Why the West Rules--For Now (39 page)

Read Why the West Rules--For Now Online

Authors: Ian Morris

Tags: #History, #Modern, #General, #Business & Economics, #International, #Economics

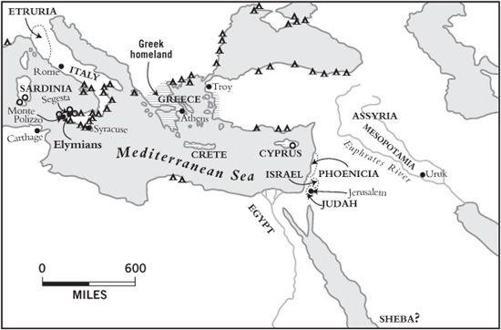

Figure 5.3. Low-end kingship in the West: sites of the first half of the first millennium

BCE

mentioned in the text. Triangles mark major Greek colonies; open circles, major Phoenician colonies. The Greek homeland is shaded.

The first part of the Western core to revive after the dark age may have been Israel, where, the Hebrew Bible says, the tenth-century

BCE

kings David and Solomon created a “United Monarchy” stretching from the borders of Egypt to the Euphrates. Its capital at Jerusalem boomed, we are told, and Solomon feted the queen of distant Sheba (perhaps in Yemen) and sent trading missions across the Mediterranean. While smaller and weaker than the International Age kingdoms, the United Monarchy sounds more centralized than the contemporary Zhou family business, extracting taxes and drawing in tribute from all around. It may have been the strongest state in the world until its components, the peoples of Israel and Judah, abruptly parted ways on Solomon’s death around 931

BCE

.

Unless, that is, none of these things actually happened. Many biblical scholars believe there was no United Monarchy. The whole thing

was a fantasy, they argue, dreamed up by Israelites centuries later to console themselves about the dire situation in their own day. Archaeologists have certainly had trouble finding the great building projects that the Bible says David and Solomon undertook, and debates have become alarmingly fierce. In the normal run of things, even the most dedicated archaeologists have been known to doze off in seminars about the chronology of ancient storage vessels, but when one archaeologist suggested in the 1990s that pots normally dated to the tenth century

BCE

were in fact made in the ninth century—which would mean that monumental buildings previously associated with Solomon, in the tenth century, must also date a hundred years later, in turn meaning that Solomon’s kingdom was a poor and undistinguished place and the Hebrew Bible has the story wrong—he provoked such rage that he had to hire a bodyguard.

These are troubled waters. Not having a bodyguard, I will get out of them quickly. It seems to me that the biblical account, like the Chinese traditions about the Xia and Shang discussed in

Chapter 4

, may be exaggerated but is unlikely to be totally fanciful; and evidence from other parts of the Western core also suggests that revival was under way by the late tenth century

BCE

. In 926 Sheshonq I, a Libyan warlord who had seized the Egyptian throne, led an army through Judah (the southern part of modern Israel and the West Bank) in what looks like an attempt to restore the old Egyptian Empire. He failed, but in the north a still greater power was also stirring. After a hundred-year gap during the dark age, Assyrian royal records restarted in 934

BCE

under King Ashur-dan II, giving us a glimpse of a gangster state that made the Zhou look angelic.

Ashur-dan was very conscious that Assyria was recovering from a dark age. “

I brought back

the exhausted peoples of Assyria who had abandoned their cities and houses in the face of want, hunger, and famine, and had gone up to other lands,” he wrote. “I settled them in cities and houses … and they dwelt in peace.” In some ways Ashur-dan was an old-fashioned king, seeing himself as the earthly representative of Assyria’s patron god Ashur, much as Mesopotamian kings had been doing for two thousand years. Ashur, though, had had a makeover during the dark age. He had become an angry god; in fact, a very angry god, because although

he

knew he was top god, most mortals failed to grasp this. Ashur-dan’s job was to make them grasp it by turning the

world into Ashur’s hunting ground. And if hunting for Ashur made Ashur-dan rich, that was fine too.

Within Assyria’s heartland the king commanded a small bureaucracy and appointed governors called Sons of Heaven, giving them huge estates and labor forces. These were high-end practices that would have been familiar to any International Age ruler, but the Assyrian king’s real power had low-end sources. Rather than taxing Assyria to pay for an army to do Ashur’s hunting, the king relied on the Sons of Heaven to provide troops, rewarding them—as Zhou kings did with their lords—with plunder, exotic gifts, and a place in royal rituals. The Sons of Heaven leveraged this position to win thirty-year terms of office, effectively turning their estates into hereditary fiefs and their laborers into serfs.

Just like Zhou rulers, Assyrian kings were hostages to the lords’ goodwill, but so long as they won wars that did not matter. The Sons of Heaven provided much bigger armies than Zhou vassal kings (according to royal accounts, fifty thousand infantry in the 870s

BCE

and more than a hundred thousand in 845, plus thousands of chariots), and the kings’ relatively high-end bureaucracy provided the logistical support to feed and move these hosts.

Not surprisingly, the rulers of Assyria’s smaller, weaker neighbors generally preferred buying protection to being impaled on pointed sticks while their cities burned. An offer from the Assyrians was normally one they couldn’t refuse, particularly since Assyria often left submissive local kings in power rather than using the Zhou strategy of replacing them with colonists. Defeated kings could even end up profiting; if they loaned Assyria troops for its next war, they could get a cut of the plunder.

Client kings might be tempted to back out of their deals, though, so Assyria focused their minds with holy terror. Those who submitted did not have to worship Ashur, but they did have to recognize that Ashur ruled heaven and told their own gods what to do—which made rebellion a religious offense against Ashur as well as a political one, giving the Assyrians no choice but to punish it as savagely as possible. Assyrian kings decorated their palaces with carved scenes of horrific brutality, and their glee in cataloguing massacres rapidly becomes mind-numbing. Take, for instance, Ashurnasirpal II’s account of the punishments meted out to rebels around 870

BCE

:

I built a tower

over against his city gate and I flayed all the chiefs who had revolted, and I covered the tower with their skin. Some I walled up within the tower, some I impaled upon the tower on stakes, and others I bound to stakes around the tower …

Many captives from among them I burned with fire, and many I took as living captives. From some I cut off their noses, their ears, and their fingers, of many I put out the eyes. I made one pile of the living and another of heads, and I hung their heads from tree trunks round about the city. Their young men and maidens I burned up in the fire. Twenty men I captured alive and I walled them up in his palace … The rest of the warriors I consumed with thirst in the desert.

The political fortunes of the Eastern and Western cores were moving in different directions in the ninth century

BCE

, with Zhou rule unraveling while Assyria was reviving after the dark age, but both cores experienced constant warfare, growing cities, more trade, and new, low-cost ways to run states. And in the eighth century

BCE

they found something else in common: both discovered the limits of kingship on the cheap.

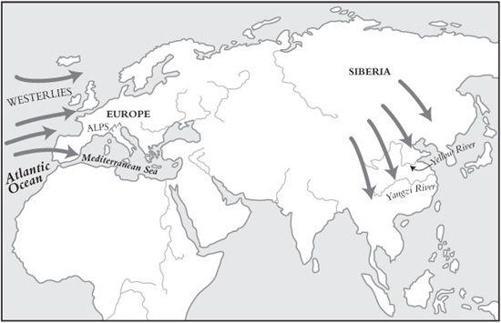

THE WINDS OF CHANGE

It’s an ill wind, the saying goes, that blows nobody any good. Never was this truer than around 800

BCE

, when minor wobbles in Earth’s axis generated stronger winter winds all over the northern hemisphere (

Figure 5.4

). In western Eurasia, where the main winter winds are “westerlies” blowing from the Atlantic, this meant more winter rain. This was good for people in the Mediterranean Basin, where the commonest cause of death had always been intestinal viruses that flourish in hot, dry weather, and the main problem for farmers was that the winter winds might not bring enough rain for good harvests. Cold and rain were better than sickness and hunger.

The new climate regime was bad, though, for people north of the Alps, where the main killers were respiratory diseases that flourished in the cold and damp and the main agricultural problem was a short summer growing season. As the weather changed between 800 and 500

BCE

population fell in northern and western Europe but rose around the Mediterranean.

Figure 5.4. The chill winds of winter: climate change in the early first millennium

BCE

In China the winter winds blow mainly from Siberia, so when they grew stronger after 800

BCE

they made the weather drier as well as cooler. This probably made agriculture easier around the Yangzi and Yellow rivers by reducing flooding, and population kept growing in both valleys, but it made life harder for people on the increasingly arid plateau north of the Yellow River.

Within these broad patterns there were countless local variations, but the main result was like the episodes of climate change we saw in

Chapter 4

; the balances within and between regions shifted, forcing people to respond. The author of a standard textbook on paleoclimatology says of these years, “

If such a disruption

of the climate system were to occur today, the social, economic, and political consequences would be nothing short of catastrophic.”

In East and West alike the same amount of land had to feed more mouths as population grew. This generated both conflicts and innovations. Both could potentially be good for rulers; more conflicts meant more chances to help friends and punish enemies, more innovations

meant more wealth being generated, and the engine behind both—more people—meant more laborers, more warriors, and more plunder.

All these good things could come to kings who kept control, but the low-end kings of the eighth century

BCE

found that difficult. The big winners, best placed to exploit new opportunities, were often local bosses—the governors, landlords, and garrison commanders on whom low-end kings relied to get things done. This was bad news for kings.

In the 770s

BCE

Eastern and Western kings alike lost control of their vassals. The Egyptian state, more or less unified since 945

BCE

, split into three principalities in 804 and devolved by 770 into a dozen virtually independent dukedoms. In Assyria, Shamshi-Adad V had to fight to secure his succession to the throne in 823

BCE

, then lost control of his client kings and governors. Some Sons of Heaven even waged wars in their own names. Assyriologists call the years 783 through 744

BCE

“the interval,” a time when kings counted for little, coups were common, and governors did what they liked.

For local aristocrats, minor princes, and little city-states, this was a golden age. The most interesting case is Phoenicia, a string of cities along the modern Lebanese coast, whose inhabitants had been prospering as middlemen since the Western core revived in the tenth century

BCE

, carrying goods between Egypt and Assyria. Their wealth attracted Assyrian attention, though, and by 850 the Phoenicians were paying protection money. Some historians think this pushed Phoenicians to venture into the Mediterranean in search of profits to buy peace; others suspect that the growing population and pull of new markets in the Mediterranean was more important. Either way, by 800

BCE

Phoenicians were voyaging far afield, setting up trade enclaves on Cyprus and even building a little shrine on Crete. By 750 the Greek poet Homer could take it for granted that his audience knew (and mistrusted) “

Phoenician men

, famous for their ships, gnawers at profit, bringing countless pretty things in each dark hull.”

The Greek population grew fastest of all, though, and Phoenician explorers and traders may have pulled hungry Greeks along in their wake. By 800

BCE

someone was carrying Greek pottery to southern Italy, and by 750 Greeks as well as Phoenicians were settling permanently

in the western Mediterranean (see

Figure 5.3

). Both groups liked good harbors with access via rivers to markets in the interior, but the Greeks, who came in much greater numbers than the Phoenicians, also settled as farmers and grabbed some of the best coastal land.