Whom the Gods Love

To Steven Come, Reed Drews, Jay Harris, and Peter Mowschenson, without whom there would have been no Julian Kestrel

AUTHOR’S NOTE

The characters in this novel are fictitious. Streets, villages, and other locales mentioned by name are authentic, with the exception of Cygnet’s Court, Haythorpe and Sons, and the Jolly Filly. Readers who know Hampstead may perceive that Sir Malcolm’s house in the Grove (since renamed Hampstead Grove) is based, very loosely, on Fenton House. Serle’s Court, where Quentin Clare has his chambers, is now New Square, and a garden has displaced the gravel, fountain, and clock.

I would like to thank Dana Young for giving me the benefit of her expertise on horses and riding. I would also like to thank the Honourable Society of Lincoln’s Inn—in particular the Chief Porter, Leslie Murrell—for their kind assistance with my research. Finally, I am grateful for the help and encouragement of the following people: Julie Carey, Cynthia Clarke, Mark Levine, Louis Rodriques, Edward Ross, Al Silverman, John Spooner, and Christina Ward.

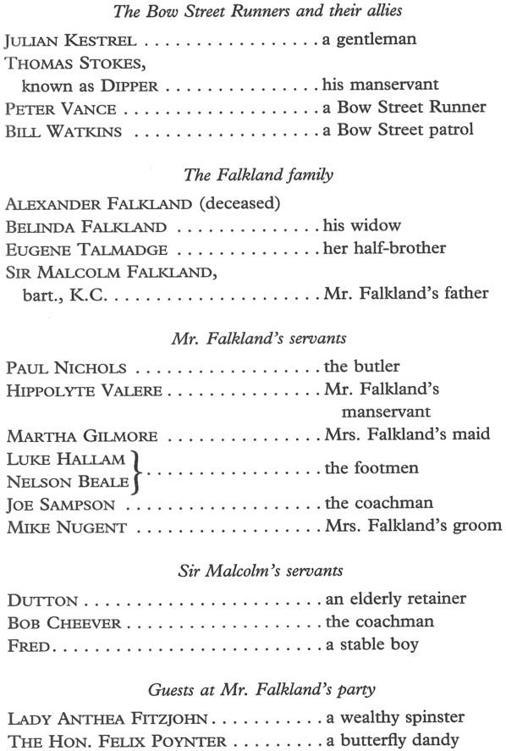

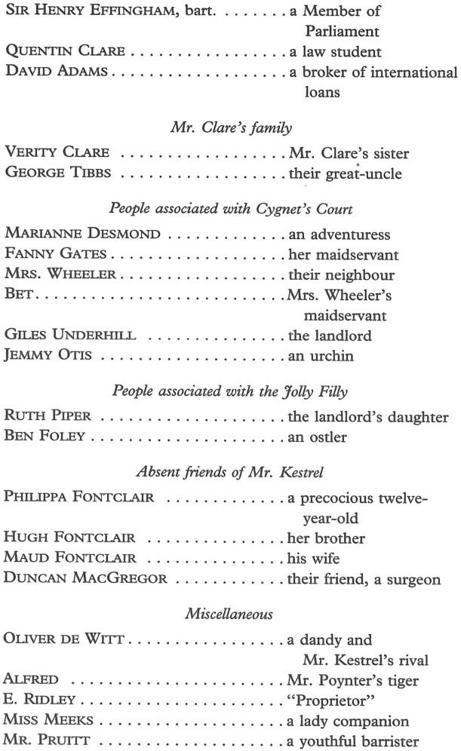

CHARACTERS

1: The Ring in the Fish

Go through the holly archway,

Sir Malcolm's letter had said,

then take the long, straight path past the church.

Well, this must be the archway, cut into a cluster of holly trees beside the church tower. The opening was narrow; Julian parted the shiny, spiky leaves with his riding whip and stepped through.

He found himself in a small, hilly churchyard, covered with a fantastic growth of foliage. There were more holly trees, great clumps of rhododendron, and shocks of unkempt grass overrun with ivy. Birds sang unseen from high branches; swarms of midges filled the air. Occasionally a bumblebee sailed by, as slow and stately as a barge. Weathered gravestones stood in disorderly ranks, some all but smothered in the rampant growth of vines and shrubs, others rising starkly above the greenery—the only dead things in a landscape teeming fiercely, incongruously, with life.

Julian glanced about in search of the path he was supposed to follow. There were so many footways swerving through the graves, around the bushes, and up and down the diminutive hills. Finally he spied a path that unfurled itself into a long, narrow lane. He set off, watched furtively by some half-dozen bystanders strolling among the graves. Despite Hampstead's proximity to London and its growing colony of artists and professional men, it was too small not to take an interest in a stranger—especially a young man dressed in the very pink of West End elegance.

The weather was typical of early May: chilly except when the afternoon sun fought its way through masses of grey and white cloud. It did so now, warming the air surprisingly swiftly, and turning the dull jade foliage a pale, brilliant green. Julian followed the path to what seemed to be the end, then it suddenly veered right, and he saw a man standing in a patch of sunshine just beyond a gnarled old tree.

He was forty-five or fifty, generously built, with a large head, broad shoulders, and sturdy limbs. His clothes were dark and sombre, and there was a wide black crape band on his hat. When he saw Julian, he waved eagerly and took a step as if to meet him. Then he checked himself, glanced down at a headstone at his feet, and stayed where he was, as if loath to leave the grave behind.

Julian went up to him. "Sir Malcolm?"

"Mr. Kestrel!" Sir Malcolm grasped his hand. "Thank you for coming."

"Not at all. I'm glad of an opportunity to meet you. I've heard a great deal about your prowess in court."

Sir Malcolm shook his head. "Oh, it's no great matter to confuse a jury sufficiently to win a case now and then. Still, I'm relieved the world remembers me for something besides —this."

He looked down at the headstone. It was a simple slab of white marble, untouched as yet by the weather, and only just caressed at its base by the encroaching grass. The inscription read:

ALEXANDER JAMES FALKLAND

born 1800, died 1825

WHOM THE GODS LOVE DIE YOUNG

"We weren't sure what to do about the dates," Sir Malcolm said quietly. "We don't know if he was killed before or after midnight. In the end, I decided to leave off the months and days altogether."

I decided,

Julian thought. Did that mean Alexander's widow had left it to Sir Malcolm to choose the inscription? Perhaps she was too overcome by grief; her husband had been murdered only a little over a week ago. Certainly that last line was more likely to be Sir Malcolm's idea than hers. He was said to be a first-rate classical scholar.

"How is Mrs. Falkland?" Julian asked.

"As well as can be expected. No—why should I put on a brave face with you? I intend you should be in my confidence. The fact is, she's in a very bad way. I mentioned in my note to you yesterday that she's been ill—a sudden indisposition, alarming at the time but, thank Heaven, it seems to have passed. It's the wound in her heart that's sapped her strength, blasted her youth. She's in despair, Mr. Kestrel. And she makes one understand that 'despair' is just what the Latin root conveys: the absence of all hope. She doesn't speak of it, but I know. She no longer believes that life has anything to offer her."

"Surely time will help assuage her feelings. No one can live long without hope—it isn't human nature."

"We live in the here and now, Mr. Kestrel. And in the here and now, she has to feel this way, and I have to see her every day, and know I can do nothing for her. And I have to grapple with my own demons: the rage, the frustration, of knowing that my son lies here, and justice goes in search of the villain who murdered him, and finds—nothing! We don't know by whom he was killed—worse still, we don't even know why! It wasn't a robbery, it wasn't a duel, it wasn't anything that ordinary human experience could school us to understand or accept. That's what makes it all so terrible—that he should have been killed, brutally murdered, for no reason!"

"For no

apparent

reason," Julian corrected him gently. "Murderers invariably have a reason for what they do. Even madmen think they have a reason, though to sane people it may make no sense."

Sir Malcolm was looking at him intently. "I believe, Mr. Kestrel, that murder is a specialty of yours. I mean, that you have a knowledge of the subject."

"I've had some experience with it. In one case, I was staying in a house where a murder occurred and found myself over head and ears in the investigation. The second time, I happened on evidence that it seemed only I could put to effective use."

"And both times, you found out the murderer when no one else could."

"I had that good fortune, yes."

"Mr. Kestrel, I'll be frank: I'd heard of your skill at solving crimes, and it's on that account that I asked to see you. Of course it was a theatrical gesture, appointing a meeting at Alexander's grave. I'm afraid every barrister has a dash of the actor in him. But I knew we could talk in private here." He glanced around this part of the churchyard, which they had entirely to themselves. "I come here every day, and no one disturbs me." He shrugged sadly. "No one knows what to say."

Julian said delicately, "Do you mean that I might be of service to you somehow?"

Sir Malcolm hesitated. "Let me begin at the beginning. You knew Alexander, I suppose?"

"We ran into each other fairly often, and I went to a few of his parties. I can't say I knew him very well. He had a great many friends."

"Yes, he made friends very easily. I don't know most of them, myself. Alexander and I moved in very different circles. My friends are all lawyers and academics. He was in his element in the fashionable world, going to routs and balls and pleasure gardens. He excelled at all the gentlemanly pursuits —riding, hunting, cards—and he always knew what to say to gratify and amuse a lady. On top of everything else, he had good looks—I can say that without conceit, since he didn't get them from me." Sir Malcolm shook his head, marvelling. "When he was a boy, I used to ask myself where he came from. He was beautiful and strange, like some exotic bird that, for reasons utterly baffling to me, had decided to nest in my house."

"What about his mother? Does he take after her?"

"Oh, no. Agnes was as shy and quiet a girl as you'd ever meet. Alexander never knew her, anyway—she died soon after he was born."

"He followed in your footsteps in one respect," Julian pointed out. "He was reading for the Bar, wasn't he?"

"Yes." A reminiscent glow lit Sir Malcolm's face. "He would have made a fine lawyer, and I would have done everything in my power to advance him. But he was also thinking about a career in politics, and that might have suited him even better."

Julian was inclined to agree. Politics would have made the most of Alexander's gifts: his charm, his verbal facility, his genius for getting on with a wide variety of people.

"Of course," Sir Malcolm went on, "a Parliamentary career requires money. But Alexander was never at a loss for that. He'd married an heiress, and, as you probably know, he had a knack for investing money. When I was his age, no gentleman would have had anything to do with the Stock Exchange, but speculation seems to be all the rage these days. Alexander conjured money out of nothing and scattered it in all directions, and everywhere it fell, something beautiful sprang up: his house, his art collection, his carriages, his entertainments.

"Of course I was proud of him, and rejoiced in his success. It's odd, isn't it? how you can read and write about a subject all your life, and never once apply it to your own experience. The great classical works are full of warnings about the danger of being too beloved by the gods. Do you remember the story of Polycrates?"

"I know he turns up in a poem of Byron's."

"He also turns up in Herodotus's

Histories.

He was the ruler of the island of Samos, famous for his power and wealth. He had an immense fleet, won every battle, filled his coffers with plunder and his enemies' hearts with fear. One day his friend Amasis warned him that the gods are envious of success, and advised him to find a way to break his long run of luck. So Polycrates took the thing he most treasured, an emerald ring, and threw it into the sea. A few days later, a fisherman presented him with an immense fish he had caught, and when its belly was slit open, the ring was found inside. Then Amasis knew for certain that his friend would die a terrible death, and, sure enough, Polycrates was captured by a Persian official and crucified."