise a baby in Graceville, or live in her late grandmother's house with an Atlanta-born husband who should know better. The thought of Atlanta only six hours north nearly drove her crazy some days. But Kyle Darren Richardson was practical enough for the both of them. Coolheaded. That was probably why the military liked him enough to invest so much training.

Do you know how much houses cost in Atlanta? We'll save for a few more years, and then we'll go. Once my training is done, we'll never be hurting for money, and we'll live on a base in Germany somewhere. Then you can kiss Graceville good-bye.

Do you know how much houses cost in Atlanta? We'll save for a few more years, and then we'll go. Once my training is done, we'll never be hurting for money, and we'll live on a base in Germany somewhere. Then you can kiss Graceville good-bye.

In summer, with Kyle gone, she was almost sure she was just another fool who never had the sense to get out of Graceville. Ever since high school, she'd seen her classmates with babies slung to their hips, or married to the first boy who told them they were pretty, and she'd sworn,

Not me.

All of those old friendsâeach and every oneâhad their plans, too. Once upon a time.

Not me.

All of those old friendsâeach and every oneâhad their plans, too. Once upon a time.

Danielle wasn't sure if she was patient and wise, or if she was a tragedy unfolding slowly, one hot summer day at a time.

Â

Â

Lola cried harder when she saw her in the doorway. Lola's angry brown-red jowls were smudged with dried flour and old mucus. Sometimes Lola was not pretty at all.

Danielle leaned over the crib. “Go back to sleep, Lola. What's the matter now?”

As Danielle lifted Lola beneath her armpits, the baby grabbed big fistfuls of Danielle's cheeks and squeezed with all her might. Then she shrieked and dug in her nails. Hard. Her eyes screwed tight, her face burning with a mighty mission.

Danielle cried out, almost dropping all twenty pounds of Lola straight to the floor. Danielle wrapped her arm more tightly around Lola's waist while the baby writhed, just before Lola would have slipped. The baby's legs banged against the crib's railings, but Danielle knew her wailing was only for show. Lola was thirteen months old and a liar already.

“

No

.” Danielle said, keeping silent the

you little shit bag

. “

Very

bad, Lola.”

No

.” Danielle said, keeping silent the

you little shit bag

. “

Very

bad, Lola.”

Lola shot out a pudgy hand, hoping for another chance at her mother's face, and Danielle bucked back, almost fast enough to make her miss. But Lola's finger caught the small hoop of the gold earring in Danielle's right earlobe and pulled, hard. The earring's catch held at first, and Danielle cried out as pain tore through. Danielle expected to see droplets of blood on the floor, but she only saw the flash of gold as the earring fell.

Lola's crying stopped short, replaced by laughter and a triumphant grin.

Anyone who says they wouldn't hurt a fly is lying.

If Lola were a grown person who had just done the same thing, Danielle would have knocked her through a window. Rubbing her ear, she understood the term

seeing red

, because her eyes flushed with crimson anger. Danielle almost didn't trust herself to lay a hand on the child in her current state, but if she didn't Lola's behavior would never improve. She grabbed Lola's fat arm firmly, the way her mother had said she should, and fixed her gaze.

seeing red

, because her eyes flushed with crimson anger. Danielle almost didn't trust herself to lay a hand on the child in her current state, but if she didn't Lola's behavior would never improve. She grabbed Lola's fat arm firmly, the way her mother had said she should, and fixed her gaze.

“

No

.” Danielle said. “Trying to hurt Mommy is

not

funny.”

No

.” Danielle said. “Trying to hurt Mommy is

not

funny.”

Lola laughed so hard, it brought tears to her eyes. Lola enjoyed hurting her. Not all the time, but sometimes. Danielle was sure of it.

Danielle's mother said she was welcome to bring Lola over for a few hours whenever she needed time to herself, but Mom's joints were so bad that she could hardly pull herself out of her chair. Mom had never been the same since she broke her hip. She couldn't keep up with Lola, the way the child darted and dashed everywhere, pulling over and knocking down everything her hands could reach. Besides, Danielle didn't like what she saw in her mother's eyes when she brought Lola over for more than a few minutes:

Jesus, help, she can't even control her own child.

Jesus, help, she can't even control her own child.

Danielle glanced at the Winnie the Pooh clock on the dresser. Only two o'clock. The whole day stretched to fill with just her and the baby. Danielle wanted to cry, too.

Kyle told her maybe she had postpartum depression like the celebrity women she read about. But her family had picked cotton and tobacco until two generations ago, and if they could tolerate that heat and work and deprivation without pills and therapy, Danielle doubted her constitution was as fragile as people who pretended to be someone else for a living.

Lola could be hateful, that was all. That was the truth nobody wanted to hear.

Danielle had tried to conceive for two years, and she would always love her daughterâbut she didn't like Lola much in summer. Lola had always been a fussy baby, but she was worse when Kyle was gone. Kyle's baritone voice could snap Lola back to her sweeter nature. Nothing Danielle did could.

Â

Â

“She still a handful, huh, Danny?”

“That's one word.”

Odetta Mayfield was the only cousin Danielle got along with. She was ten years older, so they hadn't started talking until Grandmother's funeral, and they'd become friends the past two years. The funeral had been a reunion, helping Danielle sew together pieces of her family. Odetta's husband had been in the army during the first Iraq war and come back with a girlfriend. They had divorced long ago and her son was a freshman at Florida State, so Odetta came by the house three or four times a week. Odetta had no one else to talk to, and neither did she. If not for her cousin and her mother, Danielle might be a hermit in summer.

Odetta bounced Lola on her knee while the baby drank placidly from a bottle filled with apple juice. Seeing them together in the white wicker rocker, their features so similar, Danielle wanted to beg her cousin to take the baby home with her. Just for a night or two.

“Did she leave a mark on my face?”

“Can't see nothing from here,” Odetta said. But Danielle could feel two small welts rising alongside her right cheekbone. She dabbed her face with the damp kitchen towel beside the pitcher of sugar-free lemonade they had decided to try for a while. The drink tasted like chemicals.

“People talk about boys, but sometimes girls are just as bad, or worse,” Odetta said. “We went through the same mess with Rashan. It passes.”

Danielle only grunted. She didn't want to talk about Lola anymore. “Anything new from McCormack's place?” she asked, a sure way to change the subject. Odetta worked as a clerk at City Hall, so she had a reason to be in everybody's business.

“Girl, it's seven bodies.

Seven

.”

Seven

.”

Seven bodies left unaccounted for, rotting in swampland? The idea made Danielle's skin feel cold. Mass graves always reminded her of the Holocaust, a lesson that had shocked her in seventh grade. She'd never looked at the world the same way after that, just like when Grandmother first told her about slavery.

“My mother still talks about the civil rights days, the summer those college kids tried to register sharecroppers on McCormack's land. He set those dogs loose on them,” Danielle said.

“Unnnnnhhhhh-hnnnnhhhhh . . .” Odetta said, drawing out the indictment. “Sure did. That's the first thing everybody thought. But the experts from Tallahassee say the bones are older than forty-odd years. More like a hundred.”

“Even so, how are seven people gonna be buried out on that family's land? There weren't any Indians living there. Shoot, that land's been McCormack Farm since slavery. I bet those bones are from slave times and they just don't wanna say. Or something like Rosewood, with a bunch of folks killed and people kept it quiet.”

“Unnnhhhh-hhnnnnnhhh,” Odetta said. She had thought of that, too. “We may never know what happened to those people, but one thing we

do

knowâkeep off that land.”

do

knowâkeep off that land.”

“That's what Grandmother said, from way back. When I was a kid.”

“I know. Mama, too. Only a fool would buy one of those plots.”

The McCormack Farm was less than a mile from Danielle's grandmother's house, along the unpaved red clay road the city called State Route 191, but which everyone else called Tobacco Road. Tobacco had been the McCormacks' business until the 1970s.

Another curse to boot

, Danielle thought. She drove past the McCormacks' faded wooden gate every time she went into town, and the gaudy billboard advertising

LOTS FOR SALEâAS LOW AS

$150,000. The mammoth, ramshackle tobacco barn stood beside the roadway for no other reason than to remind everyone of where the McCormack money had come from. Danielle's grandfather had sharecropped for the McCormacks, and family lore said her relatives had once been their slaves.

Another curse to boot

, Danielle thought. She drove past the McCormacks' faded wooden gate every time she went into town, and the gaudy billboard advertising

LOTS FOR SALEâAS LOW AS

$150,000. The mammoth, ramshackle tobacco barn stood beside the roadway for no other reason than to remind everyone of where the McCormack money had come from. Danielle's grandfather had sharecropped for the McCormacks, and family lore said her relatives had once been their slaves.

Other books

Blindsided (The Fighter Series Book 1) by Matson, TC

The War I Always Wanted by Brandon Friedman

Lovers Meeting by Irene Carr

Torian Reclamation 2: Flash Move by Andy Kasch

INSOMNIAC: ALAN SMITH #2 (Alan Smith series) by ARKOPAUL DAS

The Prophecy of Shadows by Michelle Madow

A Darkness More Than Night by Michael Connelly

The Games by Ted Kosmatka

The Complete Works of William Shakespeare In Plain and Simple English (Translated) by SHAKESPEARE, WILLIAM