Why Growth Matters (21 page)

Read Why Growth Matters Online

Authors: Jagdish Bhagwati

A slightly different version of this argument is that farmers simply do not want to sell their land. Therefore, no acquisition is possible unless the government is involved in the process. This is a specious argument, as numerous acquisitions in the states of Gujarat, Haryana, Punjab, Tamil Nadu, and Karnataka testify. More interestingly, Sukumaran and Bisoi (2011) report the interesting case in which the chief minister of Karnataka issued a statement on July 27, 2011, that no land acquisition was possible for the POSCO steel project in his state. Soon after, several farmers petitioned the chief minister to reconsider his decision. The petitioning farmers were aware that industrial developers in Karnataka, including the public-sector company NTPC, had paid lucrative prices for the land they acquired and did not want to be deprived of it. Within two days, on July 29, 2011, the chief minister reversed his decision.

Advocates of landowner rights argue that excluding government from land acquisition for private projects would result in the exploitation of landowners by industrialists. They argue that many small farmers do not know the value of their land or the laws governing their rights, leaving them vulnerable. While no one would deny that it is important to protect the rights of the small farmers in land transactions, if recent agitations surrounding the government's own forced acquisition at below-market

prices is any guide, landowners do have a keen sense of the value of their land. When the acquisition is done at below-market prices, NGOs in India are quick to get into the act on behalf of the owners. Moreover, mandatory advertisements of the prevailing prices by the buyer of large tracts of land offer a better solution to the imperfect information problem. The problem can also be alleviated through public posting of guidance prices by the relevant revenue departments in the state.

Two arguments have been made against

any

acquisition or purchase of farmland for nonfarm purposes, whether public or private. First, some advocates of farmer interests argue that nothing can compensate the farmers for the loss of their livelihood if their farms are sold. But it surely is possible to invest the proceeds from the sale of land in an annuity that guarantees the farmer an income stream equivalent to what he or she would have generated on average by working the land.

3

Second, some food-security advocates contend that deploying farmland into alternative uses would undermine India's food security. But the impression that nonagricultural users of land have been diverting much of the land in India from agriculture is false. Based on the latest available data, which relate to the year 2006â2007, nonagricultural uses of land, such as housing, establishments for industry and services, roads, railways, ports, and airports, together account for only 8.4 percent of India's land area. In contrast, the net area under cultivation accounts for 45.8 percent of the total area.

4

Even if we think in terms of expanding the land area under nonagricultural activities by 20 percent, it amounts to raising it by 1.7 percentage points to 10.1 percent of the total land area. In principle, a significant part of this area could come from barren land. But even if all of it were to come from agriculture, it would imply a reduction in area under agriculture from 45.8 percent to 44.1 percent of the total land area. Given that agriculture in India exhibits huge inefficiencies and is characterized by much lower productivity than in countries such as China, there is enormous scope for making up for the small reduction in area by raising productivity. Moreover, there is no reason India cannot count on satisfying a part of its demand for food through imports.

Infrastructure

T

he need for building twenty-first-century infrastructureâmulti-lane highways, all-weather rural roads, railway lines, airports, ports, telecommunications, well-functioning cities, and electricityâis well recognized. In fact, the theme of infrastructure enhancement characterizes even the United States today, where the difference among politicians is over the magnitude of stimulus spending but not over whether it ought to be on infrastructure, which is widely considered to be in need of repair: “London Bridge Is Falling Down” is more like a lament than a nursery rhyme.

India is not afflicted by the “curse” that often arises when infrastructure is built ahead of the growth that would require it. The existence of roads, for example, does not guarantee that commerce will develop along them. It is often forgotten, especially in some African countries where aid agencies and recipient governments wish to spend money on building roads and ports, that simply building infrastructure will not automatically generate economic growth that would then give rise to the necessary demand for infrastructure. In such cases, we are putting the cart before the horse. Fortunately, growth has occurred in India, and the demand for infrastructure is running well ahead of its current supply.

1

Given this consensus on the need for improved and increased provision of infrastructure along various dimensions, the issues before the Track I reformers therefore mostly have to do with “how to manage and deliver.” With the possible exception of telecommunications, as in the developed countries, infrastructure in different sectors and areas will

require the public sector to take the lead even as it seeks the participation of the private sector through public-private partnerships. The main possible difference is that the governments in some developed countries are perhaps more capable than has been the case in India in recent years, necessitating greater participation of the private sector.

The issues are manifold but here we focus only on those that bear on the task of intensifying Track I reforms.

2

Regarding air transport, progress has been notable in the construction of modern airports in New Delhi, Mumbai, Hyderabad, Ahmedabad, Bangalore, and even some smaller towns, such as Jaipur. At the same time, satisfactory progress has been made in building associated airtransport infrastructure.

The key pending reform in this area concerns Air India, which absorbed more than $10 billion in subsidies in 2010â2011 alone.

3

The government must give serious consideration to privatizing the airline. Jet Airways, which runs a superb international service, provides an excellent model.

In the construction of highways, while there have been issues of financing, an equally important bottleneck has been the lack of coordination among various arms of the government. Under the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) government, which originally launched in December 2000 the ambitious National Highway Development Program to convert the Golden Quadrilateral highway into four lanes, the issuing of contracts to completion under Phase I of the program was substantially accomplished within just four years.

Despite this excellent beginning, the highway construction program languished under the United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government. The Planning Commission practically banned the National Highway Authority of India from issuing new contracts from early 2005 to at least

the end of 2006 on the grounds that the contract the NDA had used was flawed and a new Model Concession Agreement was required.

4

Even after the Planning Commission came out with a new agreement in late 2006, the contracting process could not move forward smoothly.

The situation has subsequently improved only marginally. As late as July 2010, exasperated Road Transport Minister Kamal Nath, who had wanted to accelerate highway building to twenty kilometers per day, stated at a seminar on highways, “When I joined this ministry, everyone told me that the Planning Commission will never let you do it.” He went on to describe the commission as “an armchair advisor,” noting that the commission was unfamiliar with the ground reality. He elaborated: “Building a road in Kerala is different from building a road in Madhya Pradesh. We must have a concept that is flexible. Public-private partnership for Kerala has to be different from Madhya Pradesh.”

5

Such encounters clearly illustrate the detrimental effect of a lack of coordination among various arms of the government. There is nothing inherently difficult about building roads and bridges. The prime minister should take steps to coordinate the various arms of the government to ensure that the country works coherently to accelerate the road-building program.

6

Perhaps the infrastructure problem that needs most urgent and concerted attention is power. Power shortage is a critical handicap when India has an ambition to sustain 8â9 percent annual growth. Low-cost electricity is required to keep labor-intensive products competitive due to generally low profit margins in the latter. This would make growth more inclusive, as we demonstrated earlier.

But power is also necessary because in India we must bring electricity to those living in rural areas. The provision of electricity in rural areas is important not only for making day-to-day existence more comfortable but also for stimulating entrepreneurial activity locally.

Although the 2003 Electricity Act initiated a major reform in the power sector, unfortunately, the process appears to have come to a near

standstill with even a reversal (with respect to cross-subsidy in electricity tariffs) under the UPA government. Per capita consumption of electricity is very low and rising extremely slowly.

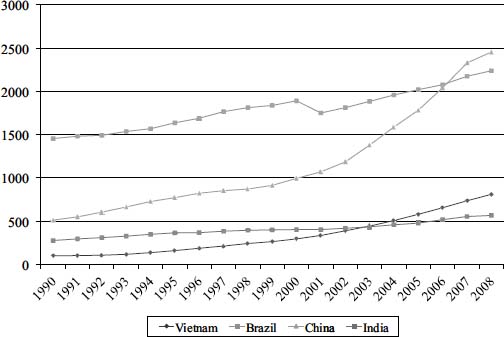

Figure 10.1

, which makes some pertinent cross-country comparisons, illustrates this sharply.

Figure 10.1. Per capita annual electricity consumption in kilowatt hours

Source: World Development Indicators of the World Bank online (accessed November 7, 2012)

The figure shows that both Brazil and China have much higher consumption of electricity in per capita terms than India. Besides, the gap between them and India has steadily widened since 1990. From approximately one-half of China's consumption per capita in 1990, India dropped to less than a quarter of it in 2008. What is even more disappointing is that Vietnam, which consumed a little more than one-third of India's amount in 1990, had reached almost one and a half times India's level by 2008.

Finally, India also needs to make a concerted effort to build its urban infrastructure. Urbanization is an integral part of modernization, and

this requires well-functioning cities. With the possible exception of New Delhi, few Indian cities function well today. Traffic jams, potholed roads, and the absence of a mass rapid-transit system characterize major Indian cities, such as Bangalore and Mumbai. Slow movement in and out of cities in turn contributes to the phenomenon of workers' having to find living space within the city, fueling in turn the growth of slums.

An important source of the problem in Indian cities has been their horizontal nature, a phenomenon reinforced by tight restrictions on the floor-space index, which specifies the maximum floor space that can be created on a plot of given size.

7

Relaxing the floor-space index and, thus, allowing taller buildings can release valuable space for widening the roads and building mass rapid transit aboveground. It can also help build a vibrant city center that minimizes the time lost in going from one office to the other. States that have not yet repealed the Urban Land Ceilings Act of 1976, most notably Maharashtra, need to do so. And above all, issues of uninterrupted water and electricity supply and public health need to be tackled.

Higher Education

H

igher education reforms are necessary in a fast-growing economy, which requires an increasing volume of skilled workers, a steady stream of innovation of new products and processes, and the progressive adaptation of technologies already available from past research in other countries. But these reforms also offer a double dividend because, by improving the educational access of millions of those who aspire to partake of the opportunities opened up by the growth-enhancing post-1991 reforms, they increase the inclusiveness of the growth.

It would be an understatement to say that the higher education system in India is in a crisis. Except for a handful of institutions, the poor quality of instruction in the classroom is a well-known handicap afflicting India whether we consider public or private institutions. True, universities and colleges have an adequate and broadly uniform curriculum and, recognizing the high returns to good college performance, better students manage to do well by mastering it. But the quality of instruction in the classroom is far from satisfactory; indeed it is often poor.

International rankings of universities reflect this situation as well. In the QS World University Rankings released in September 2011, no Indian university including the celebrated Indian Institutes of Technology found a place among even the top two hundred. In contrast, universities from several other Asian countries, such as China, Japan, Hong Kong, Singapore, and Taiwan, managed to be ranked among the top one hundred.