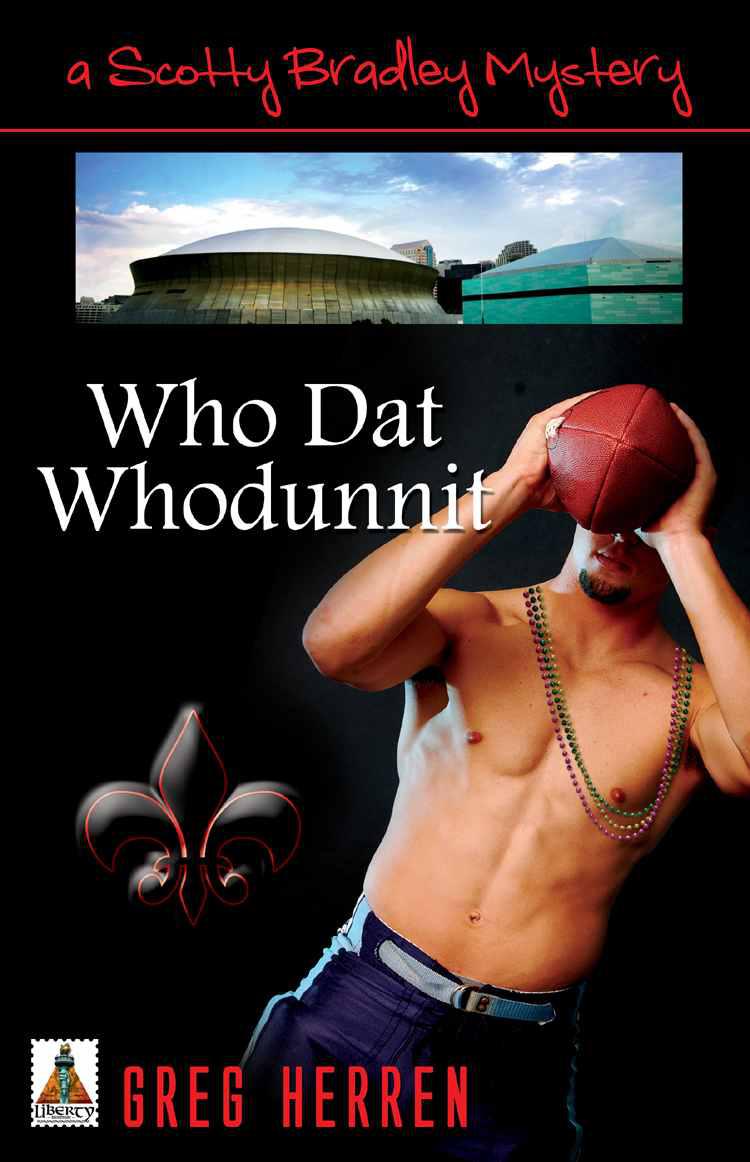

Who Dat Whodunnit

Authors: Greg Herren

The Saints’ victory in the Super Bowl just prior to the start of Carnival season has everyone in New Orleans floating on Cloud Nine. But for Scotty Bradley, Carnival looks like it’s going to be grim yet again when his estranged cousin Jared—who plays for the Saints—becomes the number one suspect in the murder of his girlfriend, dethroned former Miss Louisiana Tara Bourgeouis. Scotty’s not entirely convinced his cousin isn’t the killer, but when he starts digging around into the homophobic beauty queen’s sordid life, he finds that any number of people wanted her dead. With the help of his friends and family, he plunges deeper and deeper into Tara’s tawdry world of sex tapes, fundamentalist fascists, and mind-boggling secrets—secrets some are willing to kill to keep!

Who Dat Whodunnit

Brought to you by

eBooks from Bold Strokes Books, Inc.

http://www.boldstrokesbooks.com

eBooks are not transferable. They cannot be sold, shared or given away as it is an infringement on the copyright of this work.

Please respect the rights of the author and do not file share.

Who Dat Whodunnit

© 2011 By Greg Herren. All Rights Reserved.

ISBN 13: 978-1-60282-225-2

This Electronic Book is published by

Bold Strokes Books, Inc.

P.O. Box 249

Valley Falls, New York 12185

First Edition: May 2011

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the author's imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

This book, or parts thereof, may not be reproduced in any form without permission.

Credits

Editor: Stacia Seaman

Production Design: Stacia Seaman

Cover Design By Sheri ([email protected])

The Scott Bradley Adventures

Bourbon Street Blues

Jackson Square Jazz

Mardi Gras Mambo

Vieux Carré Voodoo

Who Dat Whodunnit

The Chanse MacLeod Mysteries

Murder in the Rue Dauphine

Murder in the Rue St. Ann

Murder in the Rue Chartres

Murder in the Rue Ursulines

Murder in the Garden District

Sleeping Angel

Love, Bourbon Street: Reflections on New Orleans (edited with Paul J. Willis)

This is for the SUPER BOWL XLIV CHAMPION

NEW ORLEANS SAINTS

Bless you, boys, and thank you.

“Ignorance—of mortality—is a comfort. A man don’t have the comfort, he’s the only living thing that conceives of death, that knows what it is.”

—Tennessee Williams,

Cat on a Hot Tin Roof

“What kind of Fascist state would deny a gay man a bridal registry?”

—Margaret Cho

“This stadium used to have holes in it, and it used to be wet. Well, it isn’t wet anymore. This is for the city of New Orleans.”

—Saints Coach Sean Payton,

accepting the NFC Championship Trophy

It was the best of times.

It was the craziest of times.

Well, what it

really

had to be

was the end times, which was the only logical explanation for what was going on in the city of New Orleans.

Pigs grew wings and nested in the branches of the beautiful live oaks everywhere in the city. Some thought the pilot light in hell had gone out, so that icicles hung from the noses of shivering demons in the realm of the dark lord. Others starting watching the horizon for the arrival of the Four Horsemen, for surely the Apocalypse must be coming. Surely the earth was tilting in its axis. Maybe aliens would land in Audubon Park, or the Mississippi River would start flowing backward.

Anything and everything was possible, because the Saints were

winning.

GEAUX SAINTS!

People who don’t live in the South don’t really understand how important football is down here. Football is more than a religion in the Deep South. I’m not sure why it is—my mom claims it’s because the South lost the Civil War—but it’s true. On Saturdays, when the colleges play their games, the entire region comes to a complete halt. People live and die by their teams—whether it’s LSU, Ole Miss, Alabama, Auburn, Florida, Georgia or Tennessee—and how they fare on Saturday. I myself grew up cheering for the LSU Tigers—even though attending Vanderbilt was a family tradition on my mother’s side. Whenever Papa Fontenot gives me crap for dropping (well, flunking is probably a more accurate word) out after my sophomore year, I give him a withering look and reply, “Maybe I’d have done better at LSU.”

That always shuts him up.

But as much as we love football, here in New Orleans we’ve known nothing but shame for decades. Tulane, the only major university within the city limits, might as well not even have fielded a team, they were so hopeless. And the Saints, our NFL team, were probably the most hopeless case in the entire league. For forty-two years, the Saints (sometimes called the Aints) failed spectacularly. It took them over twenty years to post their first winning season. Yet somehow, we loved them. No matter how bad they were—and they were pretty bad most of the time—we kept on loving them and cheering for them. They were ours, and well, if they were losers, they were still OUR losers. The Saints were like that crazy uncle every family seems to have, you know what I mean? You don’t stop loving him because he’s a screw-up and a failure. You just keep loving him and hoping for the best, thinking

maybe someday he’ll get it together.

Even though he never seems to succeed—and sometimes, many times, he shoots himself in the foot.

But this year, things were

different.

The fever spread through the city faster than bubonic plague. Each week, the excitement built as our sad-sack always-an-also-ran NFL team mowed down every team they faced. Every Sunday, at game time, the streets were as deserted and empty as they’d been those months after the floodwaters from the levee failures receded. For those few hours, New Orleans turned into a ghost town, eerily silent until a roar would erupt from the nearest bar—a roar that meant the Saints had scored.

By the time the team was 4–0, people were saying this could be the year we went to the Super Bowl. No one talked about

winning

the Super Bowl; just making it there was more than enough for us long-suffering Saints fans. As hopeful as we were, there was always that thought in the back of our minds—

Is this a fluke? Will the clock strike midnight and turn the Saints back into field mice from champions?

But somehow, week after week, they kept winning.

People were talking about destiny.

And the city turned black and gold.

Even those people who didn’t care for football were hanging Saints flags on their houses, writing FINISH STRONG on their car windows in grease pencil, and wearing jerseys on game days. Everywhere you turned on Sundays, all you could see were locals in Saints jerseys. Anything with a fleur-de-lis, the words “Who Dat,” or the Saints logo on it just flew off the shelves. Even the gay bars turned off their traditional music videos on Sundays and played the games for crowds of jersey-wearing gay men, offering drink specials every time the Saints scored. One bar started calling vodka-and-cranberry a “Drew Brees.”

Priests took to performing Sunday mass in Saints jerseys, and closing with a prayer for a Saints victory.

The fever was everywhere. It was bigger than Mardi Gras.

It was almost as though it was ordained somehow.

Some of the wins were not only improbable, they were impossible. Down by seven points against the Redskins, less than three minutes left in the game with the Redskins getting ready to kick a field goal to clinch the game—they somehow found a way to win. Down twenty-one points to the Miami Dolphins, they wound up winning.

Week after week, somehow the Saints just kept winning.

And eventually, the Minnesota Vikings came to the Superdome with the NFC Championship on the line, and a trip to the Super Bowl—the Promised Land Saints fans never once believed we’d ever see after wandering forty-two long years in the desert.

My name is Milton Scott Bradley, but you can just call me Scotty. I am a born and bred New Orleanian, and I bleed black and gold. I live in the French Quarter with my two boyfriends, Frank Sobieski and Colin Cioni. Yes, I have two boyfriends—but Colin’s work takes him away most of the time. Frank and I have a private detective business—Bradley & Sobieski.

And that Sunday night, my parents decided to invite people over to watch the Saints play (for only the second time in their history) for a chance to go to the Super Bowl.

And it came down to a field goal—

in overtime.

An entire city—no, an entire state—held its breath as a twenty-three-year-old kid who’d missed a game-winning kick a few weeks earlier trotted out onto the field with a chance to go down in New Orleans history as either a great hero or as the goat.

The ball was snapped.

All I could do was whisper “oh my God” as I watched him swing his leg. My eyes filled with tears of shock and joy as I watched the ball go up in the air, travel forty yards spinning end over end, and cleanly split the uprights.

And the entire city of New Orleans spontaneously erupted with joy.

By that time, I was emotionally exhausted and drained. With about five minutes left in the game, I just went completely numb. I’ve never experienced anything even remotely like that during a football game; it was weird, like I’d blown a circuit in my brain. I had alternated between joy and disappointment throughout the entire game, but as the game wound down I was numb from head to toe and felt nothing but an unearthly calm that frankly had me worried I’d had a mini-stroke or something. When the Saints intercepted legendary Vikings quarterback Brett Favre with nineteen seconds left in the game, I could hear the cheers roaring and echoing from every direction outside. In my parents’ living room, people were screaming and cheering, jumping up and down—but I just sat there on the couch, unable to believe what I was seeing, to process what had just happened.