Why the West Rules--For Now (46 page)

Read Why the West Rules--For Now Online

Authors: Ian Morris

Tags: #History, #Modern, #General, #Business & Economics, #International, #Economics

Their migrations created a domino effect. In the eighth century

BCE

a group called the Massagetae migrated west across what is now Kazakhstan, confronting the Scythian people in their path with the same choice that prehistoric hunter-gatherers had had to make when farmers moved into their foraging lands or Sicilian villagers had had to make when Greek colonists landed on their coasts: they could stand their ground, organizing themselves to fight back and even electing kings, or they could run away. Those who yielded fled across the Volga River, presenting the Cimmerians who already lived there with the same fight-or-flight choice.

In the 710s

BCE

bands of Cimmerian refugees started moving into the Western core. There were not many of them, but they could do a lot of damage. In agrarian states, many peasants have to toil in the fields to support a few soldiers. At the height of their wars, Rome and Qin had mobilized maybe one man in six, but in peacetime they mustered barely one in twenty. Among nomads, by contrast, every man (and many a woman, too) could be a warrior, born and raised with a horse and bow. This was the original example of asymmetric warfare. The great empires had money, quartermasters, and siege weapons, but the nomads had speed, terror, and the fact that their sedentary victims were often busy fighting one another.

In these years climate change and rising social development once again combined to disrupt the Western core’s frontiers, and violence and upheaval were once more the results. The Assyrian Empire, which was still the greatest power in the West around 700

BCE

, invited the Cimmerians into the core to help it fight its rivals. At first that worked well, and in 695

BCE

King Midas of Phrygia in central Turkey, so rich that Greek legends said he could turn objects to gold just by touching them, committed suicide as the Cimmerians closed in on his capital.

By eliminating buffer states such as Phrygia, though, the Assyrians exposed their heartland to nomad raids, and by 650

BCE

Scythians virtually controlled northern Mesopotamia. Their “

violence and neglect

of law led to total chaos,” the Greek historian Herodotus wrote. “They acted like mere robbers, riding up and down the land, stealing everyone’s

property.” The nomads destabilized the Assyrian Empire and helped the Medes and Babylonians sack Nineveh in 612

BCE

, then immediately turned on the Medes, too. Not until about 590

BCE

did the Medes figure out how to fight such wily, fast-moving foes—according to Herodotus, by getting their leaders drunk at a banquet and murdering them.

The kings of Media, Babylon, and Persia experimented with how to handle nomads. One option was to do nothing, but then nomad raids ruined frontier provinces, cutting the tax take. Buying the nomads off was another possibility, but paying protection could get as pricey as being raided. Preemptive war was a third response, striking into the steppes and occupying the pastures nomads needed to survive, but that was even costlier and riskier. With little to defend, nomads could retreat into the treeless, waterless waste, luring the invaders to destruction when their supplies ran out.

Cyrus, the founder of the Persian Empire, tried preemptive war against the Massagetae in 530

BCE

. Like the Medes before him, he fought with the grape: he let the Massagetan vanguard loot his camp, and when they were drunk, slaughtered them and captured their queen’s son. “

Glutton as you are

for blood,” Queen Tomyris wrote to Cyrus, “give me back my son and get out of my country with your forces intact … If you refuse, I swear by the sun our master to give you more blood than you can drink.” True to her word, Tomyris defeated the Persians, cut off Cyrus’ head, and stuffed it in a bag of gore.

It was a bad start for preemptive strikes, but in 519

BCE

Darius of Persia showed that they could work, defeating a confederation that Persians called the “Pointy-Hatted Scythians” and imposing tribute and a puppet king on them. Five years later he tried it again, crossing the Danube and pursuing other Scythians deep into Ukraine. But like so many asymmetric wars in our own day, it is hard to say who won. Herodotus thought it was a disaster, from which Darius was lucky to escape alive, but the Scythians never again threatened Persia, so clearly something went right.

It took longer for cavalry from the steppes to become a fact of life in the East, just as it had taken chariots longer to reach China than the West, but when the nomadic domino effect did arrive it worked just as viciously. The eastward spread of nomadism had probably been behind the Rong people’s attacks on the Zhou in the eighth century

BCE

, and

the northern people absorbed by the states of Qin and Jin in the seventh and sixth centuries

BCE

must often have been choosing assimilation over fighting incoming nomads. When they did so, the combined pressure of nomad incursions and Chinese states’ expansion eliminated buffer societies, just as had happened in the West.

The state of Zhao now became the frontier. Like the Assyrians when they faced the Scythians, Zhao immediately recruited nomadic horsemen to fight its neighbors and trained its own subjects as cavalry. Zhao also developed an antinomad strategy little used in the West, the war of attrition, building walls to keep nomads out (or at least to channel where they traded and raided). This seemed to work less badly than fighting or paying protection, and in the third century

BCE

walls proliferated. The Qin First Emperor’s wall stretched for two thousand miles, costing (according to legend, anyway) one laborer’s life for every yard built.

*

Being the kind of man he was, the First Emperor lost no sleep over this. In fact, he so appreciated wall-building that he turned this defensive strategy into a weapon, extending his Great Wall to enclose a vast sweep of pasture where nomads had traditionally grazed. Then, in 215

BCE

, he followed up with a preemptive war.

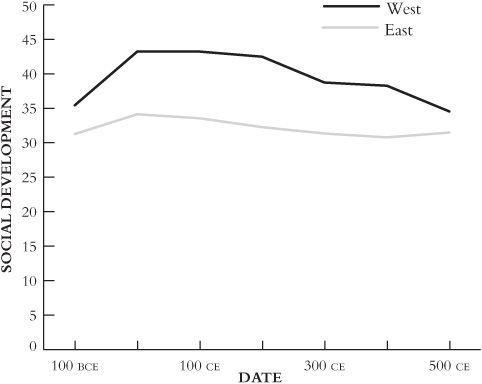

The Great Wall sent a clear signal: geography was changing meaning again. The forces that drove the dull upward march of social development in

Figure 5.1

—rising energy capture, more effective organization, widespread literacy, ever-deadlier armies—were transforming the world. By 200

BCE

a single great empire dominated each core, its warriors and traders reaching even into the spaces between the cores. The steppes had gone from being a vast barrier between East and West to a highway linking them, and instead of separate but similar histories, the Eastern and Western cores were beginning to be intertwined. Very few goods, people, or ideas were as yet traveling the whole way from one end of Eurasia to the other, but new geographical realities were taking shape. Over the next few centuries, these would sweep away the great empires that dominated the cores in 200

BCE

, throw the upward trends of social development into reverse, and end the West’s lead. The paradox of development was entering a whole new phase.

6

DECLINE AND FALL

ALL FOR THE BEST

“

All is for

the best in this best of all possible worlds,” says Dr. Pangloss—again, and again, and again—in Voltaire’s eighteenth-century comic classic

Candide

. Despite contracting syphilis, losing an eye and an ear, and being enslaved, hanged, and caught in not one but two earthquakes, Pangloss sticks to his story.

Pangloss, of course, was Voltaire’s little joke, poking fun at the silliness of contemporary philosophy, but history has thrown up plenty of real-life versions. The great empires that dominated the Eastern and Western cores in the first few centuries

CE

seem to have been especially rich in them. “

When the emperor

makes his imperial tour, all is resplendent,” one Chinese poet wrote. “Boundless joy reigns for ten thousand years.” In the Roman Empire the Greek orator Aristides waxed even more enthusiastic. “

For the eternal

duration of the empire the whole civilized world prays all together,” he declaimed. “Let all the gods grant that this empire and this city flourish forever and never cease until stones float on the sea and trees cease to put forth shoots.”

So what would these Panglosses have made of

Figure 6.1

? After peaking around 1

BCE/CE

, social development fell in both East and West. This was collapse on a whole new scale. Not only was it broader

than ever before, affecting both ends of Eurasia, but it was also longer and deeper. Century after century it dragged on, cutting more than 10 percent off the East’s development score by 400

CE

and 20 percent off the West’s by 500. How this happened, ushering in the end of the West’s fourteen-thousand-year-long lead in social development, is this chapter’s subject.

Figure 6.1. An Old World–wide depression: the peak, decline, and fall of the ancient empires, 100

BCE

–500

CE

THE NEW WORLD ORDER

The ancient empires had not always been full of Panglosses. It took hundreds of years of wars and millions of deaths before the paradox of violence that I mentioned in

Chapter 5

—the fact that war eventually brought peace and prosperity—made itself clear; and no sooner had the wars of unification ended than the Qin and Roman superstates both turned on themselves in horrific civil wars. Qin got down to this immediately; Rome, more gradually.

Qin’s centralized, repressive institutions had been magnificent for conquering but turned out to be less good for ruling. After vanquishing

his last enemies in 221

BCE

the First Emperor continued conscripting all his male subjects, now setting them to building instead of fighting. Sometimes they were productive, as when they laid thousands of miles of roads and canals; sometimes less so. Sima Qian says that despite convincing himself of his own divinity and spending several fortunes on quacks who promised to make him live forever, the First Emperor—perhaps as insurance—also had 700,000 men spend thirty-six years building his tomb. (The graves of hundreds who died at the site have been excavated.)

The (mostly unexcavated) twenty-square-mile tomb complex is China’s answer to Egypt envy. It is best known

today

for the Terracotta Army, six-thousand-plus life-size clay soldiers that guarded it, discovered by chance by a work team digging wells in 1974. It is one of the archaeological wonders of the world, but even more astonishing is the fact that when Sima Qian described the First Emperor’s tomb, this Terracotta Army that has astonished museum visitors around the world did not even get a mention. Sima instead saved his words for the tomb’s underground bronze palace, four hundred yards across, surrounded by replicas of the kingdom’s rivers in mercury. (Geochemical surveys in 1981 and 2003 confirmed that the soil above the tomb has massively elevated mercury levels.) All those royal concubines who had not given the First Emperor children, Sima Qian says, plus all the artisans who knew the tomb’s secrets and possibly the empire’s top hundred officials, too, were buried with the emperor in 210

BCE

.

The First Emperor’s megalomaniacal policies generated resistance at every level. When noblemen complained, he forcibly moved them to his capital; when intellectuals complained, he buried 460 of them alive; and when peasants complained, he cut them in half.

*

The reign of terror imploded almost the moment the First Emperor died. One day in 209

BCE

, the story runs, heavy rain prevented two lowly officials from delivering conscripts to a garrison on time. The penalty for lateness was, of course, death. “

As things stand

, we face death whether we stay or run away,” Sima Qian reports one of them saying, “while if we were to start a revolt we would likewise face death. Since

we must die in any case, would it not be better to die fighting for our country [by rebelling]?”