Who Made Stevie Crye? (14 page)

Read Who Made Stevie Crye? Online

Authors: Michael Bishop

Tags: #Fiction, #science fiction, #General

XXVIII

“

I fell apart down deep,” Crye said

, a dead hand on his wife’s forehead. “If I appeared to give up, Stevie, it was only because it was time for me to pay.” Crye’s face bore an expression of grisly melancholy and compassion, but his hand did not cease pressing his wife ever deeper into the Clinac 18’s couch.

“Pay for what?” asked Mrs. Crye, her eyes wide with half-repressed terror. “What must you pay at this late date, Ted?”

“The dosimetrist’s bill.”

“The Kensingtons took care of that, Ted. The life-insurance policy you bought was inadequate to our needs, and you never even bothered to look into the hospitalization plan they recommended. It’s a shameful fact that—”

“Stevie,” murmured Theodore Martin Crye, Sr.

“— if not for the fund-raising efforts of Dr. Sam and Dr. Elsa, the kids and I would still be up to our elbows in debt to the cancer clinic. The people you

don’t

have to pay, Ted, include the dosimetrist, the radiologists, and the nuclear-medicine technicians. Besides, what sort of debt would turn a self-sufficient man like you into a shambling defeatist?”

“The debt of mortality,” Crye said.

“The debt of guilt,” said Seaton Benecke, clinic dosimetrist.

“But you owe these people nothing,” Mrs. Crye said. “I’ve explained that to you. You certainly don’t owe Seaton a dime. He’s a typewriter repairman, Ted, not a radiation dosimetrist. I can’t even imagine what he’s doing here.”

“He’s come to collect the payment I owe him.”

“What payment?”

“He wants to enjoy your person, Stevie.”

Mrs. Crye studied the pale noncommittal face of the typewriter repairman. She looked at her husband, a resurrected corpse whose features slid about in the same discouraging way they did in her memory. His breath was odorless, antiseptic. His clammy hands kept pressing her into the treatment couch. He would not relent. Without returning Mrs. Crye’s gaze, Seaton Benecke moved to the foot of the couch and began unbuttoning his lab coat.

“I’m your wife,” Mrs. Crye told her husband’s corpse. “I’m not a piece of equipment you can loan out or give away to repay your debts. We’re not Eskimos, Ted. This isn’t the Arctic Circle.”

“But it’s cold in here,” Crye said.

Seaton Benecke permitted his lab coat to fall to the icy floor of the treatment room. He began unbuttoning his shirt.

“Ted, you can’t be serious. You’re out of your mind. You don’t help a creep like Benecke rape your own wife.”

“It’s all right,” Crye said. “I’m dead.”

“It’s all right,” Benecke added. “I’m an organ-grinder.” In unbuttoning his shirt, he had revealed a swatch of thick white fur from his throat to his navel. His fingers moved deftly to his belt buckle. “I mean I’m an organ-grinder’s monkey,” he corrected himself.

Mrs. Crye closed her eyes, twisted in the corpse’s grasp, and screamed. Her screams were high-pitched, piercing, and many, one coming after another like the notes of an avant-garde flute sonata.

“Your screams will avail you nothing, my beauty,” the corpse said, slamming her back into place, and his voice did not sound at all like Theodore Martin Crye, Sr.’s. It sounded like that belonging to the insanely serene computer in the film

2001: A Space Odyssey

.

“Ted!” cried the distraught woman. “Ted, don’t!” She screamed again.

Meanwhile, a creature like a huge white-throated capuchin crept up the length of the treatment couch, lifting the hem of her skirt as it neared her face. Mrs. Crye’s head rolled from side to side, but she could not escape the restraints of her traitorous husband or the knee pressure of the monkey-man astride her.

“I’m just giving it a special twist here,” Benecke said, stroking her breasts with a furry paw. “I can go in as deep as fifteen centimeters before ‘exploding’ through the life-bearing dark. That’s what I really like.”

“I fell apart down deep,” Crye said, a dead hand on his wife’s forehead. “If I appeared to give up, Stevie, it was only because

Mrs. Crye could no longer hear her own screams. When she opened her eyes, she found that she was alone with Crye’s corpse in a basement detection-and-diagnosis rooms. Her dead husband was explaining to her the purpose and operation of a machine connected to a small viewing console.

“This unit allows the radiologist to watch a patient’s gastrointestinal tract as it fills with barium sulfate,” he said.

“I went through all this when you went through it,” Mrs. Crye said. “I went through it all again to write an article on the clinic for the

Ledger

. Why are you subjecting me to the experience yet again?”

“Barium sulfate is simply a contrast medium,” Crye said. “It’s used to show up any abnormalities in the GI tract. The examiner views the diagnostic process almost as if watching a movie.”

“I wrote those words last week, Ted. I took them down from the lips of a clinic radiologist, and I put them into my story.”

“This machine works on the fluoroscopic principle, but in other parts of the clinic are a thermographic unit, which detects tumors through a heat-sensing process, and an ultrasonic device which employs sound waves to locate and identify cancerous growths. Many other diagnostic aids are available to us here. Of course you’ve already seen the Clinac 4 and the Clinac 18 in the treatment areas.”

“None of these marvels is worth anything if you will yourself to die,” Mrs. Crye said. “If you surrender to the

idea

of cancer.”

Crye turned to face his wife. Out of deference to her wifely sensibilities he was wearing handsome glass prostheses in his empty eye sockets. His complexion, however, still had a sickly cast. “I want a divorce,” he said.

“You’re dead,” Mrs. Crye reminded him. “You don’t need a divorce. I’m a widow. I can remarry without a divorce decree, and you can —”

“— rot in hell.”

Mrs. Crye lowered her face into her hands. “Please, Ted, don’t.” She immediately raised her head again and put her hands on her knees. “Hell is a mental state. I’m the one who’s in it. You’re too good—you

were

too good—a man to end up in hell.”

“Even good men can have hellish mental states, Stevie. I want a divorce.”

“How does a living widow give her dead husband a divorce?”

“She lets go,” Crye said. “She stops bringing him into the clinic for fluoroscopic examinations. She stops pouring barium sulfate into him. She stops trying to read his goddamn entrails on this little television screen.”

“Ted, I never —”

“You’re not a licensed haruspex, Stevie. Becoming a licensed dosimetrist, radiologist, or haruspex requires a lot of hard work. If you won’t give me a divorce, I may have to file a malpractice suit.”

“But why do you want a divorce? I loved you. I’ve acted as I have because I loved . . . because I love you.”

“There’s another woman,” Crye said.

“No, Ted. You’re lying. You’re casting about for excuses.”

“There’s another woman, Stevie. I’m going to go with her. I want a divorce. Let go of me so that I can go with her.”

Mrs. Crye crossed the tiny room and gripped her dead husband’s wrists.

The flesh sloughed away in her hands. “You can hold me, Ted, but I can’t hold you. If it makes you feel better, call my inability to hold you a divorce.”

She dropped the hose-like lengths of clammy flesh to the floor. “But don’t try to tell me there’s another woman. I refuse to believe it.”

Gingerly, Crye pushed past his wife, visited all the diagnostic-rooms along the corridor, and returned to the fluoroscopic unit carrying tomograms, radioimmunoassays, sonographic readouts, and a handful of X-rays. He pushed a mobile mammographic unit before him, maneuvered it right up to Mrs. Crye, and scattered the other items across the top of an examination table next to her abandoned chair. His skeletal fingers lifted the results of each diagnostic test to within fifteen centimeters of his wife’s nose.

“Evidence of the other woman,” Crye said. “Nuclear body scans, sonograms of the internal organs, thermograms taken after she’d spent ten or fifteen minutes cooling off from our last encounter, not to mention several high-speed, low-dosage X-rays of her breasts. These last are especially impressive. Put them all together they spell paramour. . . .”

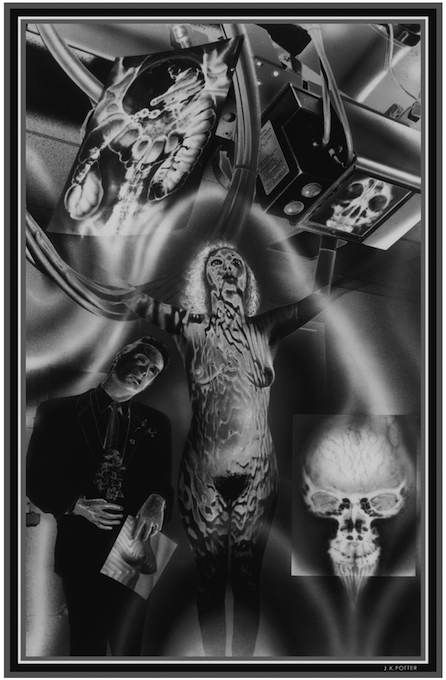

The lights in the clinic basement went out, almost as if a generator had failed, and sitting behind the mammographic unit that Crye had just wheeled in was the three-dimensional image of a strange woman. Her insides—from brain to toe bones—were visible as blinding splotches of green, blue, magenta, and yellow. She stared at Mrs. Crye from her Technicolor death’s-head while the horrified recipient of this stare raised an arm and tried to warm the naked body of the corpse in her bed. After fetching the electric blanket’s control from the bottom dresser drawer, she clocked it to its highest setting. Then she climbed into the bed beside her dead husband and snuggled against him to add her own warmth to that imparted by the blanket. Immobile and helpless, he stared with empty eye sockets at the ceiling. His breath was odorless, antiseptic. To die a second time, he would have to improve markedly.

“Care for some orange juice?” Mrs. Crye asked. “A hot toddy with honey and lemon?”

“It would seep right through me and ruin the mattress pad. Citric acid has that unfortunate effect on most sorts of bed linen.”

“I don’t care. I want you better. This has been a demoralizing two years.”

“You should remarry.”

“ ‘A woman without a man is like a fish without a bicycle.’ ”

Crye laughed. “ ‘Don’t switch corpses in midscream,’ eh?”

“Something like that. That’s a ghoulish way to put it, though. I was trying to point out—obliquely—that I married you because I loved you, not because I was single-mindedly looking for a man.”

“No woman is single-minded when she looks for a man.”

“Stop it, Ted. I’m just saying that remarriage isn’t the answer.”

“You should date that Benecke boy, Stevie.”

Mrs. Crye moved away from her husband. “That’s not amusing. I’d seduce my own son before I dated Benecke.”

“What’s the matter with him?”

“He’s an inarticulate Svengali. He once convinced you to help him rape me. And his table manners are atrocious.”

“He probably uses his salad fork for the entrée.”

“At lunch one afternoon he let his pet monkey suck blood from a wound in his finger. Dessert, he called it. Teddy and Marella were there.”

“He’s young yet, Stevie. What else?”

“What do you want me to give you, Ted? His teachers’ conduct reports? A list of his traffic citations? His last criminal indictment? He’s not my type!”

“He’s a piker, and you’re elite.”

“Ha, ha,” Mrs. Crye said. She turned toward her husband again. “Just tell me what you thought you had to pay for, Ted. What so discouraged you that you turned your back on all the marvelous aids, all the helpful people, at the cancer clinic in Ladysmith?”

“It was time for me to die.”

“I don’t get that!” Mrs. Crye protested, hitting the bed with her fist.

Her dead husband summoned a burst of residual

élan vital

and threw back the covers. Like Karloff in one of James Whale’s

Frankenstein

movies, he rose from the bed . . . dressed in the suit in which he had been buried. It wanted dry-cleaning and pressing. He strode to the mirror and clumsily tried to straighten the knot in his tie. The room’s darkness proved no deterrent to his efforts, for he could not have seen his bony fingers even with the lights on.

“And I don’t deserve to share the same bed with you,” Crye said huskily. “I robbed you of any incentive to develop your own talents. I bought you that fancy-ass Exceleriter, but didn’t give you time to use it and thus decided to die.”

“So I could spend my life in front of a typewriter?”

“Matriculating in the graduate school of experience, developing your talents, confronting adversity.”

“You never talked like that when you were alive.”

“Only toward the last did I even begin to think like that, Stevie. I had to die so that you could step out from my oppressive shadow.”

“Into the arms of a shade?”

Crye swung about to face the bed, but one foot did not turn with him. His diamond tie tack glinted in the green-yellow sheen from the arc lamp outside. The knot of his tie was a thumb’s length off-center. A button fell from his jacket and rolled toward the cedar chest. He was falling apart not only inside but out-.

“What I’m saying’s meant nobly. It’s heartfelt, too. It’s an altogether heartfelt lie. . . . Kiss me, Stevie. Show me you believe me by giving me a kiss.”

Mrs. Crye went to her husband and gave him a kiss. His lips tasted like oyster dip on dry crackers. When she pulled away, though, she was staring into the face of an organ-grinder monkey whose bones shone green, blue, magenta, and yellow in the second-story gloom. The ascot at his throat was white fur. When he opened his mouth, the phosphorescent keyboard of his teeth began to clatter and chime. Mrs. Crye opened her mouth too. The sound that issued forth reminded her of