Why the West Rules--For Now (62 page)

Read Why the West Rules--For Now Online

Authors: Ian Morris

Tags: #History, #Modern, #General, #Business & Economics, #International, #Economics

The morning sun

not yet risen from the lake,

Bramble thickets seem for a moment like gates of pine.

Aged trees steep the precipitous cliffs in gloom;

The apes’ desolate calls float down.

The path turns, and a valley opens

With a village in the distance barely visible.

Along the track, shouting and laughing,

Come farmhands overtaking and overtaken in turn

Off to match wits a few hours at the market.

The lodges and stores are countless as the clouds.

They bring linen fabrics and paper-mulberry paper,

Or drive pullets and sucking-pigs ahead of them.

Brushes and dustpans are piled this way and that—

Too many domestic trifles to list them all.

An elderly man controls the busy trafficking,

And everyone respects his slightest indications.

Meticulously careful, he compares

The yardsticks one by one,

And turns them over slowly in his hands.

Urban markets were of course far grander and could draw on half a continent of suppliers. Southeast Asian traders linked the port of Quanzhou to the Indonesian Spice Islands and the riches of the Indian Ocean, and imports made their way from there to every town in the empire. To pay for them, family workshops turned out silks, porcelain, lacquer, and paper, and the most successful blossomed into factories. Even villagers could buy what had formerly been luxuries, such as books. By the 1040s, millions of relatively cheap books were rolling off wooden printing presses and making their way into even quite modest buyers’ hands. Literacy rates probably rivaled those of Roman Italy a thousand years earlier.

The most momentous changes of all, though, were in textiles and coal, exactly the spheres of activity that would drive the British industrial revolution in the eighteenth century. Eleventh-century textile workers invented a pedal-powered silk-reeling machine, and in 1313 the scholar Wang Zhen’s

Treatise on Agriculture

described a large hemp-spinning version, adapted to use either animal or waterpower. It was, Wang noted, “

several times cheaper

than the women it replaces,” and was “used in all parts of north China which manufacture hemp.” So moved was Wang by this wizardry that he interrupted his technical account with bursts of poetry:

It takes a spinner many days to spin a hundred catties,

But with waterpower it may be done with supernatural speed! …

There is one driving belt for wheels both great and small;

When one wheel turns, the others all turn with it!

The rovings are transmitted evenly from the bobbin rollers,

The threads wind by themselves onto the reeling frame!

*

Comparing eighteenth-century plans for a French flax-spinning machine with Wang’s fourteenth-century design, the economic historian Mark Elvin felt compelled to conclude that “

the resemblance to Wang [Z]hen’s

machine is so striking that suspicions of an ultimate

Chinese origin for it … are almost irresistible.” Wang’s machine was less efficient than the French one, “but,” Elvin concludes, “if the line of advance which it represented had been followed a little further then medieval China would have had a true industrial revolution in the production of textiles over four hundred years before the West.”

No statistics survive for Song-era textile production and prices, so we cannot easily test this theory, but we do have information on other industries. Tax returns suggest that iron output increased sixfold between 800 and 1078, to about 125,000 tons—almost as much as the whole of Europe would produce in 1700.

*

Ironworks clustered around their main market, the million-strong city of Kaifeng, where (among other uses) iron was cast into the countless weapons the army required. Chosen as a capital because it lay conveniently near the Grand Canal, Kaifeng was the city that worked. It lacked the history, tree-lined boulevards, and gracious palaces of earlier capitals and it inspired no great poetry, but in the eleventh century it grew into a crowded, chaotic, and vibrant metropolis. Its raucous bars served wine until dawn,

†

fifty theaters each drew audiences of thousands, and shops even encroached on the city’s one great processional avenue. And beyond the walls, foundries burned day and night, dark satanic mills belching fire and smoke, sucking in tens of thousands of trees to smelt ores into iron—so many trees, in fact, that ironmasters bought up and clear-cut entire mountains, driving the price of charcoal beyond the reach of ordinary homeowners. Hundreds of freezing Kaifengers were trampled in fuel riots in 1013.

Kaifeng was apparently entering an ecological bottleneck. There was simply not enough wood in northern China to feed and warm its million bodies and to keep foundries turning out thousands of tons of iron. That left just two options: the people and/or industries could drift away, or someone could innovate and find a new fuel source.

Homo sapiens

had always lived by exploiting plants and animals for food, clothes, fuel, and shelter. Over the ages humans had become much more efficient parasites; subjects of the Han and Roman empires

in the first centuries

CE

, for instance, consumed seven or eight times as much energy per person as their Ice Age ancestors had grubbed up fourteen thousand years earlier.

*

The Han and Romans had also learned to tap winds and waves to move boats, going beyond what plants and animals could do for them, and to apply waterpower to mills. Yet the cold Kaifengers who rioted in 1013 were still basically feeding off other organisms, standing little higher in the Great Chain of Energy than Stone Age hunter-gatherers.

Within a few decades that had begun to change, turning Kaifeng’s ironmasters into unwitting revolutionaries. A thousand years earlier, in the days of the Han dynasty, some Chinese had tinkered with coal and gas, but these energy sources had had few obvious applications. Only now, with the voracious forges competing with hearths and homes for fuel, did industrialists push hard at the door between the ancient organic economy and a new world of fossil fuels. Kaifeng was near two of China’s biggest coal deposits (

Figure 7.9

), with easy access via the Yellow River, so it did not take genius—just greed, desperation, and trial and error—to work out how to use coal instead of charcoal to smelt iron ore. It also took capital and labor to locate, dig up, and move the coal, which probably explains why businessmen (who had resources) rather than householders (who did not) led the way.

A poem written around 1080 gives a sense of the transformation. The first verse describes a woman so desperate for fuel that she sells her body for firewood; the second, a coal mine coming to the rescue; the third, a great blast furnace; and the fourth, relief that people can now have their cake and eat it: great iron swords can be cast but the forests will survive.

Didn’t you see her

,

Last winter, when travelers were stopped by the rain and snow,

And city-dwellers’ bones were torn by the wind?

With a half-bundle of damp firewood, “bearing her bedding at dawn.”

*

At twilight she knocked on the gate, but no one wanted her trade.

Who would have thought that in those mountains lay a hidden treasure,

In heaps, like black jewels, ten thousand cartloads of coal.

Flowing grace and favor, unknown to all.

The stinking blast—

zhenzhen

†

—disperses;

Once a beginning is made, [production] is vast without limit.

Ten thousand men exert themselves, a thousand supervise.

Pitching ore into the roiling liquid makes it even brighter,

Flowing molten jade and gold, its vigorous potency.

In the Southern Mountains, chestnut forests now breathe easy;

In the Northern Mountains, no need to hammer the hard ore.

They will cast you a sword of a hundred refinings,

To chop a great whale of a bandit to mincemeat.

Coal and iron took off together. One well-documented foundry, at Qicunzhen, employed three thousand workers to shovel 35,000 tons of ore and 42,000 tons of coal into furnaces each year, harvesting 14,000 tons of pig iron at the other end. By 1050 so much coal was being mined that householders were using it too, and when the government overhauled poor relief in 1098 coal was the only fuel its officials bothered to mention. Twenty new coal markets opened in Kaifeng between 1102 and 1106.

By then Eastern social development had risen as high as the peak reached in ancient Rome a millennium earlier. The West, split between a Muslim core and a Christian periphery, now lagged far behind, and would not match this level of social development until the eighteenth century, on the eve of Britain’s industrial revolution. Every indication

was, in fact, that a Chinese industrial revolution was brewing within Kaifeng’s soot-blackened walls and would turn the huge Eastern lead in social development into Eastern rule. History seemed to be moving down the path that would take Albert to Beijing rather than Looty to Balmoral.

8

GOING GLOBAL

THREE BIG THINGS

Everything about China amazed Marco Polo. Its palaces were the best in the world and its rulers the richest. Its rivers supported more ships than all the waters of Christendom combined, carrying more food into its cities than a European could imagine anyone eating. And what food it was, so subtle that Europeans could scarcely believe it. Chinese maidens excelled in modesty and decorum; Chinese wives were angelic; and foreigners who enjoyed the hospitality of the courtesans of Hangzhou never forgot them. Most amazing of all, though, was China’s commerce. “

I can tell you

in all truthfulness,” said Marco, “that the business … is on such a stupendous scale that no one who hears tell of it without seeing it for himself can possibly credit it.”

That, it turned out, was the problem. When Marco returned to Venice in 1295 many of those who thronged to hear his stories did not, in fact, credit them.

*

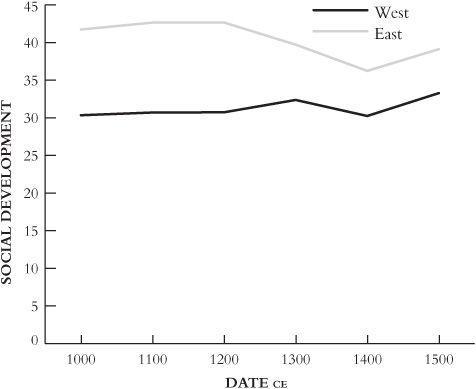

But despite its occasional oddities, such as pears that weighed ten pounds, Marco’s account is quite consistent with what we see in

Figure 8.1

. When he went to China its social development was far ahead of the West’s.

Figure 8.1. A shrinking gap in a shrinking world: trade, travel, and turbulent times bring East and West together again

There were three big things, though, that Marco did not know when he marveled at the East. First, its lead was shrinking, from almost twelve points on the index of social development in 1100 to less than six in 1500. Second, the scenario foreseen at the end of

Chapter 7

—-that Eastern ironmasters and mill owners would begin an industrial revolution, unleashing the power of fossil fuels—had not come to pass. Marco admired the “black stone” that burned in Chinese hearths, but he admired China’s fat fish and translucent porcelain just as much. The land he described, for all its marvels, remained a traditional economy. And third, the fact that Marco was there at all was a sign of things to come. Europeans were on the move. In 1492 another Italian, Christopher Columbus, would land in the Americas, even if he remained convinced until his dying day that he had reached China, and in 1513 Columbus’s cousin Rafael Perestrello would correct the family’s confusion by becoming the first European who actually did sail to China.