White Shadow (2 page)

Authors: Ace Atkins

DATELINE: TAMPA

When I think of Tampa, I remember the tunnels winding their way under the old Latin District of Ybor City; unlit, partially caved-in airless holes beneath Seventh Avenue, where the steady stream of Buicks and Hudsons overhead has become the pounding bass music from flashy sedans and tricked-out trucks. Most people will tell you the caves are the stuff of urban legend. Others will tell you they were, without doubt, the passageways for bootlegger Charlie Wall to run his liquor to bars during Prohibition. In back booths of West Tampa Cuban cafés, you still might hear hushed conversations about Charlie: the white linen suit, the silver dollars he threw to poor orphans, the old bolita racket, and the jokes he told to U.S. senators during the Kefauver hearings of 1950. (That’s when every elected official was on the take and right before I got out of the army and headed out to work for Hampton Dunn at the

Times

with a single gray suit, a studio apartment, and barely enough change for cabs.)

Times

with a single gray suit, a studio apartment, and barely enough change for cabs.)

When I knew Charlie Wall, he was the old-timer sitting at the edge of the bar—The Dream or The Turf or The Hub—holding court, telling us about the old days and all about running the sheriff and the mayor and the newspapers. He’d punctuate the tales with a sip of those big bastard Canadian whiskey highballs, and launch into another one.

All those stories we wrote about Charlie were cut into clips and have turned yellow and brittle if they exist at all. Maybe they are in landfills or stacked in forgotten warehouses or rotting barns among the molded dung heaps or wrapping Christmas ornaments or just disintegrated into the dirt. But I still remember putting out those tales, and how the energy and pulse of the

Times

newsroom was like nothing I’d ever known.

Times

newsroom was like nothing I’d ever known.

The old King, the White Shadow as he was called by the superstitious Latins, was dead. His throat cut. Birdseed left splattered on the floor by his favorite reading chair in that big bungalow on Seventeenth Avenue.

Being someone who sits and talks in cafés, I know how the conversation always winds back to Charlie Wall, Mafia boss Santo Trafficante, and the murders during what we called the Era of Blood. Shotgun attacks in back alleys, restaurants, and palm tree-lined streets.

You were there? Weren’t you?

You were there? Weren’t you?

The names: Joe Antinori, JoJo Cacciatore, Joe “Pelusa” Diaz, Scarface Johnny Rivera. The places: the Centro Asturiano, the Big Orange Drive-In, the Sapphire Room, Jake’s Silver Coach Diner.

I tell them it’s all gone now. They’re all gone now. That was another lifetime ago.

But, inside, I know that on certain times of night and in certain neighborhoods, it’s as if the old world still exists. You have to use your imagination and watch Tampa through a patchwork of images and places, but those ghosts still live.

In the old Ybor cemetery, a marble bust dedicated to a long-dead waiter stands with carved napkin folded across his forearm—still ready to serve the city’s elite. But instead of orders and the clatter of plates and silverware, the only sound comes from the interstate overpass or the occasional gunshot or crying baby from inside the barred windows of the faded, candy-colored casitas where cigar workers once lived.

Nearby, you still hear that lonely train whistle as the phosphate cars rumble along the track from the old Switchyards. And you can see Santo Trafficante Jr. in the corner of the Columbia Restaurant, down the road from the tunnels, sipping on a café con leche—the waiters afraid to refill his cup for fear something hot would spill on the mob boss’s hands.

On the other side of the peninsula of Tampa, separated by old Hillsborough Bay, the other ghosts live in postwar neighborhoods like Sunset Park and the Anglo world of Palma Ceia. You remember how they all would meet on the neutral ground of the grand hotels downtown—now replaced with anonymous glass office buildings—where jazz piano seemed to fill every street.

You think about driving down to the Fun-Lan on Hillsborough and watching Grace Kelly or Gregory Peck or Richard Widmark light up the drive-in screen while those green-and-white electric thunderstorms rolled and threatened far off in the bay, and the city streets smelled of ozone and salt.

That world gone now.

Both sides of Charlie Wall’s tunnels are sealed, deemed too dangerous for the curious. But you’ve often wondered where they now lead, how many others link the little caverns of the city.

You sometimes open the old files, read their voices, and talk to friends who remember the way it once was in such a wonderful poetry of class, manners, and violence. But to see it, to see that clarity of light on the old brick of Ybor City where shotguns rang out to settle the feud after Santo Trafficante Sr. died, or feel the excitement of driving to the next murder scene or bank heist or two-bit shoot-out, you must strip away everything you see today.

You must walk to the corner of Franklin and Polk and not look back, for fear that you will only see the soulless glass-and-steel place Tampa has become, but look at that dead corner of five-and-dimes, the Woolworth’s and the Kress’s, and over their roofs from the old Floridan Hotel, where we all used to drink at its big bar called the Sapphire Room and where Eleanor broke your heart at least twice.

You must ignore the black vultures roosting on the mammoth sign spelling out the hotel’s name in metal as wind beats into broken windows and derelicts sleep on the floor of the grand old lobby. You have to drive down to Seventh Avenue and remember how it used to be with the Sicilians and Cubans going down to the Ritz Theatre and shopping for twenty-dollar suits and guayaberas at Max Argintar’s or the way that yellow rice and black beans would smell on the heavy wooden tables of Las Novedades where Teddy Roosevelt had once ridden a horse through the kitchen.

Or see the shadows in the old Italian Club where the killings were discussed and where the Shabby Attorney came with his fiery words of revolution.

It’s all cigar smoke and light and shadows and ticking Hamilton watches and the smell of the salty bay blowing over forgotten crime scenes.

The story of the Shabby Lawyer, the Girl who was protected by the Giant, the hidden tunnels, all begin with Charlie Wall and that night in April 1955.

And that’s where you must begin, too. Because the tunnels are open, and the cigar factories are no longer burned-out shells with plywood windows but working brick warehouses. Ybor City is filled with shoppers in straw hats and two-tone shoes, and the cops walk the Franklin Street beat from Maas Brothers department store up to Skid Row and the drunks and derelicts and burlesque shows.

The

Times

newsroom is open and clicking with the sound of a dozen Royals and L.C. Smiths, and you are only minutes away from deadline and meeting Eleanor down at the Stable Room at the Thomas Jefferson Hotel to talk about Nietzsche, poor Charlie Parker, or the Tampa Smokers’ new pitcher, and thinking of her fifty years later still makes you hurt inside.

Times

newsroom is open and clicking with the sound of a dozen Royals and L.C. Smiths, and you are only minutes away from deadline and meeting Eleanor down at the Stable Room at the Thomas Jefferson Hotel to talk about Nietzsche, poor Charlie Parker, or the Tampa Smokers’ new pitcher, and thinking of her fifty years later still makes you hurt inside.

It’s 1955 again. You are twenty-six years old and ambitious, and the tunnels are lit. And waiting.

I

THE DEVIL’S OWN

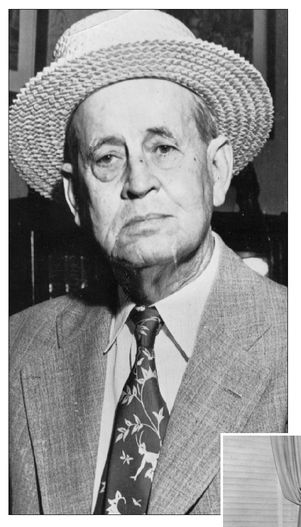

Charlie Wall

The crime scene

ONE

Monday, April 18, 1955CHARLIE WALL LAID OUT the crisp white suit on his bed and wiped off his wingtips with a hand towel he’d used to dry his face after shaving with a straight razor. It was early evening and dark in the house, but the setting sun broke through the curtains and blinds and gave it all such a nice glow. He combed his hair with a silver brush, watching his eyes in the circular mirror above his dresser, and removed his bathrobe and slippers and dressed in a newly laundered shirt and pants and slipped into his coat and shoes. He checked his face for an even shave, splashed a bit of Old Spice across his sagging jowls, and decided that for a man fast approaching seventy-five he wasn’t a bad-looking character.

His last touch before closing the front door to his big, sprawling bungalow in Ybor City was to slip a straw boater on his head and check its angle in the window’s reflection.

The metal gate closed behind him with a

click,

and he opened the door to the waiting cab.

click,

and he opened the door to the waiting cab.

Charlie Wall, retired gangster, was ready to hold court.

Monday night was a slow night in downtown Tampa, and Charlie met the usual crew at The Turf.

The Turf was a solid bar at the foot of the old Knight and Wall dry goods warehouse. He talked local politics with adman Jack Lacey and women with Frank Cooper, who’d closed up shop at Knight and Wall. And Charlie opened up his money clip to hand the bartender, Babe Antuono, a twenty for the drinks. But Jack told him to put his money away, because Jack Lacey was a class guy and remembered that old Charlie had paid for the last round on Friday.

The plate-glass windows looked out onto Jackson Avenue, and it had grown dark during the conversation and dirty jokes, and pretty soon Frank had to meet his wife for a show and then Jack had to get home for dinner. The paddles of ceiling fans broke apart the smoke left from the men’s cigarettes.

Pretty soon Charlie Wall was alone. He had another Canadian Club highball, his fourth in an hour, and talked boxing with Babe. Babe used to run a tobacco stand across the street, and they talked a little about Ybor City and some of the characters they all knew.

“How’s Scarface Johnny?” Babe asked.

“Don’t ask,” Charlie said. He sipped some more drink.

“Baby Joe?”

“He’s fine.”

Soon four young women walked into the bar with a giggle, their eyes all made up with mascara and false lashes, and they sat across from Charlie at the bar. One dropped a dime into the jukebox and played Hank Williams singing “Kaw-Liga,” and the women chatted and giggled and squealed. Babe beat out the song’s rhythm on the wooden bar.

Charlie bought the women a round and toasted them with an empty highball that was soon refilled. They came over and talked to him for a while and they liked him. They liked the funny old man in the white suit with the white straw hat and they liked his Cracker drawl and the harmless way he flirted and stared at their chests. And they stayed for a while, listening to him talk about the places to find the juiciest steaks.

One of the girls tried on his hat.

They laughed but soon disappeared.

How were they to know?

“You used to have a few of them,” Babe said, cleaning off a glass with a towel and checking it against the light. Almost reading his mind. “I bet you couldn’t keep them straight.”

“I had a few.”

“When did you get started? You know, in the business?”

“Before the war.”

“The first big one,” Babe said. “Wow.”

“No,” Charlie said. “The war with Spain. I took bets for soldiers who’d come down with Teddy Roosevelt. I ran crap games and took twenty-five percent off the whores I’d sneak into camp.”

Other books

Bite the Moon by Diane Fanning

Lord of the Shadows by Darren Shan

Bartimaeus: The Golem’s Eye by Jonathan Stroud

Singapore Fling by Rhian Cahill

Darkthaw by Kate A. Boorman

Pirates of the Caribbean 02 The Siren Song by Rob Kidd

Broken Hart (The Hart Family) by Ella Fox

The Anomaly by J.A. Cooper

El último deseo by Andrzej Sapkowski

Trapped by Gardner, James Alan