"Who Could That Be at This Hour?" (All the Wrong Questions) (8 page)

Read "Who Could That Be at This Hour?" (All the Wrong Questions) Online

Authors: Lemony Snicket

Tags: #Juvenile Fiction / Juvenile Fiction - Social Issues - Adolescence, #Juvenile Fiction / Mysteries & Detective Stories, #Juvenile Fiction / Family / General

Moxie finished her cranberry juice. “So?”

“Do you know,” I asked her, “that

orecchiette

is Italian for ‘little ears’? I know it’s just the shape of the noodle, but some people don’t like the idea of eating a big bowl of—”

“That’s not what I mean, and you know it, Snicket. Why does someone want a statue everyone else has forgotten?”

“I wouldn’t know,” I said.

She reached over and opened up her typewriter to add a few sentences to her summary. “There’s something going on that we can’t see.”

“That’s usually the case,” I said. “The map is not the territory.”

“What does that mean?”

“It’s an adult expression for the muddle we’re in.”

“Adults never tell children anything.”

“Children never tell adults anything either,” I said. “The children of this world and the adults of this world are in entirely separate boats and only drift near each other when we need a ride from someone or when someone needs us to wash our hands.”

Moxie smiled at this and began to type. I meant to stack the dirty plates in the sink, but I liked staying at the table and watching her at work. “Do you like that?” I asked her. “Typing up what happens in the world?”

“Yes, I do,” Moxie said. “Do you like what you do, Lemony Snicket?”

I stared out the kitchen’s lone window. The moon had risen like a wide eye. “I do what I do,” I said, “in order to do something else.”

I was certain she would ask more questions, but we were interrupted by the lonely and familiar clanging of the bell. Moxie frowned at a clock with a face like that of an angry sea

horse. “There’s not usually an alarm at this hour,” she said.

“When does it usually ring?”

“It depends. For a while it seemed like it was ringing less and less frequently, but lately it’s started up again like gangbusters.”

“Who rings it, anyway?”

Moxie stood on her chair to reach a high shelf. “The bell tower is over on Offshore Island, where there used to be a fancy boarding school that everyone called ‘top drawer.’”

“I always thought that was a curious expression,” I said. “After all, the most interesting things are usually in the bottom drawer.”

Moxie smiled in agreement. “Back then the bell was rung by the student valedictorian, but Wade Academy closed some time ago. Now the bell is rung by someone from the Coast Guard, I think, or maybe it’s the Octopus Council.” She took two masks down from the shelf and

handed one to me. “Don’t worry, Snicket. We have plenty of spares. You won’t get salt lung.”

“Salt lung?”

“That’s what the bell is for,” she explained. “When the wind rises, it carries salt deposits left behind on the floor of the sea, which can be dangerous to breathe. The masks filter the salt out of the air.”

“I heard the masks were for water pressure,” I said.

Moxie frowned into her mask. “Where did you hear that?”

“From S. Theodora Markson,” I said. “Where did you hear about salt lung?”

“Some society put out a pamphlet,” Moxie said, gesturing to the stuffed drawer. We put on our masks and faced each other. “I don’t much like talking with these on,” she said. “Shall we read until we hear the all-clear?”

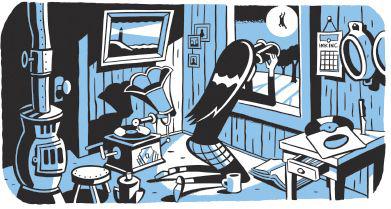

I gave her a masked nod of agreement, and

she led me into a small room where the walls were stuffed with bookshelves, and a large floor lamp stood in the middle. A big bulb cast a bright circle of light from under a shade decorated with a creature I was getting tired of looking at. There were two large chairs to sit in, one piled with more typewritten pages and the other surrounded by thick, sad-looking books on the decline of the newspaper industry and how to raise a daughter all by yourself. On the carpet I could see marks on the floor where a third chair had been dragged away. Moxie sat in her chair and put her typewritten notes in her lap and told me to help myself. I found a book that did nothing to relax my nerves. The story took place in some big woods where a little house was home to a medium-sized family who liked to make things. First they made maple syrup. Then they made butter. Then they made cheese, and I shut the book. It was more

interesting to think about stealing a statue and making my way down a hill on a hawser high above the ground. “Interesting” is a word which here means that it made me nervous. I walked over to the window and tried to see how far it was from the lighthouse to the Sallis mansion, but the sun was long down, and outside was as black as the Bombinating Beast itself. It wasn’t much of a view, but I stared at it for quite some time. After a while the bell clanged the all-clear from the island tower, and I took off my mask and realized Moxie had fallen asleep behind hers. I slipped her mask off and found a blanket to put on her and went back to my staring. I thought maybe if I stared hard enough, I could see the lights of the city I had left so very far behind. This was nonsense, of course, but there’s nothing wrong with occasionally staring out the window and thinking nonsense, as long as the nonsense is yours.

Before long the clock was bombinating twelve times, but it was a quiet buzzing, so I heard Theodora’s roadster outside without a problem. Moxie didn’t stir, so I shook her shoulder slightly until her eyes flickered open.

“Is it time?” she said.

“It’s time,” I said, “but you would do me a great favor if you went to bed.”

“And miss all the fun?” she said. “Not on your life, Lemony Snicket.”

“You said yourself there’s something going on we can’t see,” I said. “It might be something dangerous.”

“In any case, it’s something interesting,” Moxie said, “and I’m going to find out all about it.”

“Moxie, we can’t burgle you if you’re standing around watching. At least hide yourself.”

She stood up. “Where?”

“You grew up in this lighthouse,” I said. “You know all the best hiding places.”

She nodded, packed up her typewriter, and walked out of the room. I put out the lights and then opened the front door. The roadster was parked in front of the lighthouse, but I couldn’t see Theodora. I walked a few steps out and called her name.

My chaperone emerged from the night, crouching along the ground as she made her way. She had changed her clothes and was wearing black pants and a black turtleneck sweater, with black slippers on her feet and a small black mask over her eyes. Her immense hair was tied up in a complication of black ribbons, and her face was dusted with something black to help her blend in. I once saw a cat run up a chimney and then immediately come back down covered in soot to ruin the living room furniture, and I noticed several striking similarities between this memory and the woman who was moving stealthily toward me.

“There are burglary clothes in your suitcase,”

she hissed. “Why aren’t you wearing them? We don’t want to attract attention.”

“Perhaps you should have parked someplace else,” I said, pointing to the roadster.

“Keep your voice down,” she said. “We’ll wake people up.”

One way to keep one’s voice down is to stop talking altogether, which is also one way not to argue with somebody. I beckoned to Theodora, and we slipped into the house and made our way up the spiral staircase, Theodora pressing herself against the walls of the lighthouse and swiveling her head this way and that, and me walking like a normal person. I led her into the newsroom, removed the sheet, and pointed to the statue of the Bombinating Beast. She gestured to me that I should be the one to take it. I gestured back that she was the chaperone and the leader of this caper. She gestured to me that I shouldn’t argue with her. I gestured to her that I was the one who had gotten us into the house in the first

place. She gestured to me that my predecessor knew that the apprentice should never argue with the chaperone or complain and that I might model my own behavior after his. I gestured to her asking what the

S

stood for in her name, and she replied with a very rude gesture, and I grabbed the statue and tucked it into my vest. It was lighter than I thought it would be, and I felt less like a burglar and more like someone who was simply carrying an object from one place to another.

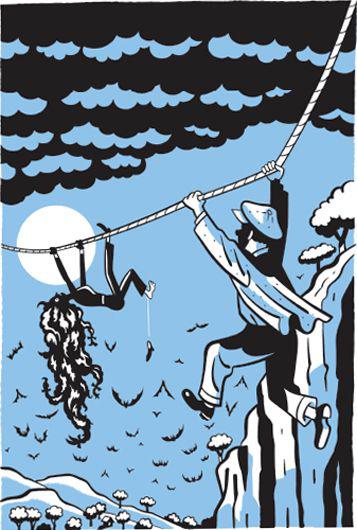

I opened the window and reached a hand down into the darkness until I could feel the hawser rough and cold against my palm. This made me feel more like a burglar. I held it steady for Theodora to grab with both hands, and then I lowered myself after her. I couldn’t reach to shut the window, but I figured Moxie would do it once she came out of hiding. I wondered if she could see us now as we began to climb, hand over hand, along the hawser toward the Sallis

mansion at the bottom of the hill. We must have been strange shadows against the round, white moon. The rustling of the Clusterous Forest grew softer as we got farther and farther away, and the still night air filled my throat. I was not as high up as I thought I would be, and the hawser stayed steady as we continued our descent. In the moonlight I could see the trees below us, the thin branches all folded together like laced-up shoes, and the leaves looking lonely and uncomfortable. I could see the small white cottage, with something glinting in one of its windows—some small object that was reflecting the light of the moon. What I did not see was a candle, as Theodora had told me there would be, to signal that all was clear.

“Snicket,” Theodora said, “this would be a good time to ask me a question.”

“Why?” I tried.

“Because I am somewhat afraid of heights,” she answered, “and answering an apprentice’s

questions would be a good way to distract me.”

“OK,” I said, and thought for a moment. “Do you think this is the way the statue was stolen?”

“Absolutely,” Theodora said. “The Mallahans must have climbed down the hawser, grabbed the statue, and gone back out the way they came.”

“I thought you said they came in from the parlor,” I said, “by sawing a hole in the ceiling and letting gravity do the rest.”

“That was an early theory of mine, yes,” Theodora said, “but at least I was half-right: Gravity is involved. This would be a much harder climb if we were going up this hill instead of down.”

What Theodora said was true—it would have been much harder to move hand over hand up the cable—but she had also said the thieves had gone back out the way they had come. Arguing with my chaperone, however, probably would not have distracted her from her condition. There was a word for a fear of heights, I knew, but I couldn’t think

of it. Something-phobia. “How do you think the thieves got into the Sallis mansion?” I asked.

“Through one of the windows of the library, of course,” Theodora said. “The hawser goes right there.”

“Mrs. Sallis said the windows are always latched,” I reminded her.

“Well, they’re not latched now,” Theodora said. “Look. The butler is giving us the signal that all is clear.”

Sure enough, I could see the faint shape of the open window, right where the hawser ended, and in the middle of that shape was a faint light. Hydrophobia? I thought. No, Snicket. That’s the fear of water. The light did not look like a candle, as it was not flickering, and it was bright red in color. A bright red light reminded me of something that I also could not quite remember. Agoraphobia, I thought. No, Snicket. That’s the fear of wide-open spaces.

“We’re almost there,” Theodora said. “In a minute the Bombinating Beast will be returned to its rightful owner, and this case will be closed.”

I did not answer, because it had come to me all at once, like a light turning on. It was the red flashlight the Officers Mitchum had on top of their car. And “acrophobia” is the word for a fear of heights. I let go of the hawser and fell straight down into the trees.

It was pitch-black everywhere around me,

and I felt as if I had fallen into the path of an enormous shadow. I had learned how to do it, in what you would probably call an exercise class, but that doesn’t mean it wasn’t difficult or frightening to fall that way. It was difficult and frightening. The fall was quick and dark, and I landed in the tree on my back, with many twigs and leaves poking at me in annoyance. Still I felt it. Then I relaxed, as I had been trained

to do, and lay out on the top of the tree, letting it support my weight, but still I felt the enormous shadow cast upon me. It was not the shadow of the hawser, or of any of the other trees nearby. It was the face that appeared next to me, the face of a girl about my age. I could also see her hands, clutching the top of a ladder she must have leaned against the tree. Somehow I knew, as she blinked at me on top of the ladder, that the girl in question had already begun to cast an enormous shadow across my life and times.